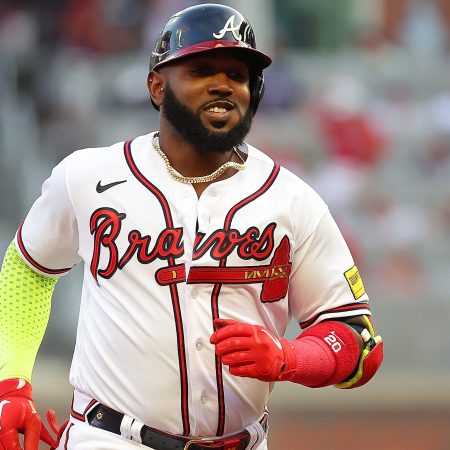

Science and baseball have seemingly always overlapped. Whether it be the trajectory of home run balls or velocity of pitches, baseball’s scientific side has been a mainstay in the game for decades.

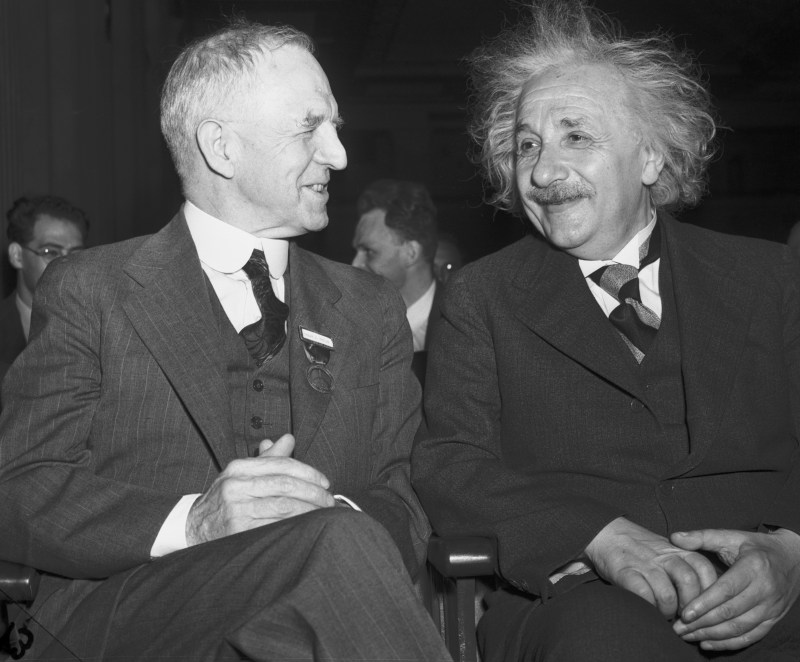

But at one point in history, this wasn’t exactly the case. From baseball’s inception through the mid-1950s, for example, few people believed that curveballs actually “curved,” except for the pitchers throwing them. It wasn’t until ’59 that the naysayers started believing their own eyes. This came about as a result of the research conducted by Lyman Briggs, one of the physicists who worked on the atomic bomb. Briggs applied his understanding of physics to prove how, in the time a baseball traveled the 60 feet and 6 inches from pitcher to batter, it could break up to 17.5 inches. The science didn’t lie.

Learn more the impact of Briggs’ study here, or find out how he proved the curveball curved below. At the bottom, watch a highlight reel of Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Clayton Kershaw throwing some of the best curveballs in the game.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.