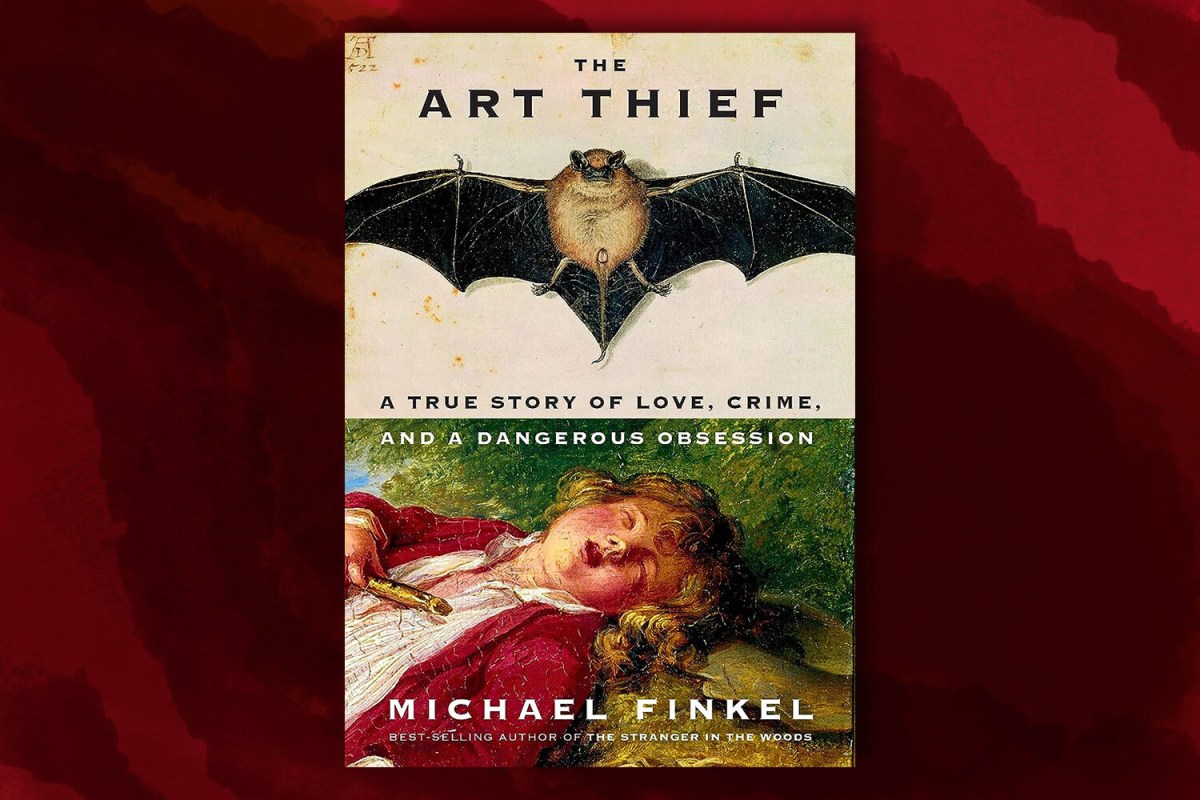

From the moment he read about him, Michael Finkel knew he wanted to tell Stephane Breitwieser’s story. He remembers looking at newspapers and small websites, wishing to learn French at the time, discovering the Frenchman’s story and becoming hooked. Breitwieser, currently serving a seven-year prison sentence, is the most prolific art thief in the history of the world.

Three things about Breitwieser intrigued Finkel: the insane quantity of his conquests, the fact that the thief never hurt anyone during his crimes and that he professed to steal art not for money but for love. “Whose heart doesn’t melt a little bit right there?” Finkel says over Zoom.

It’s impossible, a French journalist friend warned him. Breitwieser doesn’t talk to the press. This simply solidified Finkel’s resolve. “Game on,” he said to himself. Breitwieser became the author’s inspiration to learn French as quickly as possible. He wrote letters to the thief, beginning in 2012, and moved to France. It was years before Breitwieser returned Finkel’s letters, but when he did, the pair spoke at such length that Finkel was able to write a book about the man. Breitwieser’s story is so extraordinary that, Finkel tells me, he has sold the movie rights and is fantasizing about Timothee Chalamet playing the lead.

The Art Thief tells the story of Breitwieser’s hundreds of thefts, sparingly using first-hand quotes from the man and staying in the present tense to retain a sense of immediacy. No one can know the exact value of the artifacts that Breitwieser stole, but estimates put it at around $2 billion. In the years between 1994 and 2001, he and his girlfriend Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus stole things from museums at the rate that other people buy milk. It became an obsession of Breitwieser’s and, for a time, Kleinklaus was happy to accompany him.

Breitwieser’s crimes really do leave you open-mouthed. He stole a crossbow in broad daylight and threw it out of a window. He was never caught on camera, despite not wearing a mask at any point. He always acted in a way that was so counterintuitive that his behavior didn’t appear suspicious. After one theft, he and Kleinklaus stayed for lunch in the museum in question. “Something that a thief would obviously never do is precisely what a thief should consider doing,” Breitwieser puts it succinctly.

