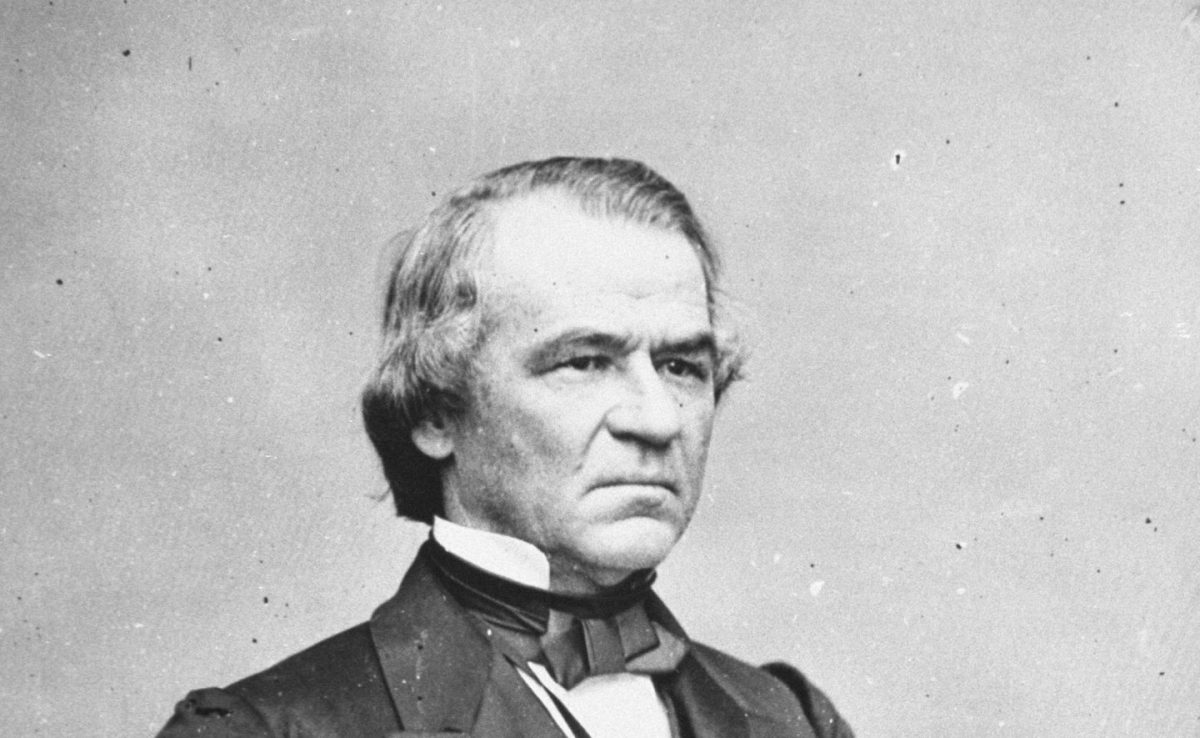

It has now been a year since Donald Trump’s inauguration on January 20, 2017. By virtually any standard, it has been an unusual 12 months. Yet it’s still just-another-day-at-the-office compared to what America experienced under Andrew Johnson. Tasked with the impossible feats of following Abraham Lincoln and bringing America back together after the Civil War, Johnson quickly proved to be the exact opposite of Abe: shortsighted where Lincoln was far-seeing, vengeful where Lincoln was forgiving, egomaniacal where Lincoln was humble … and incredibly racist to boot. (Even by the standards of a white man raised in the South during the 19th century, Johnson was a bigot.)

Lincoln has become a mythic figure in American and world history. This is true if you only know the broad strokes of his story: the boy who goes from a log cabin to the White House and holds the nation together only to be killed just as he is on the verge of again experiencing peace. It becomes even truer as you dive deeper: anyone who suffered from depression can’t help but be inspired by Lincoln successfully battling this affliction, even in the face of horrific personal tragedies. (He outlived two of his four sons.) Truly, Lincoln’s tale is so remarkable a novelist would hesitate to invent it.

Johnson has a story equally unbelievable. It is less remembered, however, most likely because our nation would prefer to pretend it never happened. Coming to power at a time when America was uniquely traumatized, Johnson proceeded to inflict additional traumas with impressive speed.

The Intoxicated Inauguration

To this day, no American leader has done a worse job of introducing himself on the national stage. Lincoln chose Johnson to be his running mate for the second term, replacing Hannibal Hamlin. Johnson’s inaugural speech on March 4, 1865, was his chance to let Washington know why Lincoln believed in him. Indeed, as a native of Tennessee who remained loyal to the Union, Johnson could have helped demonstrate the North and South could work together as the nation rebuilt itself.

Unfortunately, Johnson had a cold and attempted to treat it with whiskey. In what seems more like a sitcom plot than an actual moment in American history, Johnson was drunk at Lincoln’s inauguration. You can read about these events in depth here: suffice to say, Johnson was alternately aggressive and disoriented in a way that humiliated both himself and Lincoln.

