In January 2018, one of the most decorated and popular athletes in Olympic history revealed he had contemplated suicide shortly after winning four gold medals and two silvers at the 2012 Summer Games in London.

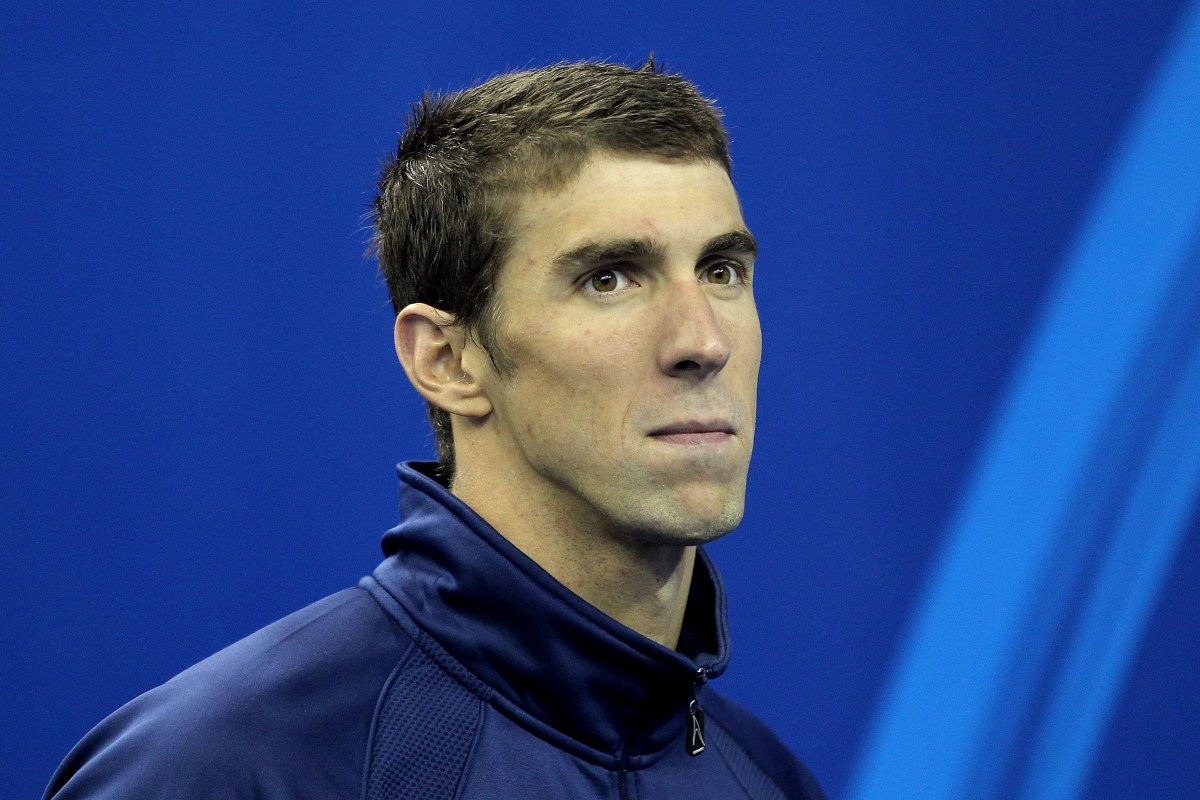

Michael Phelps, who holds the all-time individual record for Olympic gold medals (23), had previously spoken about his struggles with anxiety and depression after his retirement from swimming in 2016, but this was the first time he had spoken publicly about suicide.

“I didn’t want to be in the sport anymore,” he said. “I didn’t want to be alive … You do contemplate suicide.”

Thanks to work he had been doing for a short film about former U.S. bobsled team captain Steven Holcomb, filmmaker Brett Rapkin already knew there was a link between Olympians and depression. Holcomb, who had been competing for the U.S. since 1998, washed down 70 sleeping pills with a bottle of Jack Daniel’s in a 2007 suicide attempt. He survived, though, and later went on to win gold in Vancouver in 2010 and a pair of bronze medals in Sochi in 2014.

Rapkin met with Holcomb to talk about his extraordinary comeback story in late April 2017, about 10 months before the 37-year-old was set to head to South Korea to compete in what would have been his final Olympics. Twelve days after their meeting,Holcomb was found dead in his room at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Lake Placid from an apparent drug and alcohol overdose.

Following Holcomb’s death, Rapkin decided to expand his project by reaching out to Phelps.

“They made me aware that post-Olympic depression, and just depression in general with Olympians, was just a huge issue,” Rapkin tells InsideHook. “So we partnered and started to interview more athletes.”

Those interviews, which were conducted with star athletes like Phelps, Apolo Ohno, Lolo Jones, Shaun White and Bode Miller, are the basis for a new documentary, The Weight of Gold, that debuts tonight on HBO.

While making of the film, Rapkin unraveled a disturbing trend among Olympians: namely, that they tended to “suffer in silence” rather than reveal what they were going through.

“I think they didn’t realize how prevalent the issue was among each other,” he says. “I don’t think it’s something they were encouraged to talk about. I think they needed this platform to talk about it and I’m just grateful we were able to play a small part in providing that.”

In addition to the stigma that publicly talking about mental-health issues can bring, many Olympians had been reticent about discussing their struggles because of the potential professional and financial consequences.

“It’s something that understandably they’ve always been concerned would hurt their standing in the sport or their brand,” Rapkin says.”With the way the U.S. Olympic system is structured and how the finances work, you don’t have athletes signing contracts where they’re making millions of dollars with the team. The income for Olympic athletes has to come from individual sponsorship. Unless they’re able to secure [that], they don’t make any money, even if the team is sponsored.”

With more high-profile athletes — like Phelps and NBA stars Kevin Love and DeMar DeRozan — talking about mental health, hopefully the taboos are starting to dissipate.

“Michael Phelps is definitely a pioneer in this space of athletes sharing about mental health,” Rapkin says. “I think he and some of these other athletes have made it much more acceptable to do so … And I think there is a responsibility for brands like Nike and Ralph Lauren that sponsor the U.S. Olympic team to take a more active role in determining how their funds are delegated. I think everybody needs to make sure the athletes are properly compensated and cared for. Unfortunately, when it comes to mental health, that hasn’t been the case.”

Rapkin is hopeful the release of the film will also pressure the National Governing Bodies (NGBs) that oversee each individual sport to take some sort of action to help combat post-Olympic depression.

“I have to believe they’re all aware of this issue and, if they weren’t before, then the film certainly should make that abundantly clear,” he says. “I imagine there’s going to be a lot more awareness of this issue. These organizations have no excuse not to be aware of it if they weren’t before. It’s their responsibility to work with the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee to come up with a plan and solutions to provide the athletes with adequate resources.”

In addition to helping Olympians, Rapkin wants everyday people to reap some benefits from the film.

“Just as we say in the film, ‘It’s okay not to be okay.’ There’s no reason not to get help and reach out and start a conversation,” he says. “If you’re dealing with mental-health challenges, whether it’s mild depression or feeling suicidal, there’s help out there. It starts with reaching out to someone you trust or one of these many valuable resources that are available, like the Crisis Text Line (Text HOME to 741741) to get help. We also created a website along with HBO — Weight of Gold Resources — where people can go and learn about different resources that are available, whether they’re an Olympian or Joe Six-Pack.”

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.