Born in 1971 in Alsace, Breitwieser grew up in Wittenheim, an area in the northeast of France. When he was young, his mother let him alter the mark on his math report card, knowing this would stop his father getting angry. This was symptomatic of Mireille Stengel’s lenience towards her son — a lenience that turned into a willful denial of his crimes. When he was 19, he worked as a museum guard and stole an old belt buckle: a seminal moment for the young man, who would soon call art theft the only real career he could ever sustain.

On Zoom, the 54-year-old Finkel feels like almost as large a character as Breitwieser, wearing an earring on his left ear and talking at great speed and at great length. “It’s so much easier to talk about a book than work on one,” he says. “I always enjoy running my mouth off about a project that I’m happy with.”

Getting to know Breitwieser was like trying to hold on to water, the author says. After more than a decade of hanging out with him, Finkel still isn’t sure how he feels about the thief. He is at once disgusted by Breitweiser — whom he calls a cancer at one point in the book — and charmed by the man’s child-like wonder. “It changes even as I’m babbling to you — and I like that,” he admits.

Breitwieser has a tendency to feel disgust too — disgust towards other art thieves, whom he considers criminals who use violence or the threat of it in order to deprive museums of their artworks. As Finkel writes, “A violent, late-night heist is an insult to Breitwieser’s notion that stealing artwork should be a daytime affair of refined stealth in which no one so much as senses fear.” He certainly sees himself as more noble than auction houses and art dealers, whom he regards as “the worst,” in Finkel’s words.

What Makes a Successful Art Dealer Break Bad?

All this and a Fyre Festival connection, tooBreitwieser’s first crime with Kleinklaus — really the only person with whom he seems to have had a relationship, other than his mother — was at a museum in Alsace in the spring of 1994, when he was 22. While Kleinklaus kept watch for him — a role she would play expertly over the next few years — Breitwieser took an 18th-century pistol from a display case and the pair sped off, no one on their tail. Soon the two of them were living in the attic of the house Breitwieser’s mother bought in the divorce from his father. They earned next to nothing, Breitwieser seemingly incapable of and uninterested in holding down a job. He didn’t attempt to solve this problem with his spoils; Breitwieser circumvented the art thief’s most serious dilemma by simply keeping his treasure in the attic rather than drawing attention to himself by attempting to sell it. He seems to have had an almost fatal attachment to works of art.

As they lived under each other’s feet, Breitwieser’s mother must have known all about her son’s crimes, thinks Finkel. The attic became covered in expensive artifacts, and occasionally Stengel would even accompany them on trips that included a theft or two. “What an unhealthy relationship between mother and son,” the author says. As a father, Finkel says that Stengel failed in her duties as a parent. There was no one holding Breitweiser accountable for his litany of crimes. “You cannot permit your son to be a serial art thief,” Finkel says.

As Breitwieser continued to steal, it became a matter of time before someone noticed a pattern and caught him and Kleinklaus. In 1996, a Swiss detective specializing in art crime, Alexandre Von der Muhll, picked up the scent. At almost exactly the same time, Bernard Darties and other officers in France picked it up as well.

Breitwieser was never going to get caught red-handed fencing any of his loot. But, never happy enough to stop stealing, he was now playing an increasingly dangerous game. In Switzerland he and Kleinklaus were caught, fined and given a temporary ban from the country — the most serious reprimand yet. Kleinklaus gave him an ultimatum — her or the art — which she then made less strict. Finkel reports that a therapist who analyzed Kleinklaus said that the pair’s relationship had “metastasized into abuse, emotional and perhaps physical too.” When he found out Kleinklaus had had an abortion without telling him, Breitwieser slapped her. (When his parents were married, his father had been violent to his mother as well.)

In Switzerland, where Breitwieser foolishly returned, the pair were finally arrested in November 2001, and the full extent of their crimes was unveiled. Breitwieser protected both his mother and girlfriend from being implicated, but the pair reacted to his arrest in extremely different ways: Kleinklaus refused to talk to him; his mother not only denied all knowledge of his crimes but also threw away and burned all of the attic loot. “I wanted to hurt my son,” Stengel told police, “to punish him for all the hurt he caused me.” Life got worse and worse for the thief as the world learned of his extraordinary crimes. Kleinklaus, who vocally disowned Breitwieser, spent only one night in jail. Let out of prison after being sentenced to four years, though he swore never to steal again, Breitwieser stole a painting alleged to be worth more than $50 million and went straight back to prison after his new girlfriend reported him to the police. He seems incapable of doing anything but stealing art. “Nothing interests me,” he said recently. “I’ve kind of given up.”

Breitweiser’s sad and sorry tale is one of hubris. Even if you are perhaps the best person in the world at what you do, you will make a mistake when you think yourself invincible. This art thief, a man so in love with art that he couldn’t bear the thought of doing anything else with his life, could only run from the law for so long. For most of his life Breitwieser seems to have believed that art in a museum lives a kind of imprisoned life. The irony is that now, under house arrest after being caught multiple times, Breitwieser is imprisoned in the same way.

The Art Thief is out now.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.