When Sofia Coppola was a teenager, she and her father, Francis Ford Coppola, cowrote Life Without Zoe, a 40-minute short that the elder Coppola directed for the 1989 anthology film New York Stories. The Zoe of the title is a high-spirited, spoiled, charming girl who lives more or less alone in a luxury hotel — like Eloise, who lived on the “tippy-top floor” of the Plaza, though Zoe is around the corner at the Sherry-Netherland — where the butlers, doormen and security guards attend to her like the little mice and birds who dress Cinderella. (Unlike Cinderella, Zoe favors Chanel. Sofia Coppola, 17 at the time of the film’s release, is credited as the costume designer.) Zoe’s father, played by Italian cinema heartthrob Giancarlo Giannini, is “the greatest flute player in the world,” but though he dotes on his bambina when he’s around, he must often fly off to the ancient capitals of Europe, where he is lauded and laureled for his art. She dreams that someday, when she’s older, she’ll accompany him on tour, book all the hotels and order the room service.

Whether or not you’re tempted to read anything autobiographical into this story of the shared but separate solitude of a famous father and the fashionista daughter who only sees him between engagements, Sofia Coppola’s films as a director return again and again to the kind of hotels where such a daughter might conceivably have visited such a father on one of his press junkets, as a treat: the Park Hyatt Tokyo of Lost in Translation, the Chateau Marmont of Somewhere, the Carlyle, up Fifth Avenue from the Sherry-Netherland, of A Very Murray Christmas and On the Rocks. Luxurious but transient, these spaces are tailor-made for the kind of men who populate the films: remote men, beloved but weary, usually jet-setting artists. Their essential melancholy, quite often, bonds them to young women, who are equally introspective, emotionally restless and tentative in their dissatisfaction. Sometimes the relationship between the older man and younger woman is implicitly paternal, sometimes literally so.

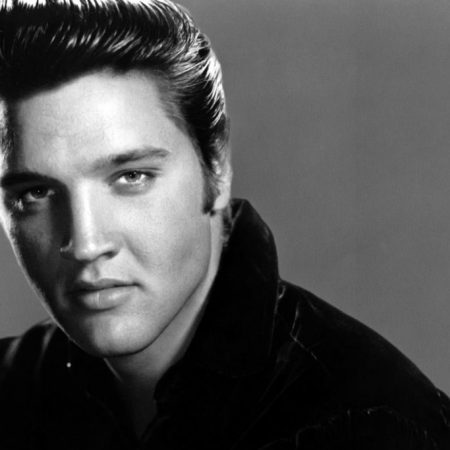

Coppola’s new Priscilla is based upon Elvis and Me, Priscilla Presley’s memoir of the superstar she met at 14, when he was 24 and the most famous person in the world, and eventually married. The film is on the one hand a familiar Sofia Coppola picture, moving through a gauzy, glamorous, basically hollow doll’s house, in this case Graceland, in a teenage-dream haze. But on the other hand it breaks new ground for her: This time, the pairing of the starry-eyed princess in the tower and the sad king (or, indeed, The King) is a sexual one, and all the more discomfiting for it. While still understanding of the gravitational force through which older and more powerful men might seem to validate an unformed person’s yearning for something more, something rapturous, the film is more sharply ambivalent about age-gap and power-imbalanced relationships. And because Daddy, in this case, is the man who invented American pop culture as we know it, Priscilla reckons with the continuing implications of patriarchal fawning, of the cult of genius, of the nostalgia we still live with.

Priscilla opens with painted toenails on deep pile carpet — possibly a reference to the opening credits of Kubrick’s Lolita — before setting the scene in West Germany, 1959, during Elvis’s military service, when one of his friends spots Army brat Priscilla (Cailee Spaeny) at the soda fountain and invites her to a party at the King’s. Priscilla’s mother and stepfather are uncertain, but stepdad knows the officer that Elvis’s panderer serves under — the military chain of command neutralizes, or legitimizes, any potential exploitation.

At the party, Elvis (Jacob Elordi) plays a Jerry Lee Lewis song at the piano, but Coppola is on to a more subtle kind of predation than Dennis Quaid seducing Winona Ryder in Great Balls of Fire! Elvis tells Priscilla to wait for him in the bedroom, so they’re not seen going upstairs together, but mostly he just wants to talk about what the kids are listening to back home in America. Elvis’s house in Germany, where his friends and family seem to have gathered to accompany him during his sojourn abroad, is another of Coppola’s pleasant liminal worlds, where the tinkling of glasses is muffled by the thick carpets. It’s all a bit of a dream for Priscilla, who coming back into her bedroom after dates can only throw herself back on a pink bedspread and let out a heavy, besotted sigh.

