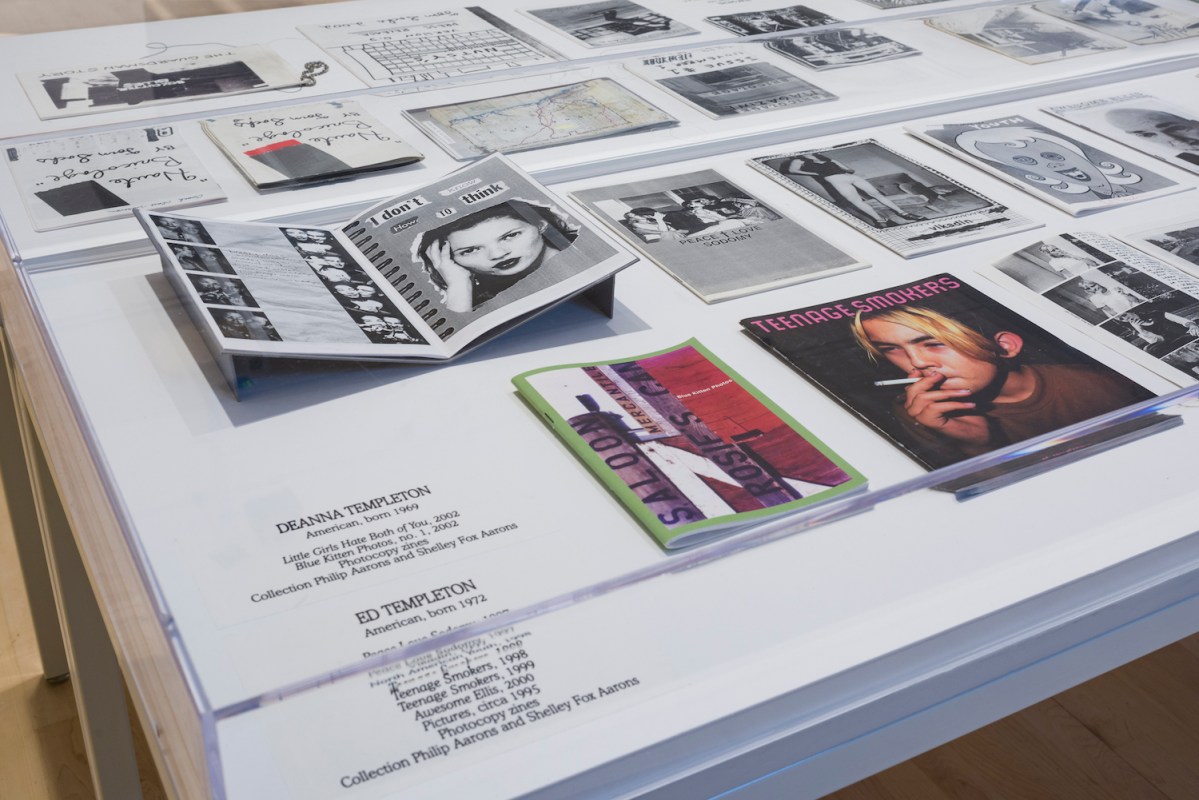

“Why Vaginal Davis, what a pleasure it is to see you here!,” I say to myself as I’m walking through the new Brooklyn Museum exhibition “Copy Machine Manifestos,” which presents work from 1969 to the present and chronicles independently-produced North American publications as both art form and countercultural symbol, force of rebellion and community. The work of renegade performance artist and musician Vaginal Davis is among them. Her zine, Fertile La Toyah Jackson, is on view, a beloved Bay Area publication that chronicled drag and queer culture and was an essential contribution to the Queercore scene. Interspersed throughout the show are also works chronicling the life of zines off the page: paintings, video from handheld camcorders, t-shirts, photographs and more. Many counter cultural icons’ work is in the show — from the legendary Raymond Pettibon, designer of the famed Black Flag logo, to David Wojnarowicz to Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill and Le Tigre.

