Artist Eve Werner has a profound connection to the natural environment of Northern California — and to Paradise, the small Sierras town burnt to ashes in 2018. Eighty-five people died as the Camp Fire complex of fires tore through Butte County on November 8, 150,000 acres burned and scores of homes were lost.

Werner spent much of her childhood in one of them.

“I grew up in a different era, when kids got kicked out in the morning — and except for lunch and dinner, we had free reign,” says Werner from her home in Chico. “We could just go wherever we wanted. We’d be horseback riding in the chaparral, swimming, hiking to bizarrely hard-to-find swimming holes. I was always very engaged with that landscape.”

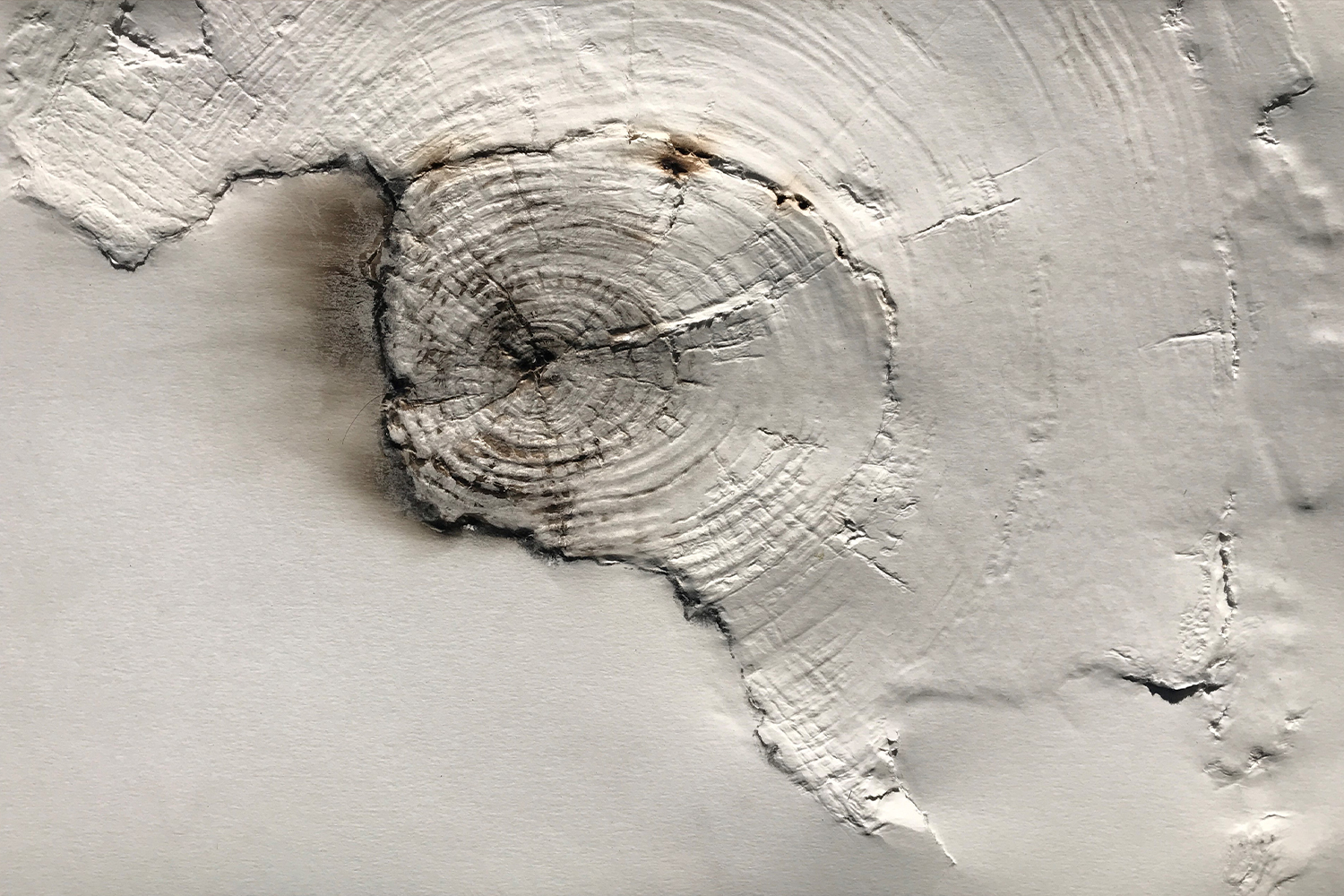

Once primarily a painter of California’s unique natural environment, Werner changed focus after the Camp Fire to create politically charged, mournful works-on-paper and installations, like a ghostly Sierras cabin silent except for a soundscape that sounds like a mash-up of the Dresden fires and the Langoliers. Werner’s rubbings — of dead trees and ruined streets — serve as textural obituaries for lost things, whether made by nature or man.

Here, we talk to the artist and practicing landscape architect about the California wilderness she loves — and the catastrophes to come.

InsideHook: What did you find when you went up to Paradise for the first time after the fire?

