Maybe it was its unusual speed that made the Russian traffic police pull over the hearse. This was not a normal mournful pace, and what the authorities found when they insisted the driver open the coffin was far from expected. There the police uncovered 500kg of illegal caviar, valued then in 2015, at around $2 million.

It’s not just the look of caviar that wins it the nickname of “black gold,” but its value as well. Some four ounces of quality caviar is worth roughly the equivalent of an ounce of the precious metal. Such was the potential money in its production that Ayatollah Khomeini — who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 to 1989 — approved the reclassification of sturgeon as a scaled fish so it could be handled by devout Muslims working in the country’s fledgling caviar industry.

Caviar’s rarity has ensured it retains its status as one of those luxury foods that, regardless of how appetizing it may be in reality, is fetishised by the wealthy. But an estimated two-thirds of the U.S. population has never tried caviar. “When asked what the best way to enjoy caviar was, my father once said, ‘when somebody else is paying for it,’” laughs Peter Rebeiz, CEO of Caviar House & Prunier, one of the oldest established importers of caviar.

Traditionally, the caviar industry has been problematic. Even though international trade of wild sturgeon has been banned since 2006, the number of wild sturgeon — the slow growing, slow reproducing fish from which this roe has traditionally been harvested — has been brought to near extinction level. And it’s all the more disturbing given the incredible nature of sturgeon: they are one of the oldest fish in existence, with fossil records dating back 200 million years. Native to the Caspian Sea, each fish can grow up to 15 feet long and weigh 240 pounds, with some living for close to a century, which has earned them the nickname Methuselah of freshwater fish.

In 2010, beluga sturgeon, among the most highly-prized of the many species, was classified as “critically endangered” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, a situation which has not improved much since. And it’s not alone: the 27 sturgeon species are designated critically endangered at a higher percentage than any other species assessed by the organization, including mammals, reptiles, amphibians and plants. The black market in wild caviar from the Caspian countries — not helped by a messy geo-political situation in the region — is still thought to outstrip the legal trade by 10 to one.

But the last two decades have seen the slow ascent of an altogether better alternative, at least for the survival of the species: caviar from farmed sturgeon. This market has exploded. Ninety percent of the world’s wild caviar once came from sturgeon overfished in the Caspian, but it’s now being farmed in the UK, Paraguay, Spain, Israel, Saudi Arabia and California, among other places. China is the world’s biggest producer, responsible for a quarter of global output.

But this too is not without its challenges, not least in convincing chefs and consumers that caviar from farmed sturgeon is comparable to the wild variety — much like the stark difference between wild and farmed salmon is sometimes a bone of contention for bon viveurs. Yet recent advances are producing farmed roe that is comparable in taste and texture. Farmed caviar is nuttier and creamier (while wild has more salinity), and it even has what is known in the trade as the “Caspian pop” in the mouth, a characteristic that softer, farmed roe had initially lost.

“It took a lot of convincing to get chefs to take farmed caviar,” says Ramin Rohgar, managing director of Imperial Caviar, one of the earliest importers and distributors of caviar from Iran. “It was more expensive than the wild kind, and the quality wasn’t there. Today, chefs will tell you that the quality is every bit as good. Now the problem is more that the ignorance of some consumers means a struggle to convince them to take caviar from China. They don’t mind that their iPhone is made in China, but they assume caviar production there is all about cutting corners. But then, there’s always been an element of snobbery about caviar.”

