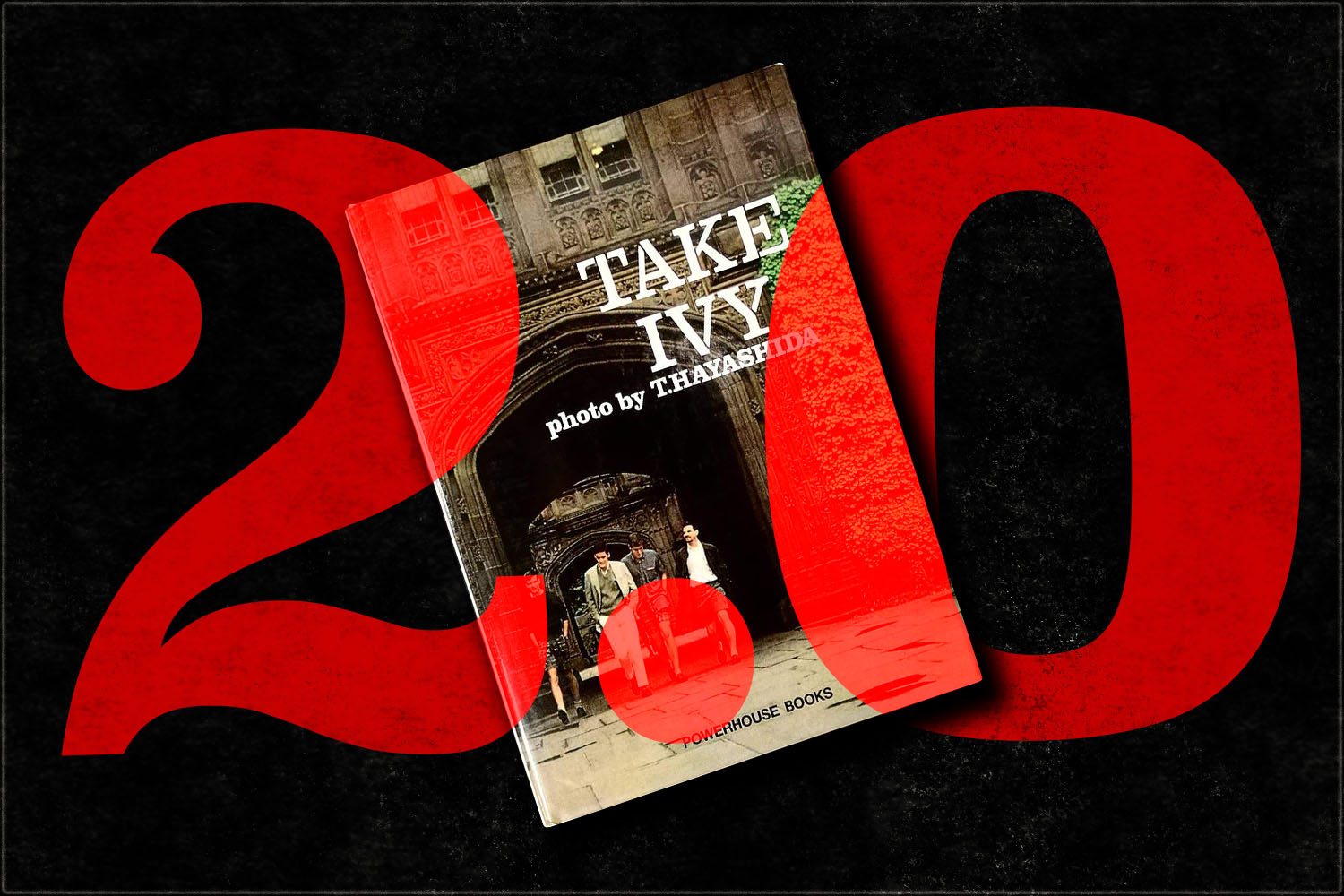

Ivy Style, which broke free of elite East Coast campuses thanks to a photography book shot by a group of style-obsessed Japanese guys, then was eventually mass-marketed by a Jewish guy named Ralph Lauren, stopped being strictly for WASPs a long time ago. That’s why it’s so strange that it took so long for a book like Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style, to come out.

In the book, menswear critic Jason Jules and designer Graham Marsh set out to show that Black people from all over the world have played just as important a part in not only keeping prep style alive, but advancing it. The beautiful volume features shots of Miles Davis, Malcolm X and Gordon Parks, but you also see everyday Black men in the South and Midwest protesting for Civil Rights, and always looking damn cool no matter what. It’s a long time coming, but Black Ivy was worth the wait.