Following this, Johnson tried to keep a low profile, staying largely out of public view. In time, it’s possible his debut would have been forgotten. This was an era long before video and, with the Civil War finally ending, there was plenty of more pressing news.

Except Johnson was abruptly thrust back in the spotlight just weeks later with Lincoln’s death on April 15. This presented another complication.

The Assassination Conspiracy

Lincoln wasn’t the only target of John Wilkes Booth. He had assembled a network intended to wipe out Johnson, Secretary of State William Seward, and potentially even General Ulysses S. Grant. Grant’s decision not to attend Ford’s Theatre with Lincoln spared him one attempt. (Ron Chernow’s book Grant notes the general also received a mysterious letter suggesting a second effort had failed.) Seward was brutally stabbed but survived.

Johnson was staying in a D.C. hotel alone and this was a very different era regarding security—the Secret Service wouldn’t even be created until later in 1865. Once again, inebriation played a major role in Johnson’s life, this time for the better. Instead of killing Johnson, his aspiring assassin got drunk and abandoned the plan.

Booth did manage to wound Johnson. Hours before shooting Lincoln, he left Johnson a note reading, “Don’t wish to disturb you Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth” The result was that even a century later, theories continued that Johnson was somehow involved in Lincoln’s killing.

The writer Finley Peter Dunne famously proclaimed, “Politics ain’t beanbag.” It is a brutal profession where people are inclined to think the worst of you. Johnson’s rivals looked at him and saw a drunk or even a man who helped murder Lincoln for his own gain.

This is to say Johnson took office carrying a tremendous amount of baggage. He also faced a uniquely trying task.

Replacing a Saint

George McClellan served for a time as general-in-chief under Lincoln. Stephen W. Sears’ The Young Napoleon observes that, after Lincoln’s death, McClellan wrote, “How strange it is that the military death of the rebellion should have been followed with such tragic quickness by the atrocious murder of Mr Lincoln! Now I cannot but forget all that had been unpleasant between us, & remember only the brighter parts of our intercourse.”

Of course, when he had served Lincoln, McClellan regarded Abe with utter contempt. He went so far as to taunt him as a “Gorilla.” This was not uncommon: the combination of Lincoln finally achieving victory and then dying suddenly turned those who mocked him in life into devoted mourners.

And with this, Andrew Johnson—the man who got drunk at the inauguration and received a mysterious note from Booth shortly before Lincoln’s assassination—took center stage.

The Blessing of Low Expectations

Johnson’s initial efforts in the White House were fairly well received. Just by being sober, he was doing better than many had hoped. Americans, in general, were grateful the Civil War was over. The pursuit and capture of Booth provided an additional unity. Johnson also allowed Mary Todd Lincoln to stay in the White House for weeks while she grieved and kept Lincoln’s cabinet, providing reassurance for those uncertain of his leadership.

Yet there were ominous inklings. The former slave turned abolitionist Frederick Douglass first encountered Johnson at the inauguration. Douglass wrote that after Lincoln pointed him out to Johnson, the “first expression” that came to Johnson’s face was “one of bitter contempt and aversion.” When Johnson became aware Douglass had noticed him, he assumed a “more friendly appearance.” Douglass was still disturbed: “His first glance was the frown of the man; the second was the bland and sickly smile of the demagogue.”

Douglass suspected that, if given the chance, Johnson would be an enemy to blacks. His impression proved to be depressingly accurate.

A Strange Man With Strange Views

The quote “I am sworn to uphold the Constitution as Andy Johnson understands and interprets it” is often attributed to Johnson. Whether or not he said it, this sums up Johnson pretty well. Johnson was fearlessly committed to principle, but only principle as he personally recognized it. Johnson held a troubling mix of views: he had a tremendous contempt for blacks and championed a “white man’s government,” an idiosyncratic take on the Constitution (notably his belief that since secession was forbidden, it had technically never occurred), and a megalomaniacal view of himself. Speeches by Johnson sometimes devolved into Johnson repeating how heroically he took on his seemingly endless list of enemies from both the North and the South.

Johnson’s belief that states could never leave the United States meant accepting the Confederacy back into the U.S. was basically a formality. While others argued about the changes that would need to occur in those states to ensure the problems that caused the Civil War never happened again, Johnson was willing to leave them largely to their own devices. [David O. Stewart’s Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy gives far more detail on Johnson’s view of the Constitution and the former Confederacy.] There was an upside to this: it caused Johnson generally to advocate a merciful approach to dealing with the defeated rebels. This was consistent with the beliefs of the late Lincoln and Grant, who both advocated generosity with the vanquished.

Indeed, early on Grant and Johnson seemed largely in agreement. On December 18, 1865—the day the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery went into effect—Grant issued a report Concerning Affairs of the South. He offered some bold conclusions: “I am satisfied that the mass of thinking men of the south accept the present situation of affairs in good faith.” (In other words, former Confederates had generally come to terms with the fact that blacks were free and would treat them accordingly.)

In support of that position, Grant offered up… well, very little. The report was based on Grant’s tour of the South, but it had been a brief one. Grant acknowledged he didn’t even leave Washington until November 27—he was making sweeping assertions based on a two-week trip.

