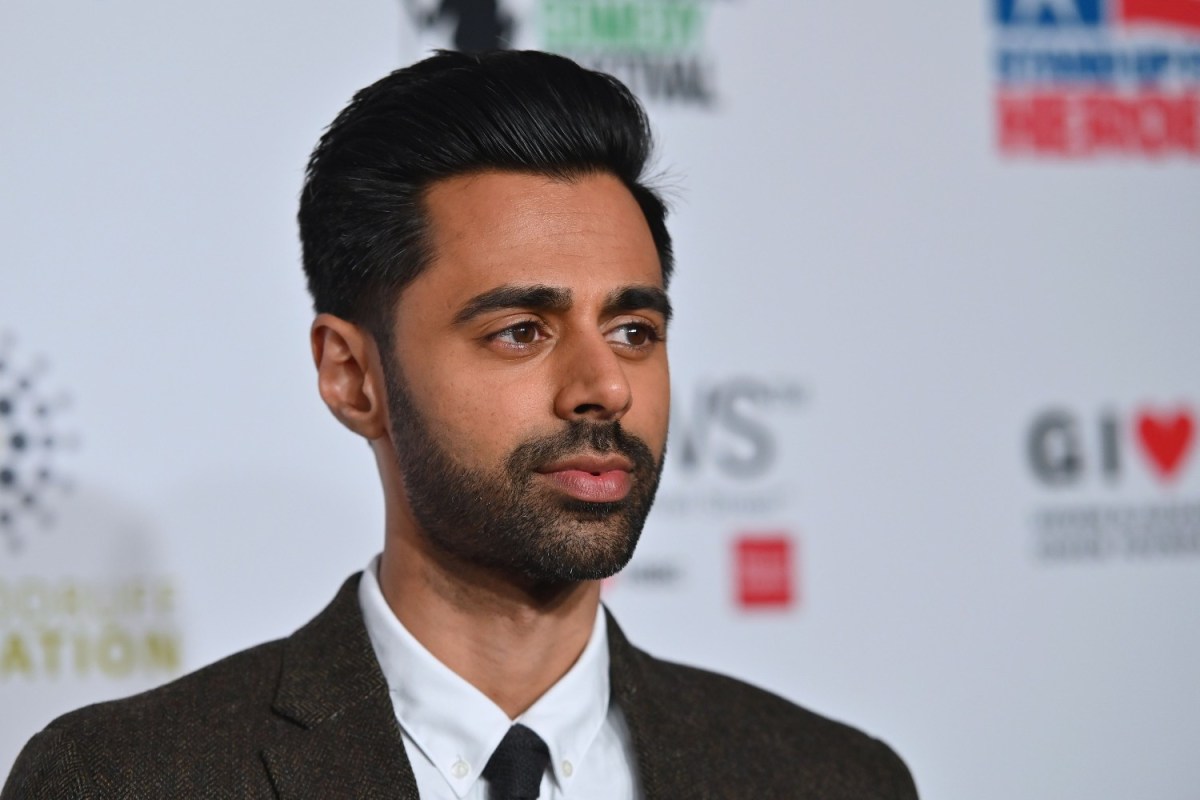

This week, discussion of a popular comedian opened the door to a much larger debate over audience’s relationships with people who tell jokes for a living — and what each side owes the other in that relationship. The inciting incident was the publication of Clare Malone’s profile of Hasan Minhaj in The New Yorker — specifically, whether or not some of Minhaj’s onstage anecdotes about his life were not, strictly speaking, true.

“[A]fter many weeks of trying, I had been unable to confirm some of the stories that he had told onstage,” Malone writes — and Minhaj confirms that, as she phrases it, “many of the anecdotes he related in his Netflix specials were untrue.” Much of Malone’s article is dedicated to the gray areas that arise from this — ones that Minhaj seems to be aware of, given that he makes a distinction between his standup work and his role as the host of the Netflix show Patriot Act.

Some of the reactions to the profile recalled the controversy a decade ago when Mike Daisey came under fire for making claims in a monologue that didn’t hold up to fact-checking. Others took it more in stride; the novelist Tananarive Due commented on Twitter, “I always assume that comedians use a seed of truth and then exaggerate.” Due went on to note that some comedians — Anthony Jeselnik in particular — are clearly playing fast and loose with the truth, to memorable comic effect.

Still, it represents the latest iteration of an ongoing debate about what comedians owe their audiences — and what those audiences should expect in return.

Minhaj isn’t the only comedian to build much of their routine around themselves — or, at least, a version of themselves. To cite a few examples: John Mulaney, Ali Wong and Patton Oswalt have all memorably referenced their own lives in their work. (More on the first of those names in a bit.) But there’s no rule saying that you have to get personal; Jim Gaffigan’s bit about Hot Pockets does not require you to know anything about Jim Gaffigan’s life. And the same is true for comedians who tap into the absurd — think Maria Bamford, Steven Wright and Julio Torres.

Still, there’s a long tradition of comedy deriving both humor and power for the way it overlaps with its author’s lived experience. And it’s hard to watch, say, Jerrod Carmichael’s Rothaniel without becoming at least somewhat invested in the life of Jerrod Carmichael — or at least the version of it he’s presenting to the audience on stage.

I brought up Mulaney before in part because the last few years have served as a valuable lesson in the degree to which audiences’ parasocial relationships with comedians can turn troubling. Many of Mulaney’s material focused on his relationship to his now ex-wife Anna Marie Tendler and his sobriety; when Mulaney and Tendler announced their divorce and Mulaney entered rehab, it left a lot of people unsettled.

Streetwear’s New Muse Is…’90s Comedians?

Bryan Cranston stars in Kith’s newest campaign — and he’s not the firstHere’s the thing, though: maybe it shouldn’t have. Mulaney’s latest special, Baby J, finds him riffing on those very fractured parasocial relationships throughout the night. After telling one especially harrowing story of relapsing into addiction, Mulaney pauses. Then he says something that’s both very funny and a reminder that the version of Mulaney’s life he’s telling the audience is not, actually, the full story of his life: “As you process and digest how obnoxious, wasteful and unlikable that story is, just remember — that’s one I’m willing to tell you.“

That said, the line between the longform monologues of the aforementioned Mike Daisey and the late Spalding Gray and the world of standup comedy is increasingly blurred — Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette comes to mind as a work that inhabits a space between those traditions, as does Chris Gethard’s Career Suicide. But it’s also not like any form of nonfiction isn’t subject to some ambiguity over what is and is not real — consider the (highly recommended) books of Ryszard Kapuściński, or filmmaker Werner Herzog’s concept of “ecstatic truth.”

The most intriguing part of Malone’s article may well be when she describes a bit Minhaj did about a high school crush of his — one which led to the women in question being doxxed when fans of Minhaj sussed out her identity. Here, there’s a case to be made for less veracity in the telling of a story making a larger impact; here, there’s a case to be made for making the same point while using fewer identifying details.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.