You finally encounter an animal that has fascinated you all your life.

You realize the photos, the videos and even the stuffed specimens have utterly failed to prepare you for the real thing: It’s been worth every single one of the tens of thousands of dollars—actually, when all your expenses are added in, hundreds of thousands of dollars—you spent to get to this moment.

Then you kill it.

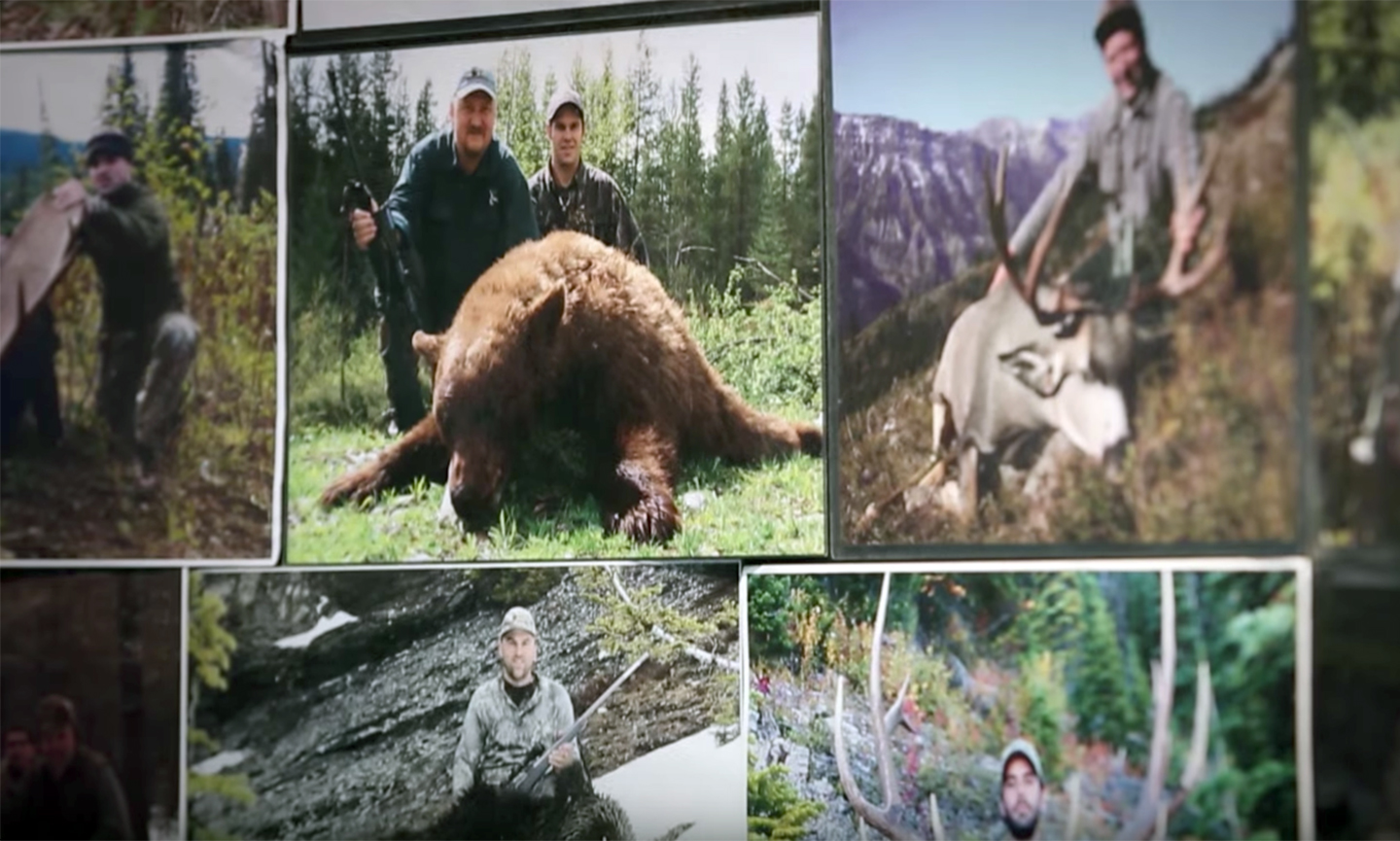

Shaul Schwarz (2013’s Narco Cultura) and Christina Clusiau’s new documentary explores the world of trophy hunting, where the rights to kill a single rhino may be auctioned off for $350,000. By Clusiau’s own account, they initially set out to shame these hunters.

