The bulk of Allen Funt’s career revolved around his curiosity for reaction. He had a lifelong fixation on creating scenarios and documenting how his subjects responded to their unusual circumstances, but approached what would otherwise be clinical work with a mischievous zeal. He was no methodical researcher and came upon his insights casually, if at all. His earliest gigs, as the mind behind the wackiest stunts on NBC Radio’s Truth or Consequences and a punch-up man for Eleanor Roosevelt on her radio commentaries, hinged on his ability to play the public like a piano. He’d cut out the middleman with his own show in 1947, The Candid Microphone, in which a young Funt pulled a fast one on unsuspecting dupes and a 27-pound mic unit hidden in a park or office captured their flummoxing.

Funt believed he had happened upon a schematic with tremendous potential, and shopped a televised equivalent to ABC in 1948 with the title’s The dropped, Facebook-style. One year later, he crossed town to NBC and tweaked it once more to Candid Camera, which stuck for the next six decades of broadcasts. The show let the tactfully concealed cameras roll as oblivious marks landed in assorted put-ons, from desk drawers mechanically popping open to more elaborate tomfoolery involving Funt’s squadron of actor plants. (Millennial and Gen Z readers: this was the Punk’d of its time, and the one where they pranked then-former President Harry Truman was that era’s Justin Timberlake crying episode.)

As creator and host, Funt masterminded hundreds and hundreds of ruses, leaning on his yen for amateur psychology and sociology more and more as the years went by. Some segments dispensed with the wool-pulling entirely and chronicled revealing interviews between Funt and ordinary folks. He found the peculiarities of homo sapiens endlessly fascinating.

The other thing to know about Allen Funt is that, like many red-blooded Americans, he enjoyed looking at people with their clothes off. It was the marriage of these two great passions — quirks of pathology and full-frontal nudity — that yielded the illuminating historical footnote What Do You Say to a Naked Lady? 50 years ago this month.

By February 1970, X-rated films had fully infiltrated nationwide cineplexes. The public was coming around on the fact that the ignominious rating was not necessarily synonymous with hardcore pornography, and that following April, the previous year’s carnally freewheeling Midnight Cowboy would land the Academy Award for Best Picture. Funt recognized a golden opportunity to capitalize on the libertine moviegoing spirit, and proposed to the top brass at United Artists a sex-themed riff on Candid Camera, for release at feature length in theaters willing to abide by its oodles of nudes. Freed from the oppressive yoke of the FCC, he could stick gaggles of undressed gals and guys in premises poking at the most tender nerve of all. Nothing provokes more anxiety or excitement than sex; for a man on an unending mission to figure out what makes people tick, this was the final frontier.