Here, Jules shares with InsideHook his reasoning for including a few of the standouts in the book.

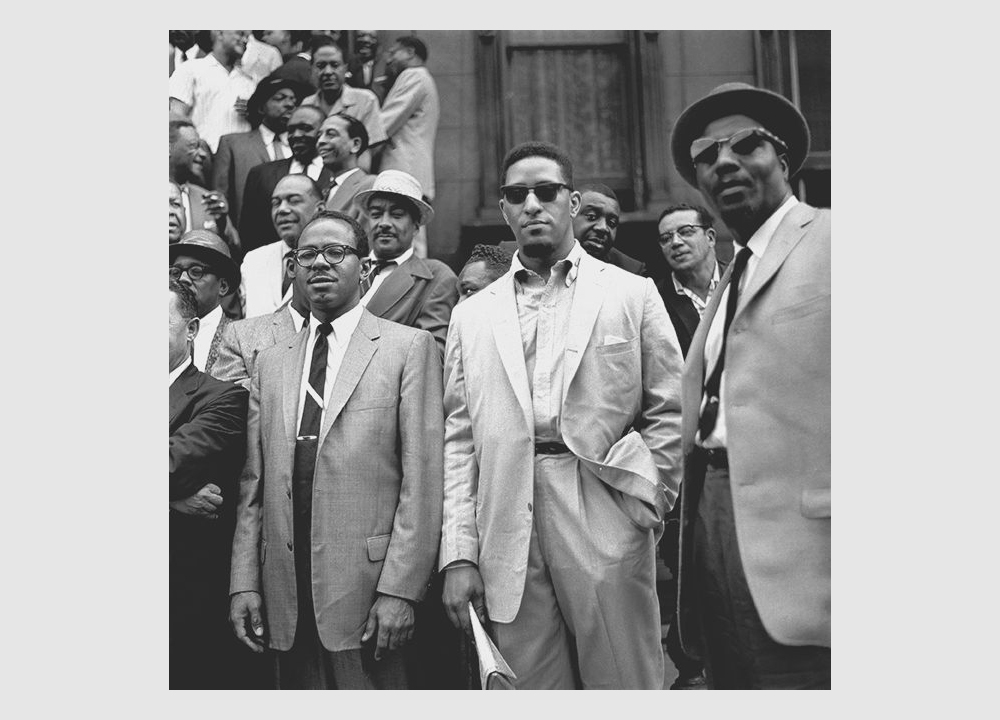

Sonny Rollins by Art Kane

“Obviously, it’s Sonny Rollins. So he’s the definitive modern jazz musician, pushing the boundaries kind of creatively, but also politically as well. So in doing the book, my goal is to kind of show kind of almost like indisputable truths, if you know what I mean, that actually it wasn’t an accident that they were wearing these clothes — which is what a lot of people were trying to say. My argument is that it was a very conscious thing, a deliberate choice, and the clothing reflects the mindset and the mindset being a progressive one. So Sonny wearing these clothes kind of illustrates that to me, especially at that period, especially in that context where he’s surrounded by a lot of his peers and a lot of his predecessors — like some of the incredible greats like Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins are there, Thelonious Monk is there — but then there’s Sonny wearing these clothes. Soft shoulder, the roll on that buttoned-down shirt is ridiculous. It’s amazing.

You can know the story of this shoot, where this guy for Esquire wants to do this story. It’s almost like an impossible story, because these guys are night people. Will any of them turn up? Is there enough of a collective effort for them to turn up? It’s a huge story in the fact that all these guys meet in the same place in Harlem, on this particular morning, and they know they’re having their pictures taken. So they’re not dressed by accident. There’s no casual clothing going on here. So Sonny turns up almost like a statement of intent, if you know what I mean. His mindset is slightly different to everybody else’s, because he is more overtly political, and the clothing reflects that. But it is super-elegant — there’s not a crease there. There’s nothing misplaced. And to me, that’s why it’s so beautiful: that backstory, and also, the image is incredible as well.”

