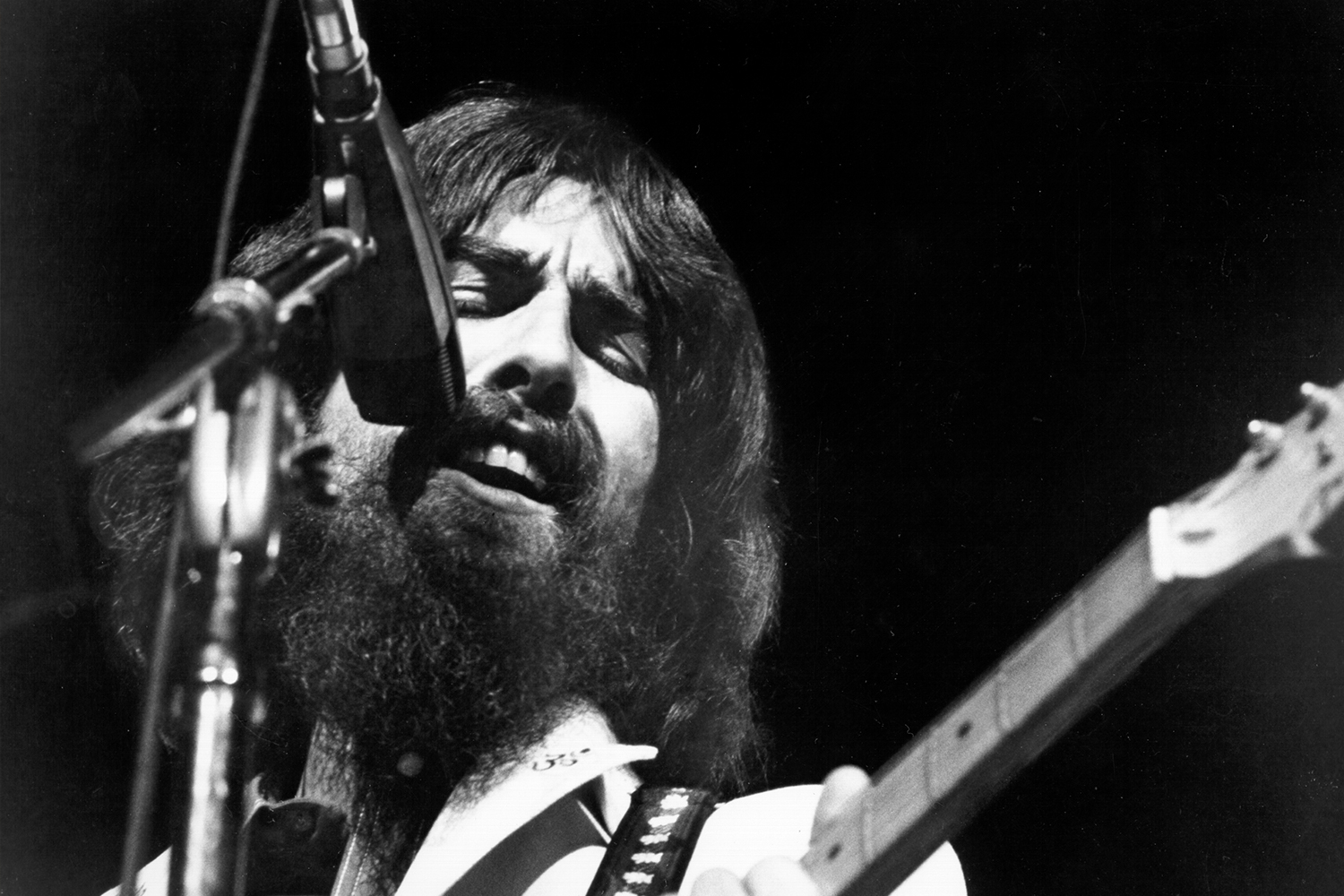

“Everyone calling George the ‘Quiet One’ and all that was always so silly to me,” Klaus Voormann, George Harrison’s friend since the Beatles’ Hamburg days recalled last year. “He was anything but quiet. He was actually quite loud, when I think about it, and very funny and sarcastic, but also very thoughtful and serious. He could get angry, as well, but was, of course, very spiritual. He was really so very many things.”

All of those many facets of Harrison’s unique personality are on full display on the new 50th anniversary expanded edition of All Things Must Pass, the triple album released in the immediate aftermath of the breakup of the Beatles, which announced Harrison as a solo creative force to be reckoned with.

The newly revamped version — all 23 tracks of it — has been lovingly remixed by Harrison’s son Dhani alongside Paul Hicks, whose recent credits include reissues by the Beatles, John Lennon and the Rolling Stones, and it includes 47 additional tracks, including solo acoustic demos, stripped-down early versions of some of Harrison’s most famous songs, works in progress and even a handful of songs previously unreleased in official form. It’s being released as a 5-CD set that includes a gorgeous 5.1 mix of the album, an astonishing sounding 8-LP vinyl edition, and a $1,000 “uber” edition that includes several books and even a bookmark made from a fallen tree at Harrison’s beloved Friar Park estate.