Ever Werner: It was impossible to ignore the human destruction. I knew people who actually were lost in the fire. That was too much to deal with at first, so I went to where I felt comfortable. I spent a lot of time making rubbings of trees that died, and of the streets — streets in the part of town that I’d left, where just four houses survived.

What did you find there?

It looked like a bomb went off. Paradise was not a rich town, and so there were many, many trailer parks with maybe 200 trailers. It wasn’t just rubble but rubble that had been tossed into the air — metal twisted into massive piles, at least before the cleanup crews got there. It felt apocalyptic.

I’ve noticed that you’re always sure to describe the fire as anthropogenic. [Blame for the fire fell on outdated Pacific Gas & Electric power lines; the utility company pleaded guilty to 84 counts of involuntary manslaughter in 2020.] Is that important to you in a way it wouldn’t have been if lightning had caused the fire?

I want to keep saying that because there’s so many people — particularly in very conservative places like Paradise — who don’t accept what they don’t understand. And they’re saying that it’s PG&E’s fault, which it was. But even with so-called “naturally” caused fires, the storms causing that lightning are getting worse and more frequent with climate change. It’s important to peel back these layers and understand the true causes.

How did the fire change your artwork?

It’s totally different. I’d been focusing on painting native California trees for a decade or two — and I had been painting them as living things. California has a lot of trees that are endemic here, which don’t grow anywhere else. I’d been focusing on those trees, which are the backbone of many different ecological niches.

Then there was the fire, and I started interpreting it through those losses [of California flora] as a stand-in for the bigger, more universal losses of climate change. And it wasn’t just trees. Thousands of animals died. They weren’t burned — they just died from lack of oxygen while they were fleeing. The fire really was a wake up call for me because I had been very aware of climate change as an extremely serious issue. But until then, I thought we had more time. We don’t. It’s here now. It’s not theory.

What’s so precious about California trees for you?

Where I live now, in Chico, the dominant species is the valley oak. They’re the biggest of all the California oaks — 100 feet tall and 100 feet wide. They define the entire valley floor’s original ecology. There’s literally thousands of species that are dependent on them. I think of them as the backbone off of which all the other wildlife hangs. They’re not drought tolerant, but they live in this incredibly dry climate. We get no rain, usually, from May to October or November. Valley oaks require really deep, wonderful soil and groundwater. But humans have planted all these orchards, and they’re sucking out all the groundwater — so the oaks are slowly dying, and the effects on all the other wildlife is potentially calamitous.

Another tree I love is the bristle-cone pine. It’s not endemic just here, but it’s like an island that only occurs on these mountaintops, and it’s basically immortal. It’s killed by lightning. There are living trees in these forests that are over 5,000 years old — which is essentially the beginning of human civilization; they’ve been there the whole time. And now they’re threatened as the climate gets warmer. They only survive forever because it’s so harsh where they live that there’s very little microbial life and no competition from other trees. As it warms, the conditions are allowing more microbes and more trees, which might include a faster grower that can out-compete them.

Your older tree paintings felt very celebratory to me, but in this new work I feel like there’s just so much despair. Where is the emotional register of these works for you?

This environment that I love will be drastically altered in my lifetime. I would say I fluctuate between wistful — and wanting to be immersed in as much of it as I can — and feeling doomed.

Do you feel like the hairs on your arm stand up as we get closer to fire season?

Yeah. I feel like I’m carrying a backpack.

Are you really? Like a go bag?

Oh, no. I know people who do. I do feel this impending sense of doom. All winter long it didn’t rain, and everything’s just completely dried out. We had our first wildfire two weeks ago. It’s only burned a couple of hundred acres, but it’s like — to have wildfires on the first of May, it’s just our reality now.

Is there much crossover in your work as an artist and as a landscape architect?

In some ways. I’ve worked with a number of people up in Paradise, and their number-one goal is to have the house look like it used to. It can’t. It was what’s called yellow pine forest — Ponderosa pine. These people lived in heavily forested areas of town, and now they have no trees at all. I had one client who had 50 big pine trees, and now she has none. She liked it with the trees. She’s 75. She will never see a tree that’s more than 10 feet tall on her property again.

We’re discouraging people now from having any trees around their house. And we live in a place where it’s frequently over 100 degrees. Not having trees is brutal. But people get it.

What do you think the future of Paradise is?

It’ll burn down again. I lived there for only seven years as a child, but my family lived there for another eight years after I left, and there were no fires in Paradise the whole time. For the decade or two decades afterwards, if there were fires, they were infrequent.

But since 2020, there have probably been 10 fires. I have one client up there with a still-standing house, and three times everything around her has burned. Paradise is situated on a ridge, surrounded on two sides by these canyons that have strong winds, and what’s growing back is mixed with very flammable, non-native grasses.

So yeah, it’s going to burn again. I feel like an asshole saying that, because people are really hoping it’ll never burn again, but it’s like, look at where it is. It is just going to keep burning.

This article was featured in the InsideHook SF newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Bay Area.