Joseph Yoon Would Like You to Consider Incorporating Bugs Into Your Diet

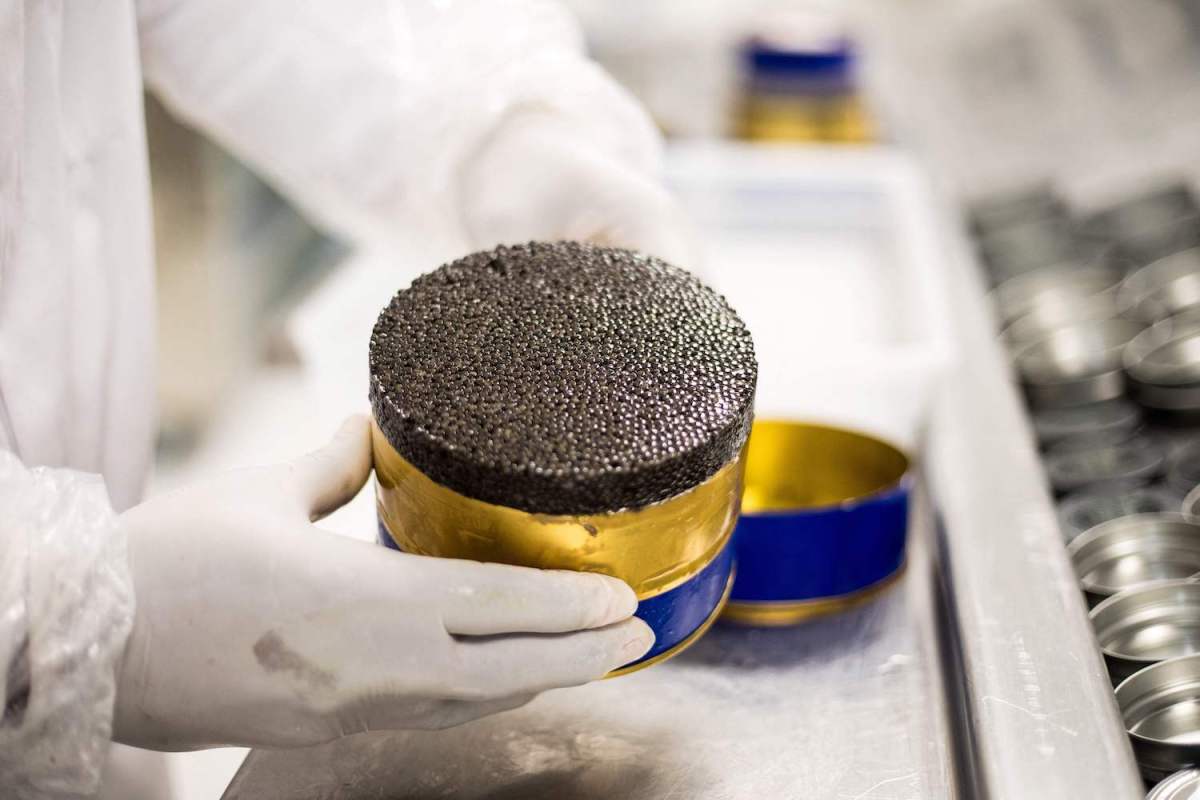

The first episode of “Gastro Obscura: Sparked” explores the misunderstood world of edible insectsMonitoring the fish is now a hi-tech affair. Caviar House & Prunier is one of the companies to introduce ultrasound scanners, similar to those used to monitor human pregnancy, to better assess both the fish’s health and the ideal time for harvesting its eggs, while other systems employ implanted microchips. Water quality, temperature and lighting all need to be carefully controlled. Roe is quickly washed, dried, packed in salt and left to rest for a month (or many months for a stronger flavor). It’s then repacked in tins for sale.

The means by which farms harvest the sturgeons’ eggs — a somewhat opaque, confusing and sensitive subject — is sometimes met with skepticism within the trade and is a reflection of the increasingly intense competition within it. They can inject an artificial hormone that promotes egg release and stuns the fish, followed by a process called “stripping” to remove the two ovaries and extract the eggs though a small incision. Or they can make a larger cesarean section to remove the eggs then stitch the fish up, which, if it survives, allows the fish to continue to produce roe. But, some claim this procedure causes stress — because at this stage some 80% of the fish by volume is eggs — and stress can impair the caviar’s flavor.

Removing roe from the fish entails one of these methods, and the constant, expensive battle of replenishing one’s farmed fish stock is always top of mind. As a saying goes, it takes eight years to produce one kilo of caviar (roughly the time it takes for a Siberian sturgeon to become sexually mature; Beluga take an economically impractical 20 years), eight months to get caviar from the fish (the reproduction cycle) and about eight seconds to eat a tin of it. So much is being done by the industry to maximize production efficiency.

“I think we have to draw a distinction between sustainable methods and ethical ones,” Rohgar says. “Farms are sustainable in that they’re not taking sturgeon from the sea — they’re essentially enclosed environments, working with many generations of fish. But ethical? I don’t think the incision method is ethical. For me, ethical is allowing the fish to live in good water, with the time, care, space and nutrition they need and in an environment as close to natural as possible — maybe in outdoor lakes, which environmental standards allow in some countries — and then quickly killing the fish when it’s time to remove the eggs. Of course, some would argue that the purely ethical move is not to remove the eggs at all.”

New ideas keep coming, too. A more complex and as yet not commercially proven method of removing the eggs is by “milking,” or massage: physically working the farmed fish in much the same way as it rubs itself up against rocks in the wild to trigger egg release. But sturgeon’s prehistoric physiology — unlike that of salmon or trout – doesn’t lend itself to this method. It also only works with an experimental means of stopping the chemical process that prevents the eggs from coagulating on release into water, as they do in the wild. Because the eggs are captured in a way that is close to natural, the theory is that farmed fish are encouraged to produce a greater volume of eggs year over year. But the naysayers argue the eggs collected this way are too soft.

“I do hope these kinds of methods will work one day, but those who say that they already do are lying,” Rebeiz says. “Either the sturgeon does not survive, or because you’re removing the roe before it’s mature, you can’t say it’s really caviar. The fact is that [the caviar industry has seen] a lot of people playing around with terms like ‘ethical,’ ‘bio,’ ‘green’ and so on. There are a lot of people launching farms because they think they can make a lot of money but have no idea what caviar should taste like. They’re like new winemakers who’ve never had a drink. Making caviar is a very high-investment, very long-term process. You need to be in the business for the love of the product.”

Indeed, farming may pose a bigger problem. Since the early 2000s, global caviar production has increased almost four-fold to around 400 tons. That may still be considerably less than what was being produced from fisheries with wild sturgeon 40 years ago, but a rapid growth trajectory is to be expected, though Rebeiz expects many of the newer players won’t go the distance. How can a product whose cachet is founded on its rarity cope with increased production levels, if budget caviar is something anyone wants? And won’t that just create greater demand for the wild kind?

“It’s going to be interesting to see what happens if the market reaches saturation,” says Phaedra Doukakis-Leslie, ex-academic director of marine conservation at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and now fishery policy analyst at the U.S. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. “But what’s more concerning is that there is definitely still illegal wild sturgeon fishing going on, with consumers in many regions likely not knowing or caring. I think the idea that you can take farmed caviar and use it to just replace wild caviar without any effort is questionable. There’s still work at the community level to be done to stop poaching and save these species.”

Every Thursday, our resident experts see to it that you’re up to date on the latest from the world of drinks. Trend reports, bottle reviews, cocktail recipes and more. Sign up for THE SPILL now.