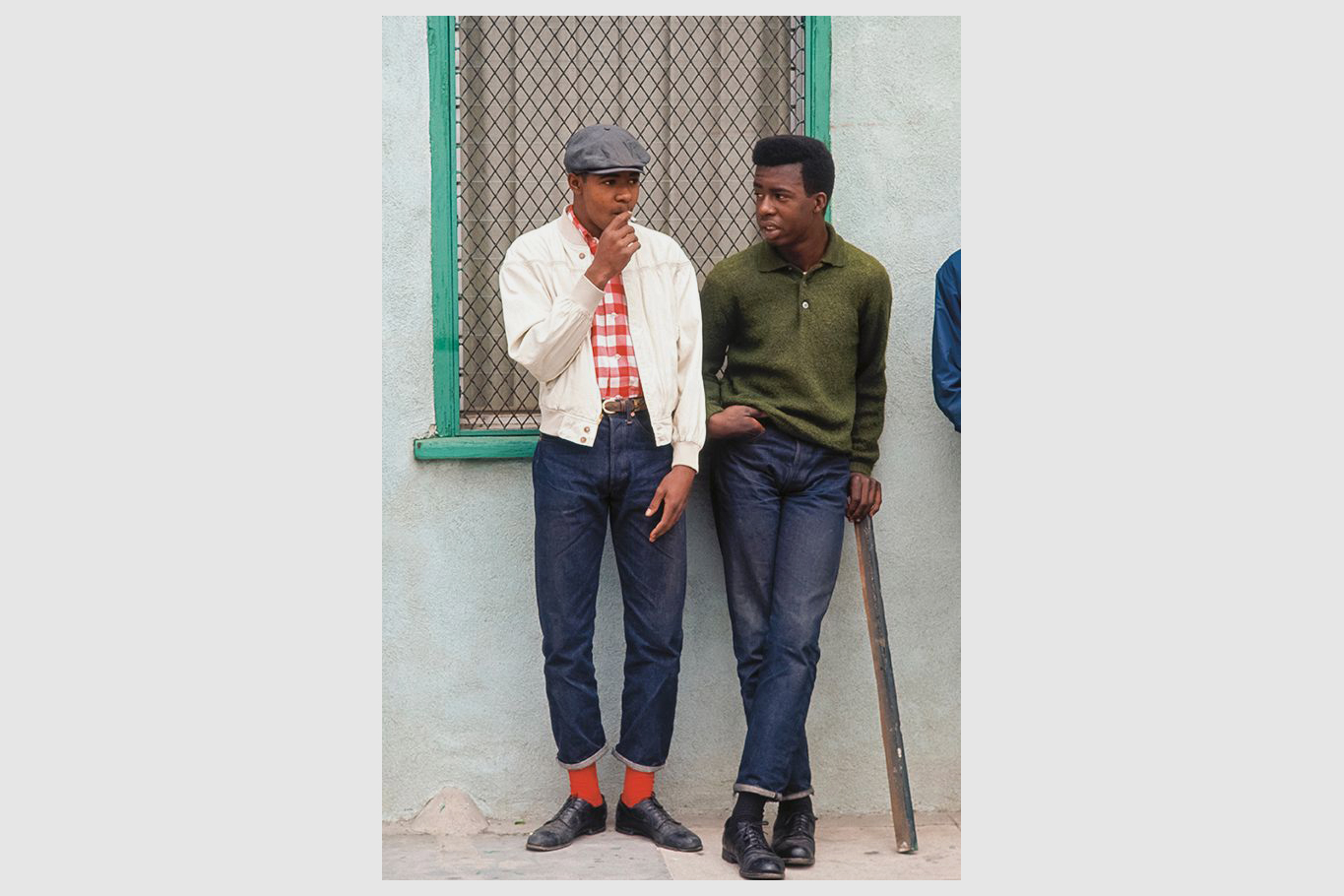

Two guys by Billy Ray for Life

“We have this narrative that Ivy League is this. There are so many reasons for this initiative to be there. The Ivy League is this kind of … white elite. The 1 percent. So all the rest of us are excluded, no matter what color, race, creed, whatever it is, there’s just this small niche of people, and this clothing reflects them. And then you see these guys ambassador-ing their own take on it, but they’re the complete opposite. They’re the outsiders in this story, they’re construed as gang members. So you couldn’t be poles apart from where that world supposedly exists, and yet, they’re wearing these clothes and owning these clothes in a way that actually they have authority over them. They understand that, it’s almost as if they understand how the clothes work within the elite context. They’re redesigning and refining them for their own purposes.

And they’re adding a certain edge and a certain tension. The socks, the shoes, the cardigans — there’s an attitude added to it. And to me, that attitude is actually what makes the whole thing — Ivy League clothing — cool, because otherwise, it would be trad. There’s this energy that’s kind of been invested into Ivy League clothing from people like these guys that has given Ivy League a kind of longevity. But you also need to look at the Mods who started a few years before (this image was taken in ’66 ) in the early ’60s. There’s a strong similarity between the kind of silhouette these guys are using and the guys in the U.K. To me, there’s an impact that guys in Watts who are completely disenfranchised managed to have not only on Ivy League clothing, but also on the European and the U.K. style that we’d later come to call Mod. So to me, it’s a super-important period, and super-important image as well.”

