This year’s hurricane season has already proven one of the most brutal in American history, with Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria unleashing torrents of rainfall and leaving behind untold destruction in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico. Hundreds have been killed, thousands left homeless, and cleanup costs are ballooning into the billions.

For many of us, the only connection we have to the death, displaced, and damage of a hurricane zone is what we see flashing across our TV screens or smartphones. And maybe after texting a donation to a faceless relief organization, we call it a day.

Forty-year-old William McNulty is not one of those people. If there’s a hurricane, an earthquake, wildfire—hell, any natural disaster—you can count him in. “Service is in my blood,” McNulty tells RealClearLife. “It was important to my family, it was part of my education as a young adult, and has been an important theme throughout my entire life.” He’s taken that ethic and run with it, founding and now serving as the chief executive officer of Team Rubicon Global, a nonprofit organization that puts the world’s military heroes at the forefront of disaster response and relief. And they do it all free of charge.

McNulty served eight years and a month in the Marine Corp, splitting his time between the infantry and intelligence. When he tells us he was raised in a “military family,” it seems like almost an understatement; both of McNulty’s grandfathers fought the Japanese in the South Pacific during World War II, both grandmothers were war brides, and his father, a retired corporate finance worker, was a Green Beret. “[Military service] wasn’t anything that was ever pushed upon me, but I felt a calling to serve,” says McNulty. As if needing to drive home the point, he then rattles off his credentials, in short, sharp monotone: “An Indian Guide; a Cub Scout; a Boy Scout; a Jesuit student; a Marine; serving the intelligence community; and then I founded Team Rubicon.”

Unlike most of the veterans whom RealClearLife has profiled thus far, McNulty didn’t enlist straight out of high school—and did so, almost a full year before the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Armed with a dual bachelors degree in economics and communications from the University of Kansas, McNulty “decided that it was now or never,” and signed his life over to the Marines. Whereas many college graduate enlistees might choose to go the Marine Corp Officer route with a four-year degree, McNulty was hellbent on joining the infantry. “Because I wanted to know what it was like when sh-t rolls downhill,” he says. That is, he believed that being an enlisted infantryman would make him a better leader someday.

For the first part of his career as a Marine, McNulty would serve as a TOW gunner—a specialist in an anti-tank missile system that is deployed either on the ground or atop a Humvee. (Picture a team of soldiers carrying the weapon system’s components on their backs, Voltron-ing them together, and then unleashing hell on the enemy.) He did stints in Korea and briefly in Japan before making a lateral shift to Marine intelligence. He would complete two tours in Iraq as an intelligence officer—one in 2004-05, the other in 2008-09—between which he earned a Masters in government from Johns Hopkins University. In the Middle East, he was tasked with “human intelligence,” or gathering intel from Iraqi civilian sources and detainees, a job he admits wasn’t always that safe, because you often didn’t know who you were dealing with.

As McNulty tells RealClearLife, one such intelligence mission stood out to him in particular because of how close to home it hit. It came about in the aftermath of a deadly ambush by insurgents on an Army convoy on Good Friday in 2004. The attack left eight dead and saw two men, including Private First Class Keith Matthew Maupin, taken hostage (he was posthumously promoted to Army staff sergeant). “[Sgt. Maupin] was a POW who was captured in April 2004 not far from my forward operating base at the time,” remembers McNulty. “My team worked tirelessly to repatriate him and ultimately, developed the human intelligence leads to bring him back home.” Following up later with McNulty via email, he clarifies that, at the time, there was insufficient evidence of whether Sgt. Maupin had been murdered by his captors or was still alive; a video of his execution had surfaced, but it was “inconclusive.” And by May 2005, McNulty had left Iraq. It would take three more agonizing years before the military was able to locate Maupin’s remains and give his family closure.

“The case of Matt Maupin was so important to me, because my grandfather’s brother is still missing in action,” says McNulty. A PBY reconnaissance pilot in the Navy, McNulty’s great uncle Jim had been on a mission searching for the Japanese fleet near the Aleutian Islands when he and his co-pilot doubled back to search for a fellow pilot who’d gone missing. They, too, disappeared and were never heard from again. Then, after seven years of waiting, his grandfather’s family was informed by the Navy that Jim had been declared killed in action. His body was never recovered. As a child, says McNulty, his grandfather had told him that Great Uncle Jim was “living on a desert island full of naked girls.” It was a tall-tale he’d believed like that of Santa Claus or the Tooth Fairy. It was part of his family’s lore. And you can’t help but think: At least the Maupin family knows.

After McNulty retired from Marine intelligence, he says he found himself in a similar position to many recent military veterans, facing “the challenges of reintegration.” These being the simultaneous feelings of “freedom” in not being part of the regimented military lifestyle anymore; and helplessness of not knowing how to cope with civilian life again. McNulty says he sought help for this transition. He also dropped off the map. “After Iraq in late 2009, I went to Mexico to give myself whitespace,” he says. It was there that he realized he wanted to continue to serve in some way, but he had no marching orders.