Zines were, and remain, an essential way to tell stories outside of the mainstream, to become the voice instead of being spoken for. In the zine world, people did this with paste-ups and a Xerox machine, where others may have taken to the microphone; though frequently, as exhibition co-curator Drew Sawyer says, there was an overlap across a multitude of media. He cites, for example, the writer Brontez Purnell, whose zine Fag School is on view along with a video of the artist reading from it. Purnell was also in the band Gravy Train!!! and has since become a lauded multihyphenate.

The zine has an interesting past. Accordinging to Sawyer, it’s an artistic pursuit, but in many of its incarnations, it’s also a reaction against the publishing industry, art market, art world politics and art institutions. That so radical a form would evolve in the United States is by no means unthinkable; rather, it was perhaps right on schedule given the upheaval of the 1960s and the progressive socio cultural and political movements that grew out of it in the following decades, punk chiefly among them. Indeed, a large chunk of the exhibition’s first portion is culled from punk’s many lives across the country and follows the DIY spirit through several subcultures and communities.

Even the way zines were produced were an aspect of community building and resistance. In the early years of Xerox machines, it would be highly unlikely for someone to own one the way we have printers and scanners. They were predominantly housed in businesses, and intrepid zine makers with office jobs, or who had friends with office jobs, would print them on the company’s dime. Or, as co-curator Branden W. Joseph says, you’d have a co-conspirator at the copy place who’d do you a solid whenever you wanted to print a new zine. “That clandestine, parasitic nature of taking resources from the mainstream…it is really a part of it,” Joseph says. Plus, you’d make your zine at the copy place and leave it there for others to enjoy, making that kind of store a community space on its own.

Is LA the Country’s Best City for Art?

The Hammer’s architectural transformation — and an important new biennial — has put it at the center of a radical evolution

It’s an interesting moment for a show like this, the production of which began in 2019. There’s an ongoing progressive push towards community strength and reclamation of narratives, a thought process intrinsic to zinemaking. But I also think of the New York Art Book Fair, where many artists sell zines, and how it had lines of chicly attired young people around the block when it moved to its new location among the Chelsea galleries in 2022. Cleveland’s Museum of Contemporary Art hosts Bound Art Book and Zine Fair, and the University of Kansas and the Aperture Foundation both host zine-making workshops, as do many others. Will the zine become mainstream? What will happen to it if it does? The fashion world has adopted the form in many instances — Jacobs cites Gucci, for example — and such a phenomenon begs the question of who might be next to take up the mantle.

With an understanding of the inherently rebellious nature of zines, one that has largely been underground and by choice, it’s interesting to zoom out and consider the mere existence of an exhibition like “Copy Machine Manifestos” now. What does it look like when an artform that has, for most of its life, been distinctly anti-institutional becomes institutionalized?

“One of the things that we talked about early on when engaging with this exhibition is it would be a missed opportunity if we weren’t able to inscribe the zine into the history of art through this,” Jacobs says. “But at the same time, it would be a failed opportunity if the history of art looks the same after you have engaged.”

Sawyer shares that, given the philosophical nature of this conundrum, every artist in the show was asked if they wanted to participate if the work was sourced from an archive, a collector or another outlet outside the artist themself. Joseph also mentions that there has been an institutionalization of the form for many years, with zines now appearing in the collections of places like New York University’s Fales Library, the Pacific Film Archive, the University of Iowa, The Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art’s Thomas J. Watson Library, among others. Work like this largely hopes to preserve these objects that were once distinctly ephemeral and asks that they be considered not just artwork but artwork essential to community building.

“Hopefully the show really foregrounds the role that zines have played in networking amongst artists, in creating counterpublics, in creating a sense of community outside of dominant systems,” Sawyer says. “That was true in the 1970s, and I think it’s as true today.”

“Copy Machine Manifestos” is on at Brooklyn Museum until March 31, 2024.

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.