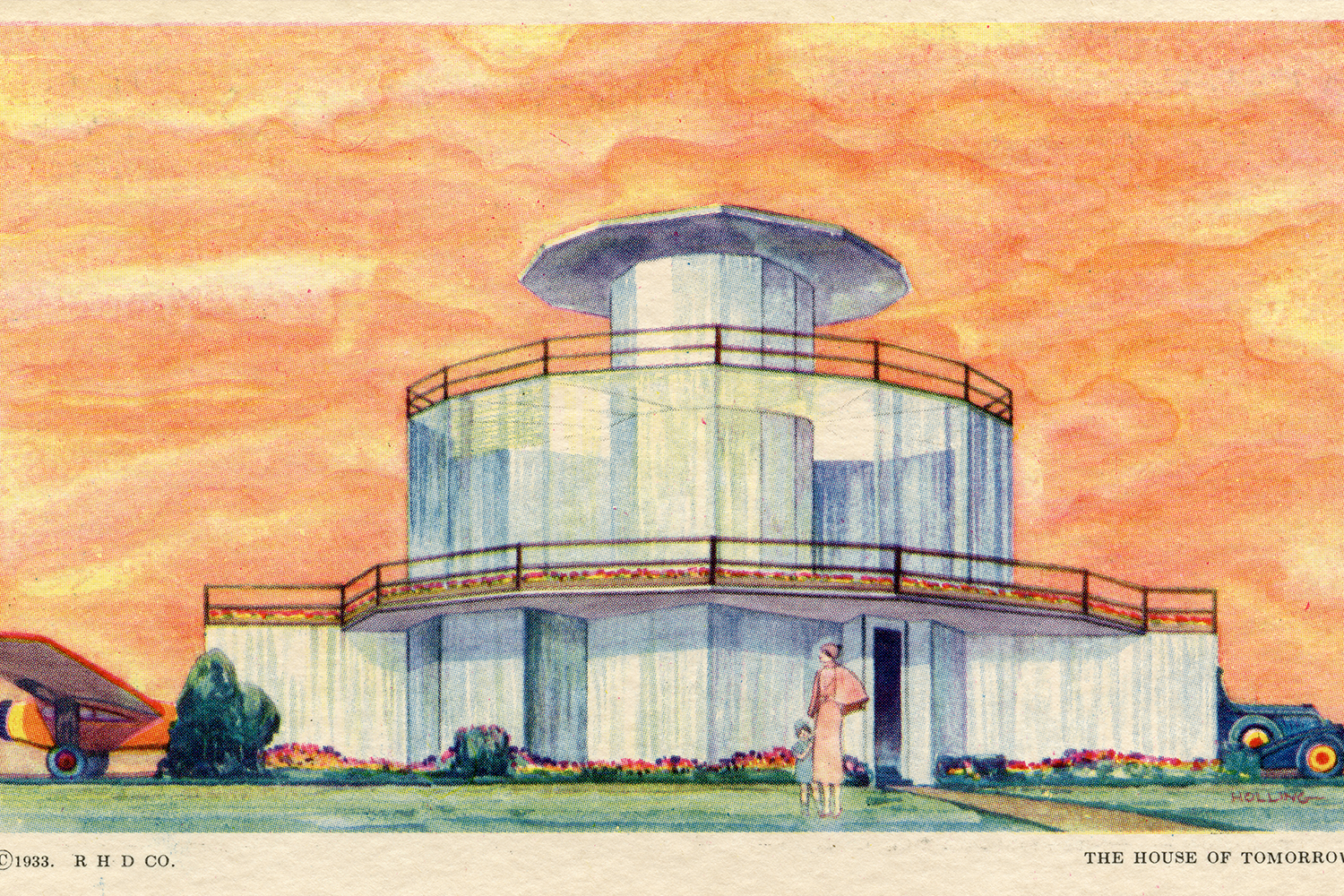

History doesn’t make room for everyone: Plenty of talent slips through the cracks. And even those who’ve enjoyed their time in the sun often find themselves in shadow down the road. Back in the ‘30s, brothers George Fred Keck and William Keck enjoyed the kind of public profile architects dream of. Their House of Tomorrow was the hit of Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition, with more than a million visitors paying an extra ten cents to take a walk through it. Although they went on to design hundreds of homes, the Kecks never enjoyed the enduring fame of Frank Lloyd Wright or Mies van der Rohe, men who are so firmly associated with design in Illinois. But with Houses of Tomorrow: Solar Homes from Keck to Today — on view at the Elmhurst Art Museum through May 29 — the pair are getting another (and very timely) shot at the spotlight.

Born and trained in Wisconsin, Fred Keck opened his Chicago practice in 1927 (William joined him in 1931) and did a decent business designing conventional suburban homes for real estate developers. Long eager to exercise a more modernist approach, both in terms of design and materials, Fred went to town with The House of Tomorrow, creating a twelve-sided, three-story affair of glass and steel spun around a central mechanicals core and outfitted with locally made tubular furniture. While its futuristic appearance and curious amenities (including a hanger for a small plane) captivated fairgoers, the project also set Keck on the road to exploring the possibilities of passive solar heating when he noticed, thanks to his extensive use of glass, how warm the interior became, even in winter.

After the fair, Keck spent years experimenting with various materials and design strategies to perfect his vision of a solar home. Flat rooftops, southern exposures, and eaves measured to mediate the sun’s rays all played a role. Designing a house for real estate developer Howard Sloan, Keck turned to pros at the Adler Planetarium to track the path of the sun for three months so that he could determine the dimensions of the home’s overhangs. “With just the simple notion of using the passive solar idea to save people money on their fuel bill, he was able to build hundreds of homes in the Chicagoland area, many of which are still lived in today,“ notes Sarah Cox, manager of collections and exhibitions at Elmhurst Art Museum. “He even created a formula to help him calculate how much his clients would save on their heating bill if they chose a passive solar home design.”