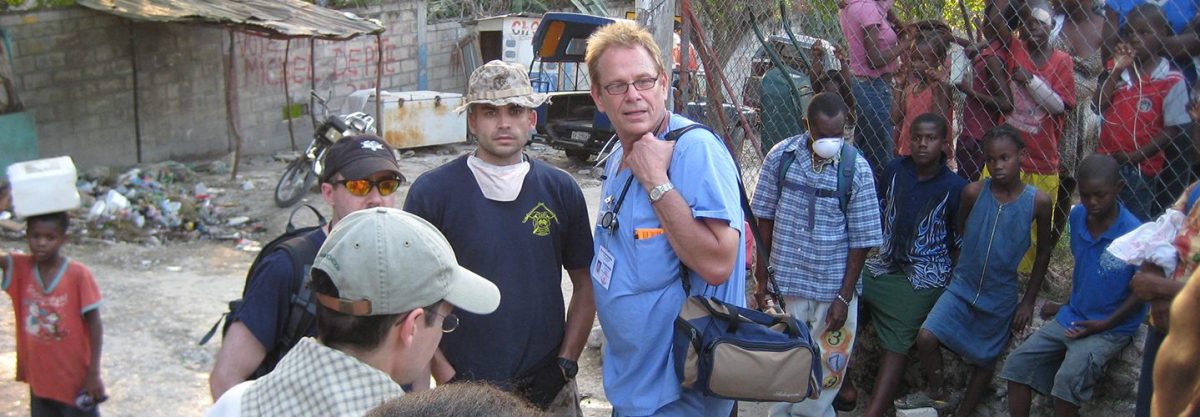

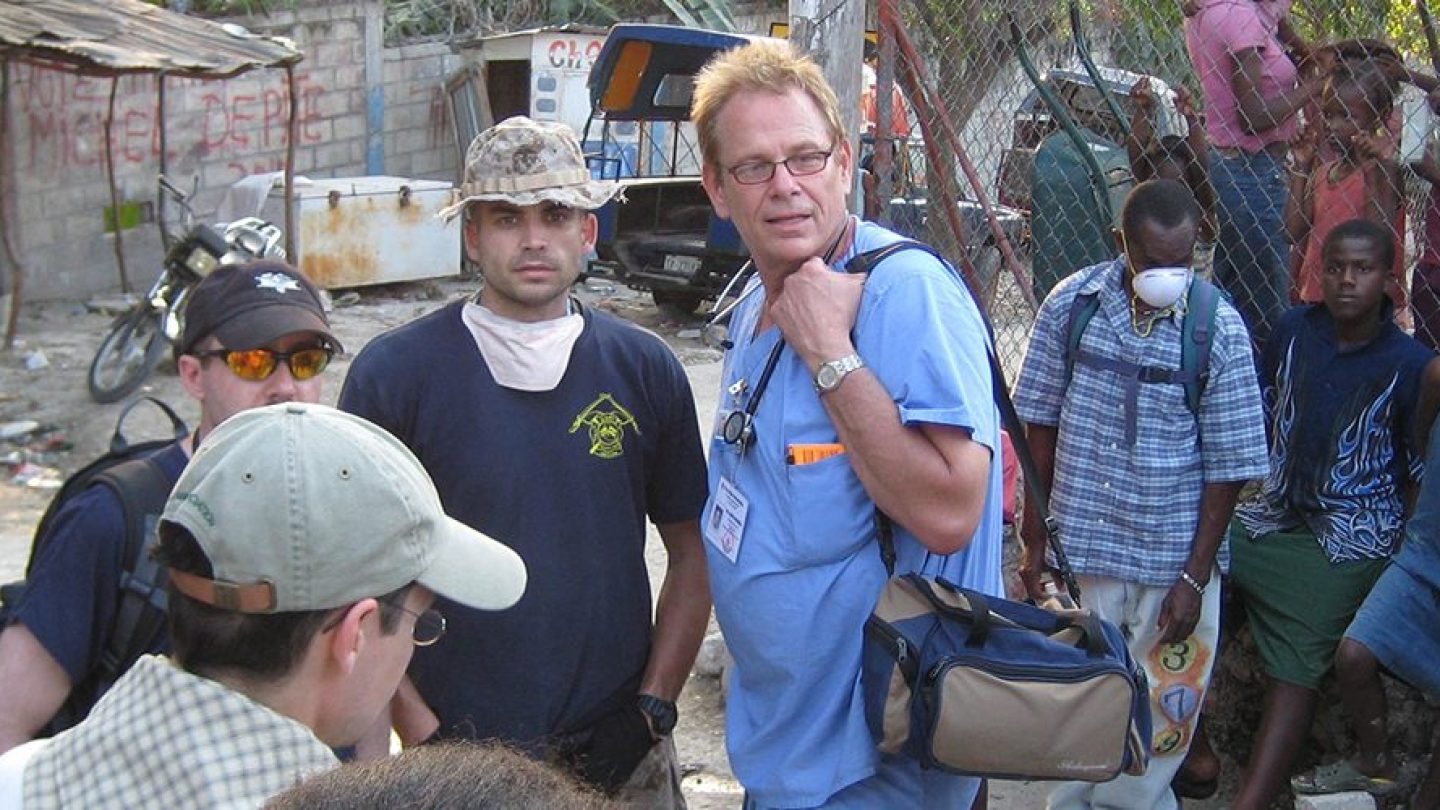

And then fate struck in the form of a massive earthquake. On January 12, 2010, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake hit Haiti, its epicenter less than 20 miles from the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince. Just watch some of the initial news footage, and you’ll remember how devastating it was; it looked like the site of a war zone. The earthquake killed hundreds of thousands of Haitians, displaced millions, and left the already poor nation in shambles. McNulty sprung into action. Along with ex-Marine and milblogger Jake Wood—whom he hadn’t met in person until the day before their first mission together in Haiti—McNulty co-led a medical team. It consisted of a group of family doctors (including his own) from Chicago. They went in with a rented truck packed full of supplies to the disaster zone that was Haiti. The team had four military veterans in total (besides McNulty and Wood), who acted as an “advance team” for the doctors. They ended up treating thousands of patients in places too perilous for most to venture to.

It was there that Team Rubicon was born.

If you’re wondering about the organization’s name, it’s in reference to Julius Caesar’s famed (and decidedly, ballsy) crossing of the river Rubicon in 49 B.C. on his way to invade Rome. It’s since become a common metaphor for the line one crosses in committing to something greater—or off limits. Team Rubicon evolved into just that: an organization that goes the extra mile, despite inherent danger, to basically fix the world where it’s been broken. It accomplishes this by hiring volunteers, who have served in the military and as first-responders, and have that je ne sais quoi needed to block out the fear and execute. “First and foremost, we are a best-in-class disaster response organization, but through that service, it gives veterans a renewed purpose, community, and identity after taking off the military uniform,” explains McNulty.

McNulty’s organization has since expanded to become Team Rubicon Global, an international offshoot of the original concept, which he tells us is comprised of over 55,000 registered volunteers. They currently have boots on the ground in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico; as well as Dominica in the British Virgin Islands, which was pulverized by Hurricane Maria. Team Rubicon Global includes volunteers from Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, and of course, the U.S. McNulty tells us that his veteran volunteers bring to the table “hard