“George had so many songs,” Ringo Starr, who appears on the album and collaborated with Harrison frequently after the breakup of the band that made them both household names right up until Harrison’s death in 2001, recalled in 2018. “He’d play them for us, just him on an acoustic guitar, so we could learn them, and each one was better than the previous one.”

Harrison had dabbled in solo pursuits before All Things Must Pass, of course. He’d released Wonderwall Music, a soundtrack album for the film of the same name, which featured Starr and pal Eric Clapton, among others, in 1968, and his Moog synthesizer noodlings were released as Electronic Music in 1969. Even some of his contributions to the Beatles — “Within You, Without You,” “The Inner Light” — were essentially solo songs. But in the wake of his breakout success as a songwriting force on the Beatles swan song Abbey Road in late 1969 (“Something,” from the album, was his first Beatles A-side, and “Here Comes the Sun” is still one of Harrison’s best-loved songs, by far the Beatles’ most-streamed song), Harrison began flexing his creative muscle in new and remarkable ways. He became the de facto talent scout for the Beatles’ new Apple Records label, producing Badfinger, friend Billy Preston and Doris Troy and scoring a No. 1 U.K. hit with the “Hare Krishna Mantra” single by the Radha Krsna Temple, the London outpost of the Hare Krishnas, of whom Harrison often joked he was an “honorary devotee.”

But perhaps most importantly, on a whim, Harrison joined Clapton and former Traffic bandmember Dave Mason in the backing band of Delaney & Bonnie & Friends on tour in the U.K. and Europe just before Christmas of that year.

“There was a song called ‘Comin’ Home,’ that had a slide guitar part,” Mason recalled in 2015. “It was simple, but he took it and made it his own. Later on he told me that was the start of his love of playing the slide guitar.”

It became Harrison’s signature sound — a mournful but lyrical extension of both his singing voice and spiritual yearning — and appears on songs peppered throughout All Things Must Pass, most especially the No. 1 worldwide smash “My Sweet Lord.”