Grant would soon come to feel he was badly mistaken and fully recognize the side of Johnson that was less benevolent. While Johnson accepted that slavery was officially over, he wanted to ensure that the South otherwise remained largely as it had been. In particular, he was convinced that blacks gaining rights (and, worse, power) would result in the oppression of whites, particularly whites without money. Johnson once opposed a bill because it “would place every splay-footed, bandy-shanked, hump-backed, thick-lipped, flat-nosed, woolly head ebon-colored negro in the country upon an equality with the poor white man.” During the Civil War, he declared, “Damn the negroes. I am fighting those traitorous aristocrats, their masters.”

Johnson fully displayed these attitudes during the second encounter with a man from his past.

Meeting Frederick Douglass: Take Two

Their first meeting was bad. This one was much worse. On February 7, 1866, Douglass and other black leaders came to lobby for a civil rights bill. Johnson inexplicably chose to tell them about his days as a slave owner, noting he was so kind to his slaves that he was “their slave instead of their being mine.” Johnson also informed them the bill troubled him because if blacks got the vote, it would result in poor whites being essentially kept “in slavery.” (Again, Douglass had experienced actual slavery—during a particularly brutal chapter in his life he suffered daily whippings.)

After the meeting, Johnson was apparently delighted with his own performance, telling his secretary, “Those damned sons of bitches thought they had me in a trap.” He also noted that Douglass was “just like any n—–” and would “sooner cut a white man’s throat than not.”

On February 19, Johnson vetoed the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, blocking an effort to provide land and general support to displaced Southerners including freed blacks.

Three days later, Johnson gave the Father of Our Country a birthday to remember.

The Washington Speech

On February 22, 1866, Johnson delivered what he termed “extemporaneous remarks” to celebrate George Washington’s birthday. They stretched on at epic length, despite Johnson occasionally suggesting he planned to wrap up. (Readers of the text will note his use of phrases, “I have talked longer now than I intended” and “I have detained you longer than I intended,” only to be followed by hundreds of additional words.)

The address displays all Johnson’s flaws, including rampant egotism (“Who, I ask, has suffered more for the Union than I have?”), paranoia (“…before our brave men have scarcely returned to their homes to renew the ties of affection and love, we find ourselves almost in the midst of another rebellion”), and general deep resentment. Indeed, after strongly implying his political enemies were traitors, he happily named them: “I say Thaddeus Stevens, of Pennsylvania. I say Charles Sumner. I say Wendell Phillips, and others of the same stripe, are among them.”

Stevens and Sumner had supported the Union, were still in Congress and belonged to the same political party as Johnson.

Oh, and Johnson suggested people were coming to kill him. (“I make use of a very strong expression when I say that I have no doubt the intention was to incite assassination.”)

On March 27, Johnson vetoed the civil rights bill. He stated it was unacceptable to offer blacks more than the government had “ever provided the white race.” The Republican Congress overrode his veto. Less than a year into his term, he was in an open war with his own party.

Politically, Johnson could take comfort in his relationship with Grant. As a military leader, Grant felt it wasn’t his place to take public stances on political matters. As a result, the most popular man in the North declined to speak out, even as it became clear he and Johnson differed on many issues. The general wouldn’t champion Johnson’s positions—and wasn’t particularly fond of a man he called “revengeful”—but he didn’t openly criticize them either. A shrewd politician might have been grateful to have a potential rival neutralized.

No one, however, ever accused Johnson of being shrewd.

Later in 1866, Johnson began summoning Grant to attend his speeches. By having Grant on stage with him, Johnson created the impression that Grant enthusiastically endorsed him. Indeed, Johnson dragged Grant along as he launched a three-week tour covering 2,000 miles. Johnson wanted to explain why freed blacks didn’t need to be guaranteed rights or otherwise protected… and he wanted to do it in the North.

It was, even by Johnson standards, a bad idea.

The tour proved as strange as the inauguration. Johnson was reportedly upset by occasions when Grant received more applause than he did; Grant didn’t want to be there in the first place. Rumors spread that both Johnson and Grant had started drinking heavily again. Grant wrote to his wife, “I have never been so tired anything before as I have been with the political stump speeches of Mr. Johnson. I look upon them as a national disgrace.”

Grant had stoically endured the Civil War’s savage combat for years—Johnson broke his spirits in weeks.

In 1868, the Party of Lincoln held onto the White House, only with a new occupant: Ulysses S. Grant. Johnson had barely managed to reach the end of the term, becoming the first President to be impeached by the House and avoiding conviction in the Senate by a single vote. No one can say the exact moment Grant began to seriously embrace the notion of seeking the presidency, but Johnson’s treatment surely sped him along to that decision.

While Johnson only served a portion of a single term, his legacy was intact. Reconstruction was destined to be a difficult task, but Johnson’s actions after Lincoln’s death ensured it would be a slow, nightmarish process. While Lincoln tirelessly strove to reunite America, Johnson fought to ensure we remained divided racially and politically. No wonder we do our best to forget him.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.