and soft skills” that they “earn in the military,” which include “teamwork, decisive leadership, risk-mitigation, emergency medicine, logistics, [and] heavy equipment training.” He says that it’s Team Rubicon’s goal to “capture and harness” these skills in veterans before they “atrophy.” Not to mention, help these veterans grow by training them in things like wildland firefighting and wilderness medicine.

Of course, the teams on the ground in Puerto Rico and Dominica can’t help every single person that’s been affected by the hurricane. To that end, says McNulty, “we focus on the uninsured and underinsured. …These are people who often don’t have the requisite insurance for the disaster that’s just affected them.” For example, many of the people that Team Rubicon assisted in Houston didn’t have flood insurance because their homes weren’t in flood plains. “Their options, at that point, in order to do the mucking and gutting work, were pretty limited,” says McNulty. This could either mean having to lean on a community organization like a church or friends and family to help out with the dirty work; or hire a restoration service like ServiceMaster or ServPro, which could cost someone anywhere from $25,000 to $40,000. As we mentioned above, Team Rubicon does it all free of charge.

Like many nonprofits, McNulty’s is unabashedly apolitical; RealClearLife got complete static when we asked him to comment on President Trump’s decidedly slow response to the crisis in Puerto Rico. That’s because, like any good nonprofit, Team Rubicon will accept any and all donations, no matter who they come from (obviously, to a point). To wit, in a single highlight reel of media references (see above), Team Rubicon gets name-checked by former presidents Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and George W. Bush. What about Trump, though, we asked? “He just donated $25,000 to our response [in] Texas to Hurricane Harvey,” says McNulty. How did it go down? “We read about it in a White House press release.”

By the way, if you’re interested in getting involved in Team Rubicon, you don’t have to be a war veteran or have a medical degree: “Team Rubicon is not only open to military veterans and first responders, but also to ‘kick-ass civilians,’ as we like to call them,” says McNulty. Do you have a skill set that might be helpful to the team? If you’re in the U.S., you can learn more about Team Rubicon here. And besides those teams in Australia, the U.K., and Canada, two more countries will soon be joining the cause: Norway and the Netherlands.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.