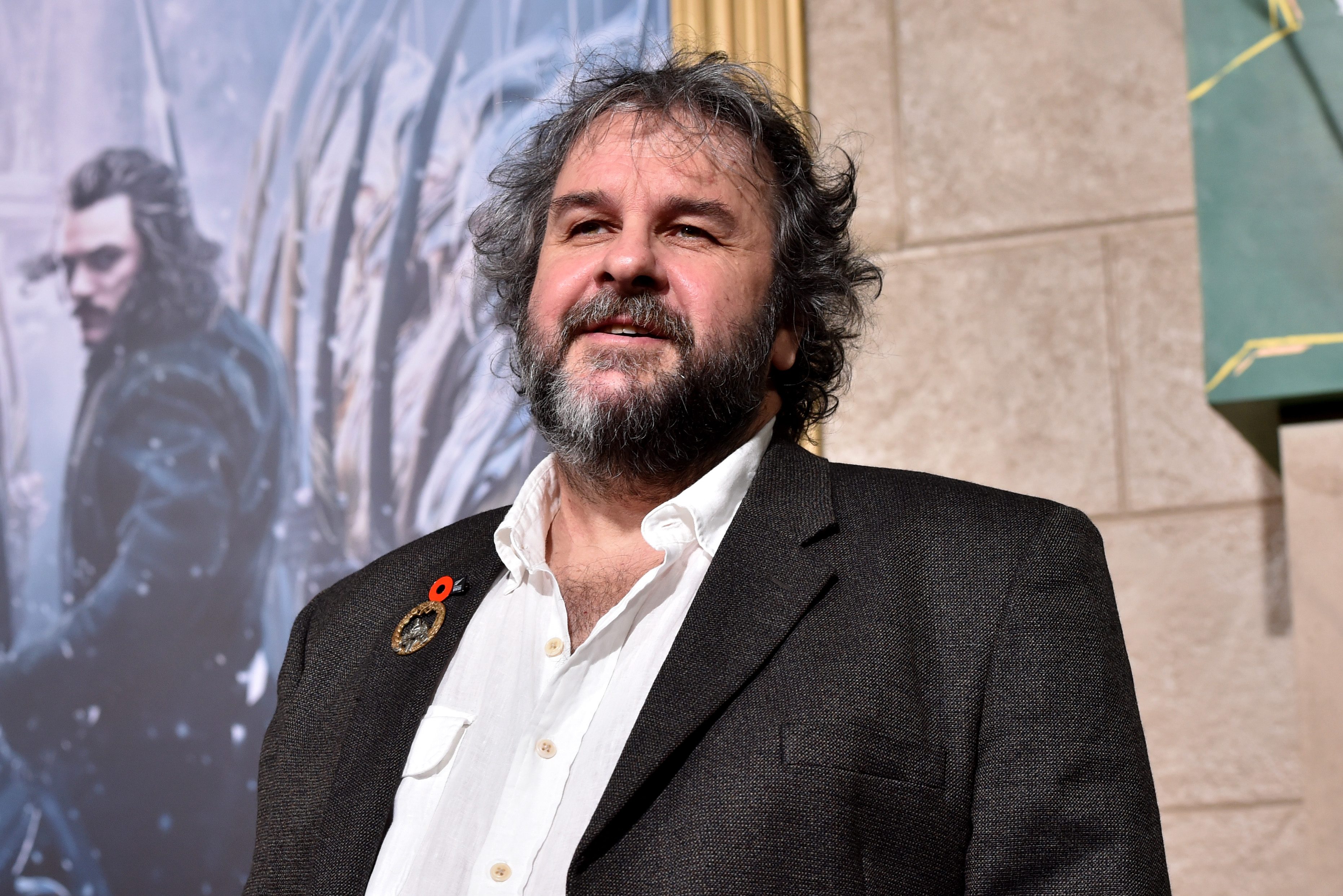

“That slide sound is George to me,” Peter Frampton, who also appeared on the album, recalled in 2019. “For one of the truly great guitarists, George is often overlooked. But all of those Beatles songs, there isn’t anybody who doesn’t know the parts George contributed to them by heart. But his slide playing, that was him setting himself apart as a player. No one else can play quite like that, and you immediately know it’s George when you hear it.”

Playing with Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, a group of Southern gospel rockers — the core of which would go on to form Derek & the Dominoes with Clapton — supported by some of Harrison’s friends from London’s music scene who were steeped in R&B and the blues, just on the heels of working with Preston and Troy (and coupled with Harrison’s own search for a meaning in life beyond the endless trappings his unfathomable success had given him) imbued the songs he was working on at the time, many of which would find their way onto All Things Must Pass, with a soulfulness unlike just about any of his white contemporaries.

“George was a deep guy,” Starr recalled of his dear friend. “He was funny and could be tough and all that, but he was serious about finding meaning in life.”

In fact, more than one of the songs on All Things Must Pass, including “My Sweet Lord,” began life inspired by “Oh Happy Day” by the Edwin Hawkins Singers, a massive hit at the time, filtered through Harrison’s own unique take on spirituality.

“George had a lot of questions,” Voormann recalled of Harrison’s never-ending search for “God consciousness,” as the former Beatle put it. “I lived with him for about three years [beginning] around the time he was making All Things Must Pass, when the Beatles were breaking up and his mother was dying and his father was ill, and he was juggling all of that. We would stroll around the garden at Friar Park, and he would marvel at the trees and the flowers and everything; things I would have barely noticed otherwise. He was always searching [for ways] to get closer to God.”

As for the other major inspiration in the grooves of All Things Must Pass, The Band, whom Harrison had visited at Thanksgiving in Woodstock in 1968 just as the Beatles began to disintegrate, were of course no slouches when it came to laying down deep, soulful grooves, and Harrison returned to England and the sessions in early 1969 that would become Let It Be singing their praises to his bandmates.

But it was Bob Dylan, who often wrote about spiritual matters — and even later went through his own “God conscious” moment — who was the other major inspiration for Harrison at the time.

The pair wrote several songs with and for each other that appear on All Things Must Pass (and more included in the bonus tracks) and Harrison also included Dylan’s “If Not For You” on the album, which Dylan had written for his New Morning album. After years of being treated as a junior partner in the Beatles by Lennon and McCartney, to be treated as an equal by the undisputed king of songwriters was just the thing Harrison needed to stiffen his resolve as he set out on a solo career.

“George liked being in a band,” Ken Scott, who was an engineer on All Things Must Pass recalled. “He wasn’t a front guy. That just wasn’t his nature. But I’m sure having had those hits and being taken seriously by Eric Clapton and Dylan and Phil Spector helped him get over any fears he had.”

While the new edition of All Things Must Pass doesn’t strip back as much of Spector’s fabled “Wall of Sound” — much of which was printed onto the original multi-track tapes — it does give depth and clarity to many of the individual instruments previously buried in the mix, and most especially Harrison’s voice.

While it was Spector who acted as foil and ringleader for Harrison in the early days of the making of All Things Must Pass, after two months of work he returned to Los Angeles to tend to ill health attributed to copious alcohol consumption. Harrison then set about overdubbing guitar parts and backing vocals, before Spector returned to help put the finishing touches on Harrison’s magnum opus, though not before writing lengthy production notes to Harrison, urging him to spend more time on getting things just right — most especially his vocals.

“I really feel that your voice has got to be heard throughout the album so that the greatness of the songs can really come through,” Spector implored.

Harrison heeded his erstwhile producer’s words, and the proof is especially evident on the new remix of the album, still regarded as one of the — if not the — best of the former Beatles’ solo works. Upon its release, Ben Gerson of Rolling Stone referred to All Things Must Pass as the “War And Peace of rock and roll,” calling Harrison’s songs and Spector’s production “Wagnerian, Brucknerian, the music of mountain tops and vast horizons.” In 2021, with George Harrison now gone nearly 20 years, the newly spiffed-up edition of All Things Must Pass reminds us that it stands as great as ever — as remarkable, powerful and penetrating as any rock and roll ever recorded.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.