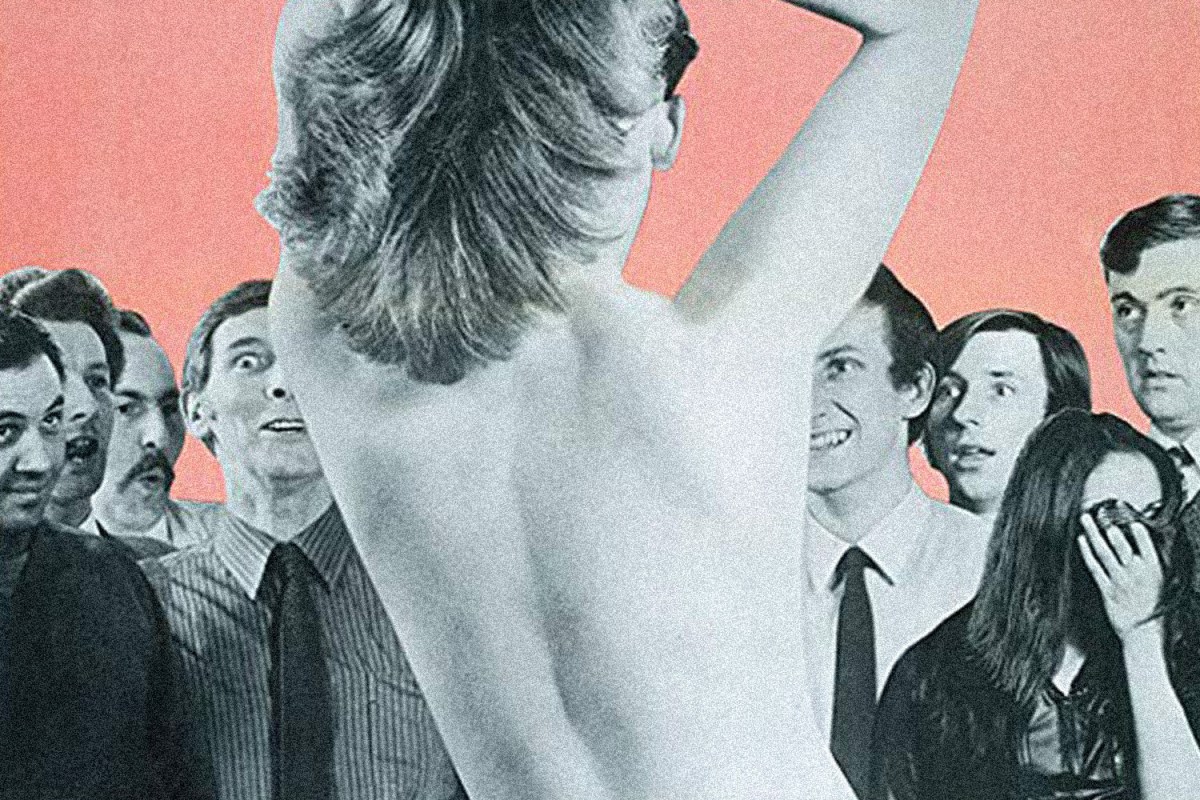

The flirty What Do You Say to a Naked Lady? opens with a framing device, as viewers file into a small screening room and settle in for the film itself. A fleet-footed pop track informs us: “These are real people you’re gonna see / people like you and people like me! / These are real people, caught unaware / none of these people knew we were there!” We intermittently return to the black-and-white footage of these focus groupers and their instant reactions to the scenes we’re watching along with them, a self-reflexive critique that effectively proves Funt’s point for him. Outraged oldsters bellow that he shouldn’t show this cheap piece of filth anywhere decent folk call home, while hipper youths affirm that it’s no big deal. Others defy the generational characterization, whether it’s surprisingly open-minded geriatrics or prudish teens. His sole thesis — that everyone has their own sexual profile and that it’s all good, man — is proven first in the margins.

The film begins in earnest with a harpsichord-laden, Mamas-and-the-Papas-type theme song courtesy of commercial jingle legend Steve Karmen (of “I Love New York” fame), which poses a query to the viewer: “What do you say to a naked lady / one that you barely know?” While the song plays, we watch an average joe round a corner and bump into a woman in her birthday suit. After he collects himself and they go their separate ways, he flashes a devious grin, and there we have the whole of Funt’s project in miniature. It’s difficult to discern where the armchair pop-psych ends and the indulgence of his own randiness begins, because he sees no line separating them. He believed that the study of sex should be funny, goofy and altogether informal. What’s the point of doing this if it’s not fun? Why bother pretending there’s no pleasure to be taken in the work?

He flits through his series of provocations and observations with impish glee, often popping out and identifying himself to wrap up a segment. The pranks, as risky as they are risqué, generally work because Funt has a steady sense of who the butt of the joke should be. He gets his yuks at the expense of creeps, reactionaries and fuddy-duddies by exposing hypocrisy and close-mindedness they’d otherwise keep to themselves. In one bit, Funt sends a black man and a white woman to furiously make out in a corner store, and a racist customer unaware that he’s on a hot camera conspiratorially confides in the white shopkeeper that he doesn’t approve. In another, he uses the penis of Michelangelo’s David as a culture-war bellwether decades before The Simpsons, showing how obtuse the Greatest Generation could be about even the most Platonic of nude art.