When Elvis’s hitch is up and he and Priscilla part at the airport, she loses sight of him in a mob of screaming fans as soon as he gets out of the taxi — out of the bubble, Coppola begins to make clear, Priscilla has a private claim on a very public person. The score by Thomas Mars incorporates “Love Me Tender” as she pines for him in Germany — only once Elvis is out of her life, seemingly forever, does Priscilla start acting like a moony teenybopper, reading magazines and pinning up posters. So it is very much a fan’s fantasy when Elvis calls, a couple years later, and asks to bring her to Graceland. He assures Priscilla’s parents that she’ll be looked after there, where his father and grandmother live, like one of the family — the nuclear unit, like the Army, vouches for him as he takes over her life.

You can see where it’s all going, especially if you know anything about Elvis’s eventual descent into addiction and mania, but it takes a while to get there. At first, Elvis seems as much a spectator to fame as Priscilla does — at the movies, he mouths all of Humphrey Bogart’s lines in Beat the Devil, and he speaks to her of his ambitions and his insecurities as an aspiring actor. Cailee Spaeny and Jacob Elordi were born a month apart, in the summer of 1997, but they recreate an asymmetrical dynamic in other ways. At six feet, five inches tall, Elordi looms over his costar; he’s a charming actor but has also developed a way of throwing his lines away, letting them spill out of his mouth almost self-effacingly, disappearing into the mist that surrounds him up there. This Elvis, like the real one, worships Marlon Brando, but his halting vulnerability is more magisterial than it appears — his air of distractedness and cautious spontaneity is appealing, even sympathetic, but the audience, like the five-foot-one Spaeny, senses that his attention is elsewhere, and she has to fight the whole movie to regain it. Getting ready to get into bed with Elvis, she brushes her hair and puts on perfume, but he just wants to take a pill and go to sleep, and gives her one as well. She wakes up slowly, gently, beatific as Sleeping Beauty, to discover that she’s been out for two days.

Eventually, the Brando mumble turns into paranoid rambling on the phone. Elvis’s reliance on uppers and downers is a bit Walk Hard-y, but Coppola is judicious about balancing the wild good times against a souring sense of excess, as Elvis and Priscilla and the Memphis Mafia, his posse of enablers, go from closing down the theme park for the night and riding the bumper cars, to flipping over golf carts, to taking a bulldozer to Graceland’s outbuildings.

Elvis travels frequently, always bringing the Memphis Mafia on the road with him while insisting Priscilla — underage and a danger to his public image, as well as a hindrance to his womanizing, or his good times with the boys, or both — stay home. In many ways, it’s a typical midcentury marriage; Elvis’s many larger-than-life episodes, his religious and gun-crazy phases, are grounded by Spaeny’s inquiring, absorbing performance, and Coppola applies a light touch even to scenes of Elvis Presley giving his child bride amphetamines to help her finish her exams and bringing a gun to her high school graduation.

Coppola does not challenge Priscilla’s claim, made in Elvis and Me, that she was a virgin when she married Elvis, nearly eight years after meeting him and four after moving to Graceland permanently — Elordi’s Elvis bears little trace of the world-shaking pelvic urgency that Austin Butler and Baz Luhrmann brought to Elvis last year. He’s softer, weighed down by his waning artistic relevancy as the Beatles overtake him — by the time Priscilla met Elvis, he was already a nostalgia act, relegated to cheesy movies and self-plagiarizing cash-in soundtracks — and his dominance takes a correspondingly softer form, as soft as the faux-fur bathroom scale on which Priscilla continues to weigh herself well into her pregnancy. He picks Priscilla’s hair color — jet black — and takes her shopping, giving a thumbs-up or thumbs-down to the outfits she tries on, like Jimmy Stewart in Vertigo, remaking Kim Novak in the image of his obsession.

The overbearing male presence in a makeover scene stings especially in a Sofia Coppola film. At the Q&A session following Priscilla’s New York Film Festival press screening, Cailee Spaeny said that many of the choices in her performance were, in essence, made for her by the wardrobe and hair and makeup departments — sometimes her hairpiece was so big and heavy, her makeup so thick, that it dictated how Priscilla would carry herself, a bit classical in her stillness and a bit boxed in. Priscilla puts on her false eyelashes after her water breaks and before the drive to the hospital, and when she emerges, baby Lisa Marie in arms, Spaeny’s wig is about twice as big as her head.

I Hope Austin Butler Keeps Talking Like Elvis Forever

The actor’s vocal coach recently weighed in on the accent that just won’t go awayPriscilla’s journey is very much a hair and makeup story — by the 1970s, shortly before her divorce, her palette has shifted to incorporate more nude shades, for a natural look, and she’s stopped dying her hair. Meanwhile Elvis is in Vegas, wrapped up in his own demons, getting kitschier by the minute in jumpsuits and capes. (We seem him perform only fleetingly, from behind, as if watching from backstage. The audience is out of focus in front of him, like the angry crowd Kirsten Dunst acknowledges at the end of Marie Antoinette.)