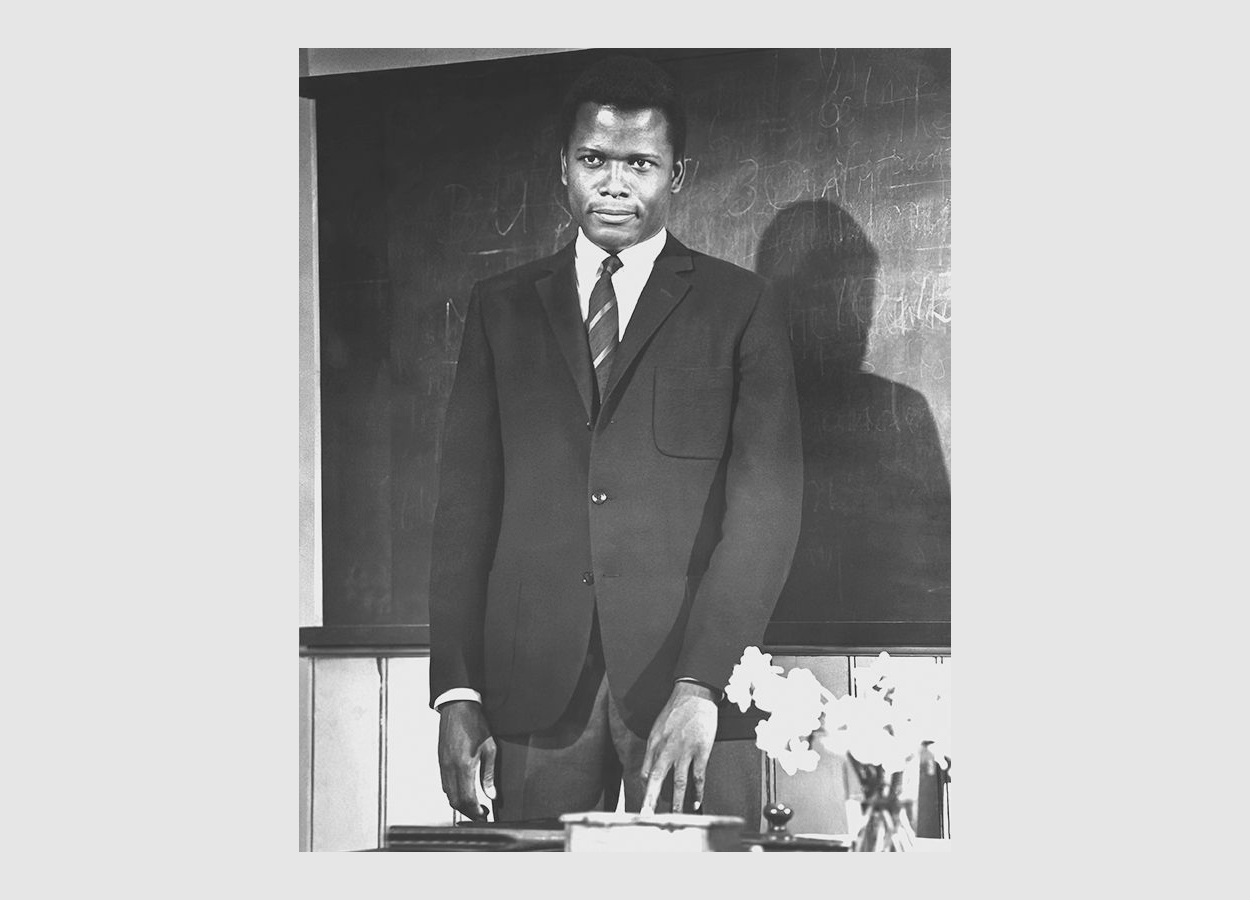

Sidney Poiter in To Sir, With Love

“For me, in To Sir With Love, by wearing the Ivy League uniform, Poitier is the physical embodiment of triumph over adversity. Racially, he’s an outsider, a member of an underclass just like the working-class students he’s employed to teach. As such, I feel that the clothing is an unmistakable way of conveying both to the students and the viewers that he’s somehow managed to break through at least some of the race and class barriers he’s inevitably encountered.

In that way, he presents both metaphorically and literally a way of challenging the status quo. And so he stands as an example for the students to, in their own way, emulate. Maybe it’s not too far-fetched to say that he represents a form of hope or even salvation, much like the real-life civil rights leaders of the time.”