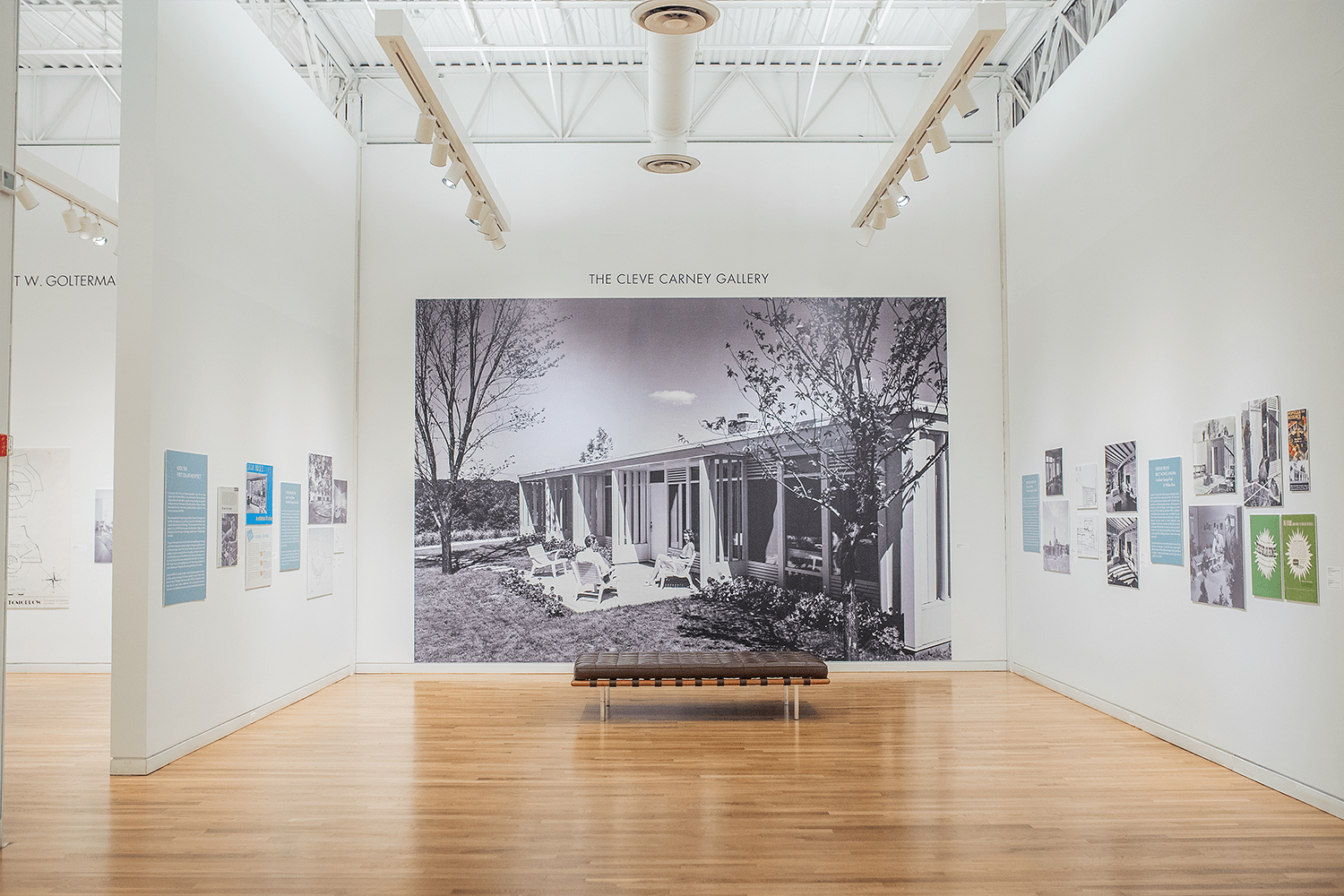

The Elmhurst Art Museum (whose primary permanent exhibition is the Mies-designed Robert McCormick House of 1952) draws from material across the Kecks’ career (Fred died in 1980, William in 1995), using historic photos, architectural artifacts, and design diagrams to chronicle and assess their impact on residential architecture in the area.

The house that started it all still stands, but worse for wear. When the Century of Progress Exposition closed, Chicago developer Robert Bartlett moved The House of Tomorrow (along with several other houses built for the fair) to Beverly Shores, Indiana. It passed through several hands before the National Park Service acquired it in the 1960s. It is currently unoccupied, and Indiana Landmarks is accepting proposals for its restoration as a single-family residence with a 50-year lease.

Many Keck and Keck houses have fared much better. More conventional than The House of Tomorrow, they are excellent examples of Mid Century style — handsomely scaled, warm with wood and brick, and satisfyingly oriented to the landscape. A three-bedroom, three-bath home in Glencoe, where the brothers built a number of houses, sold last summer for $780,000. In a 1940 magazine piece, Fred extolled the virtues of his work — including its passive solar capacity — telling readers that if they earned from forty to fifty dollars a week, they could afford a $5000 Keck and Keck house.

When the price of fossil fuels fell after the Second World War, Keck’s solar card was harder to play. Big cars, new appliances, and more, more, more were the order of the day. And truth be told, the architect’s facility with space and materials were probably as much a selling point as his energy-saving ideas. But as we all wonder how to negotiate a warming planet, Keck looks mighty of-the-moment.

This article was featured in the InsideHook Chicago newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Windy City.