Coppola is interested deeply in artifice, particularly its feminine form. Priscilla’s beauty rituals have the effect of making her look like someone else’s idea of womanhood — maybe her boyfriend’s other, more age-appropriate girlfriends, like Ann-Margaret and Nancy Sinatra, whom she only ever reads about in the movie magazines. It’s almost as if one of the high-school girls from The Bling Ring has broken into a star’s home, started trying on her clothes, and then gotten herself locked in her closet.

The extravagant textures of Coppola’s films, her interest in style, classifies her as a director of what in Classical Hollywood were called “women’s pictures,” and she’s a master of women’s spaces as well — the domestic interiors to which they are often confined, in classic melodrama as in her films. (Her focus on well-appointed closed spaces is partly a function of budgetary constraints: Shooting largely in a single soundstage over the space of about a month, Coppola didn’t have the resources to stage concerts with screaming extras representing the famed “50,000,000 Elvis fans.” So, her film remains strictly “behind the music,” in multiple senses.) In Graceland, Elvis and Priscilla stay in their bedroom while the maids drop off their meals on trays outside the door — room service, like in the Sherry-Netherland, or Chateau Marmont, or Park Hyatt Tokyo, or the Carlyle. But Elvis even more than the best flute player in the world belongs to everyone, and Priscilla, waiting for her husband on Graceland’s long cream-colored couch, begins to seem like Scarlett Johansson’s bored young bride in Lost in Translation, all dolled up with no place to go, sitting by herself in the lap of luxury. Think also of the Lisbon sisters, in The Virgin Suicides, cooped up in their repressive family hothouse; or of Marie Antoinette, kept well apart from the turmoil of history in the palace at Versailles, the most lavish of all Coppola’s cloisters, where she moved, like Priscilla, to marry a man she first met at 14.

Like Marie Antoinette, Priscilla opens with an anachronistic needle-drop: “Baby I Love You,” by the Ramones, a cover of the Ronettes song. Many of the songs on Priscilla’s soundtrack are similarly somewhere along the postpunk-shoegaze continuum, echoes of the bubblegum ’50s in which Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound slowly breaks apart into a swirl of druggy reverb, as in the faraway rocker “How You Satisfy Me,” by Peter Kember of Spacemen 3’s Spectrum project. It calls to mind a 2017 piece for Film Comment about the music Twin Peaks, in which the critic Nick Pinkerton described the echo and reverb of Julee Cruise and Angelo Badalamenti’s “Falling” as congruent to David Lynch’s overall project: “’50s Americana rendered as it resounded across the space of years.”

In her falsies and bouffant, Spaeny here looks not unlike Lana Del Rey (and in turn Lana’s plump fillers and all-American aura of spaced-out decadence are pure Elvis). Coppola, who has impeccable taste, curates an aesthetic unified more by vibe than by era, rendering the moods and yearnings of the past that “resound across the space of years” and persist into the present — including in the form of idol worship of men who are maybe monstrous, maybe tormented, maybe just lost (in translation or otherwise). By tracking the haunting resounding of post-WWII youth culture, and doing so through the lens of a relationship that we — if not necessarily Priscilla Presley herself — would now characterize as grooming, Coppola ponders the use of a Great Man of History to a present day that’s far more anxious about the license such men are given.

But the thing is, old affections die hard, and the film, wistful from the outset, is more sad than angry. Early on in the film, while Elvis is out on tour, Priscilla walks out through the back door of Graceland to find a present he arranged to leave for her: a puppy to keep her company in his absence, waiting for her inside a tiny white picket fence. She plays with the dog inside her own fence, along the boundary of Graceland — but not too close, as she’s warned, because she’s supposed to be a secret from the world.

There’s a story about playing by yourself on your side of the fence in Life Without Zoe, too. Zoe has befriended a new kid at school who has lots of toys but no one to play with. But she tells him: “Whenever I’m lonely and have no friends, I just have a lot of fun by myself, and people always peek over the fence and say, ‘Can we play too?’” (The story cheers him up, and the two go shopping together.) The tragedy here is that Priscilla can only ever have fun by herself, away from any of the eyes that might peek over the fence and see her.

Still, I can’t help but remember that later on in Life Without Zoe, in a sequence at a fancy children’s costume party, that same poor little rich boy dresses up as… Elvis. Coppola’s films invariably save a bit of tender love for all those difficult older men, as this Priscilla does for Elvis. The song playing as Priscilla finally spreads her wings and flies away — written by a major female artist, in gratitude towards the former mentor whose fame she soon outstripped — is unmistakably sentimental, even as it sees her out into the great big world, through the flung-open gates of Graceland and past the throngs of fans still hoping for a minute inside her gilded cage.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.