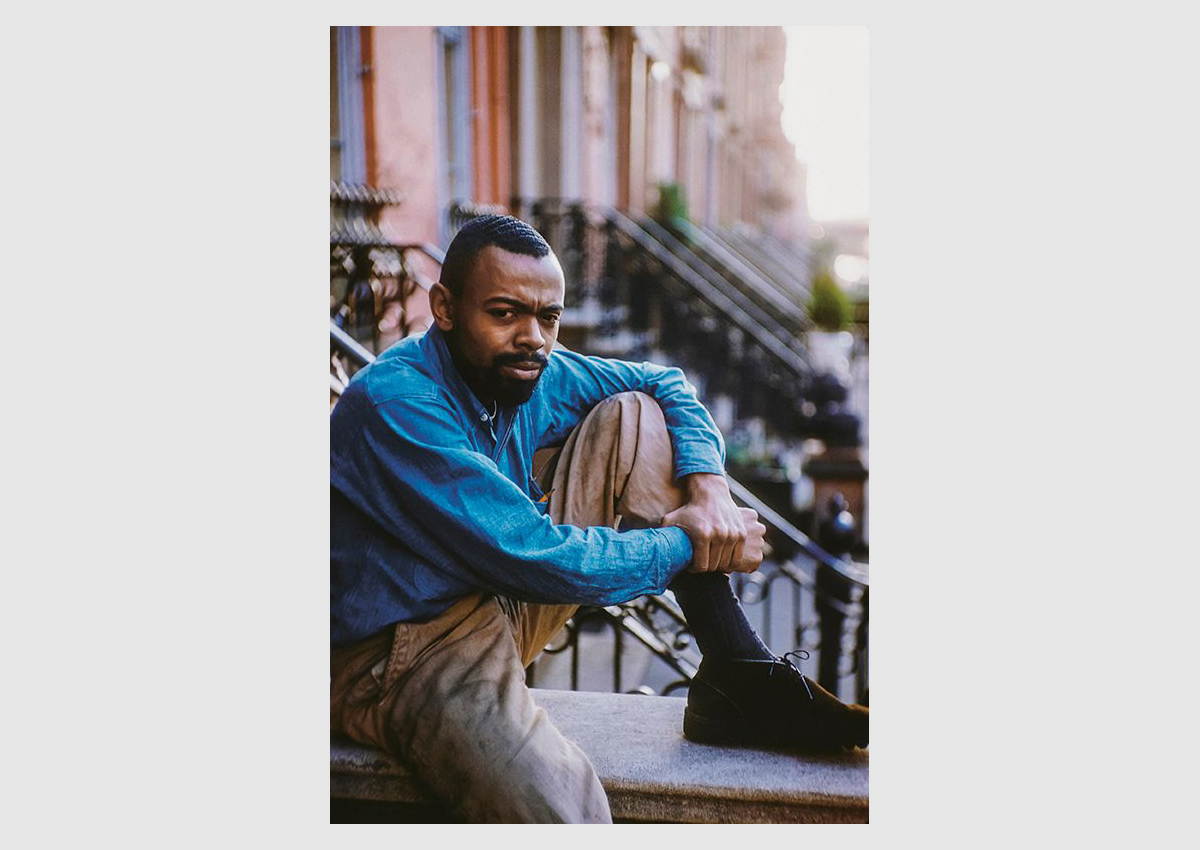

LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka

“He was living then in Greenwich Village, hanging out with the Beats, Allen Ginsberg, etc., but also hanging out with Langston Hughes, who was the generation of poets prior to him. So what you see here is — and no matter what name he adopted or what kind of political theory he approached his work from — he always nailed a look. That’s the thing about Amiri Baraka: When he was wearing his dashikis, he nailed it. When he was wearing his kind of mix of college clothing and the kind of seven-panel hat, he nailed it. In later years, he always knew how to dress. It’s obvious that this is no accident; wearing a chambray shirt with the most messed-up chinos you can imagine is intentional. He’s combining this kind of post-GI style with the chinos with a workwear ethic with the chambray shirt. And then this kind of weird, I guess, beat/jazz thing with the playboy shoes. But it’s all him. It’s all contemporary-modernist Black beat poet.

And to me that’s important — starting off the book with this type of image. There is an Ivy influence and an Ivy kind of lineage here, but it’s not strictly adhered to as we know it, in this kind of purest way. And it never was intended to be. It was always going to be taken and basically kind of ripped apart and then reconstructed, and that’s exactly what [Baraka] has done.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.