Late last year, Jennifer Doudna called for greater oversight and regulation of genetic editing. Given that Doudna is the co-inventor of CRISPR, this declaration had a significant impact in the scientific community. In n article published in Science, Doudna offered a balanced but cautious view of the future, writing that “stakeholders must engage in thoughtfully crafting regulations of the technology without stifling it.”

Since then, a lot has happened in the world of CRISPR, including Doudna being awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Emmanuelle Charpentier. But a new study by Columbia University geneticist Dieter Egli offers some caution as the technology moved forward — caution that resonates with Doudna’s earlier statement.

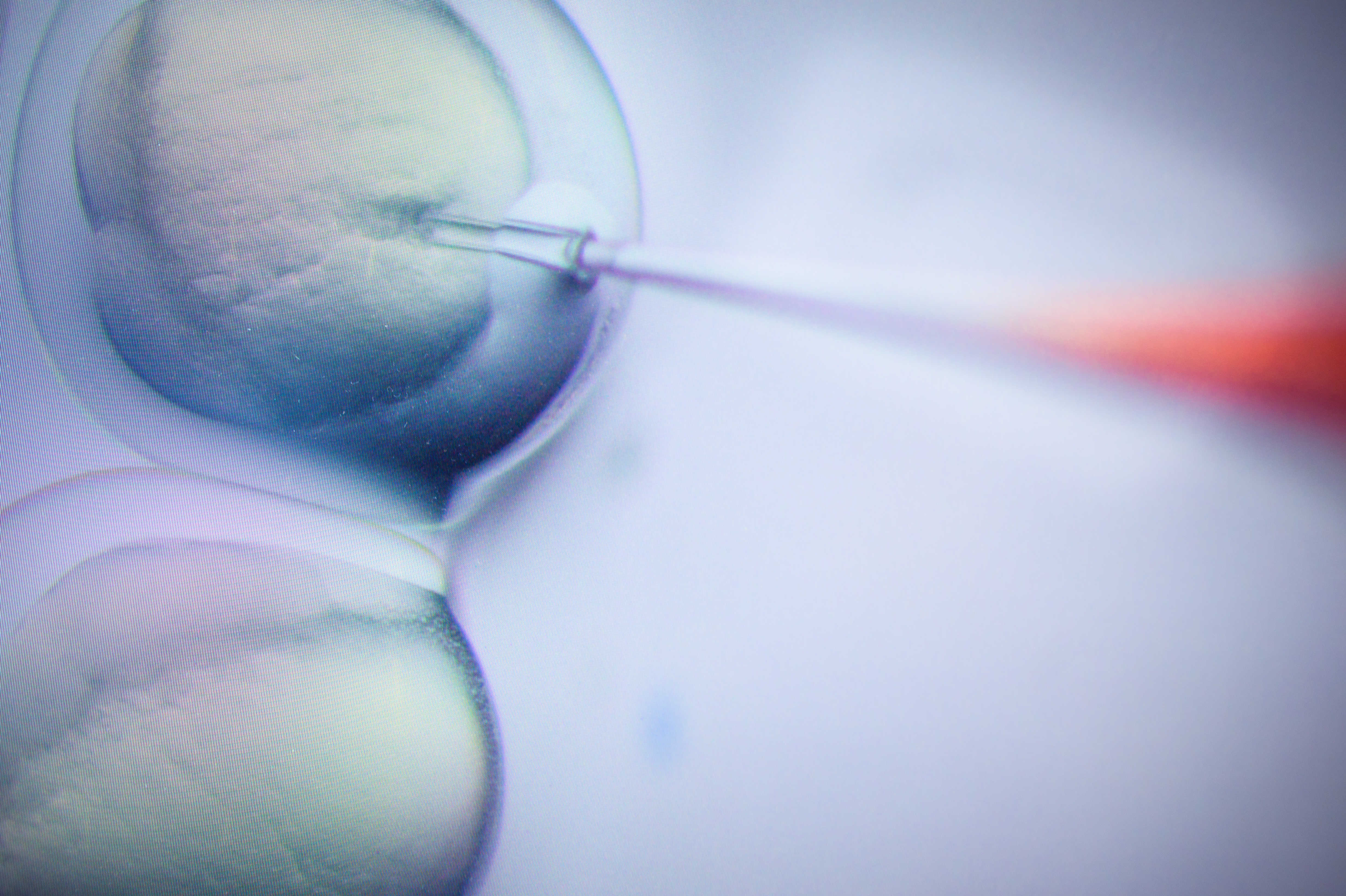

Writing at The New York Times, Katherine J. Wu explored the study’s findings and its ramifications. “Administered to cells to repair a mutation that can cause hereditary blindness, the Crispr-Cas9 technology appeared to wreak genetic havoc in about half the specimens that the researchers examined,” Wu writes — suggesting worrying side effects when CRISPR is used to alter genes in embryos.

The article notes that “[s]everal of the cells managed to sew the Crispr-cut pieces of DNA back together with a few minor changes,” but for half, the damage was sufficient to remove large pieces of chromosomes.

“They were talking about trying to repair one gene, and you have a substantial fraction of the genome being changed,” said Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center geneticist Maria Jasin, who was one of the study’s authors.

The full ramifications of the study have yet to be seen, and the scientists quoted in the article have differing opinions on what can be gleaned from all of this. And as with so many things involving CRISPR, this knowledge remains a work in progress.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.