“We realized it’s not so black and white,” she told RealClearLife.

In a perfect world, many people (including both filmmakers) would prefer for rare animals like lions and elephants to be left alone to live out their lives in the wild.

But what happens as people close in on their natural environment (particularly when these people may be struggling to survive themselves)?

“When human and wildlife meet, there’s a problem,” Schwarz said.

On some occasions, the solution seems to be trophy hunting.

Ideally, trophy hunting allows for a small quota of animals (most likely older ones) to be auctioned off to wealthy hunters. This can generate significant money for locals while minimizing the number of outsiders—even tourists carrying cameras instead of guns can do a lot of damage.

Trophy hunting provides an economic incentive for people to protect their animals. As Schwarz put it: “If there’s a poacher in the area shooting an elephant, they’ll feel like the poacher’s stealing from their community.”

In economic terms, this is all coldly logical. But for those who remember learning a Minnesota dentist had killed Cecil the Lion, it’s more complicated.

Indeed, even now Schwarz describes this type of hunting as “kind of psychotic.” But the pair decided the more important issues are whether it encourages a greater number of animals to be bred and, prior to the hunt, what the animal’s quality of life is. Clusiau said she came to stop worrying about the “psychology of the trophy hunter” and instead focus on the animals themselves. (That said, Trophy viewers will be madly psychoanalyzing a lion hunter who credits his love of hunting to both the bible and his dysfunctional relationship with his father and, upon finally making the kill, bursts into tears.)

By these standards, very unexpected conclusions can be reached.

For instance, Schwarz noted there are animal farms where you can “get drunk” and then “drive a pickup and shoot” at wildebeests. This is appalling both to animal rights activists and many hunters, who find it disgustingly unsporting. Yet Schwarz wonders if it’s really that bad for the animals. He says the wildebeests killed are “likely to be old males.” Yes, they are on a farm, but it’s “fairly big” and they “live a fairly good life.”

“Is that worse than what the cow I ate yesterday went through?” he mused. “I don’t think so.” He was far more appalled by keeping “a lion in a cage just to release him and shoot him,” finding that quality of life so low it made any conservation gains “hard to stomach.”

This isn’t to say trophy hunting magically ensures we save all the animals while providing a great standard of living for the people around them. The filmmakers noted it is necessary to vigilantly make sure places aren’t being overhunted and the revenue generated is actually reaching the community. “God is in the details,” Schwarz said.

Clusiau said trophy hunting is best suited to places that include areas in Namibia and Zimbabwe where “the wildlife is the only way people can make money.”

They also agree that when it comes to rhinos, both hunters and hardcore green activists get it wrong.

Clusiau noted that rhino horn (per weight) is worth “more than heroin or gold.” This has made rhinos a target of poachers. But these killings aren’t just illegal and cruel—they’re financially shortsighted. After all, the horn grows back.

“It’s made out of the same material our nails are,” Schwarz said. He poses the question—how is harvesting rhino horns “different than milking a cow?”

In theory, rhino farms should be more profitable than poaching could ever be, as rhino horns can be harvested again and again. Except that rhino horns are illegal. Meaning instead of legitimate farms, the money instead goes to poachers. (Indeed, Clusiau said that rhino farms are extremely dangerous to operate currently because of the continual threat of poacher attacks, killing both rhinos and staffers who stand in their way of the horns.)

“When it comes to rhino and legalization, I’ve completely flipped,” Schwarz said. “We are silly stubborn and unrealistic—rhinos will go extinct if we don’t legalize the trade in horns.”

Yet this argument has failed to persuade many people: “I’ve heard green organizations say, ‘I’d rather see rhinos go extinct than being bred on farms.’” (To which he responds simply, “I disagree.”)

At the same time, trophy hunters are more determined to kill rhinos than ever, leading to those $350,000 auction fees.

What is the future of trophy hunting? The pair believe it will continue to exist, but they don’t expect it to grow. Clusiau said she felt the numbers will be reduced by “people moving away from rural areas” and leaving hunting behind as well. Schwarz felt it’s a demographic that consisted largely of “older, richer white men,” a group whose numbers “may thin out a bit.”

Whether the hunters or groups with a focus on animal rights ultimately gain the upper hand in the conservation movement, Schwarz said we should find hope in knowing both are ultimately asking the same question:

“How do we make rhinos, lions, elephants and other animals walk around the earth in 10, 20, 100 years?”

Trophy opened Sept. 8 in New York and will make its Los Angeles debut Sept. 15.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.