Funt plays all the hits, cycling through insights already probed by history’s most illustrious perverts. He repeats Solomon Asch’s experiments with conformity, tacitly compelling men to undress by surrounding them with others already doing so. Funt mostly followed the examples of Kinsey, Masters and Johnson, the first pioneers to survey the full breadth of the sexual buffet. The film includes chats with everyone from grade-school children to deviant divorcées about their proclivities, most notable among them a middle-aged woman frankly discussing her fetish for being roughed up during sex. Back in the monochrome test showing, one forward-thinking respondent reasons that what we’ve just seen was too honest to be objectionable. Conversely, to a segment in which a fetching woman sits on a blushing man’s lap, a hardy-looking woman with an Eastern European accent cries, “Any man who cannot get a woman into his lap is no man. He shouldn’t have to go to the pictures to see this!”

Funt positioned himself on the front lines of the sexual revolution, and took pains to distinguish his output from that of common smut-peddlers or the lechers using the paradigm of free love to prey on the credulous. One crucial segment chronicles a casting session between Funt and a prospective model expected to do complete nudity. What initially seems like an unsavory “casting couch” situation turns out to be a professional and fully consensual interaction between collaborators. (“Perfectly respectable!” raves one stunned test viewer.) A song later on — perhaps more melodically upbeat than befits the title card, “A Few Thoughts About Rape” — states in no uncertain terms that a man has to be “an ape” to commit a crime so heinous.

While the jolly abandon he brought to the demimonde of the X-rated ruffled some feathers, he took care to stay on the right side of history. Even a segment in which a handsy tailor gets overfamiliar with the backsides of his female customers, who nonetheless allow him to do so, has an expository point; back in the test screening, one woman affirms that she worked with a guy like that, and “as nice as he was, he got his little feels in.”

Nevertheless, the film faced the expected response from a nation not so far removed from its Puritan roots. Roger Greenspun, in his review for The New York Times, described parts of the film as “unspeakably vulgar.” The reviewer for Variety missed the point even more spectacularly, writing, “This could have been done as well with suggested nudity or even partial exposure, but Funt confronts several supposedly uninformed individuals with a completely naked female …” That’s like saying that all the plot points in West Side Story could have been communicated just as easily without the singing and dancing. Funt promoted the notion that sex and nudity could be perfectly valid avenues of entertainment unto themselves, no more gratuitous than the production numbers in a musical or the killings in a horror picture.

He used horniness — another word for the honest admission that as human beings, we find sex and sexual images desirable — as an essential piece of his larger endeavor to demystify and de-stigmatize the erotic. What Do You Say to a Naked Lady? imagines a more abiding world, where we’ve all gotten over ourselves and learned to laugh about our kinks, our hangups and our insecurities. It’s a utopian vision of equal-opportunity ogling, with strapping men and slinky women alike inviting the audience to join in a volitive peep show. It’s here that the film’s 50 years of age start to betray it, not incidentally. The American studio system has grown so petrified of depicting the act of lovemaking that it can only be done if first laundered through violence (Red Sparrow) or genre scare quotes (The Shape of Water, referred to through nervous giggles as “the movie where she fucks the fish”).

The last Hollywood-caliber example of a mutually pleasurable sex scene driven purely by the love of the game is hiding in 2018’s Superfly remake, a film seen by few and written about by even fewer. It’s almost for the best that Funt passed away when he did, in 1999, at the apex of the industry’s brief dalliance with such envelope-pushing sexed-up thrillers as Fatal Attraction and Basic Instinct. If he knew how buttoned-up his oddball passion project would make today’s movie culture look, he’d sink back into the earth from whence he came.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.