One hundred years ago today, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, prohibiting the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors for beverage purposes,” was ratified by the necessary 36th state, Nebraska, and Prohibition took effect.

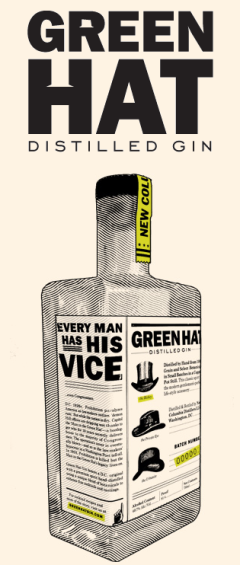

It didn’t take too long after that for George L. Cassiday, who later became known as “The Man with the Green Hat,” to get to work.

A veteran who served with a light tank unit during World War I, Cassiday had been unable to return to his job as a railroad brakeman following his service and instead turned to bootlegging on the suggestion of a friend.

And, Cassiday didn’t put his sights on supplying the cabinets of speakeasies with his illegal hooch, he set them on supplying cabinet meetings on Capitol Hill.

Cassiday’s Capitol Hill career began when he obtained alcoho for two House members who had voted in favor of Prohibition and his network of clients quickly grew from there.

Developing contacts on the Hill the same way a lobbyist might, Cassiday, a liquor-filled leather briefcase in his hand and his signature emerald hat on his head, soon found himself making up to 25 deliveries a day to clients in the Senate and House Office Buildings.

Since the Capitol Police and door guards were appointed by members of Congress who were thirsty for what Cassiday was able to supply, he never had any issues gaining access to the Senate and House and it wasn’t long before he was “spending more time there than most of the representatives.”

His hooch hustling eventually became so commonplace Cassiday was given an office across the street from the Capitol in the basement of the Cannon House Office Building. Using a secret door knock to gain entry, member of Congress would drink and play cards in Cassiday’s office while waiting for floor votes.

“It’s not very surprising that Cassiday was able to keep so many Congressmen as clients, especially ones who voted for the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act,” Travis Spangenburg of the American Prohibition Museum told RealClearLife. “After all, one of the most successful strategies employed by the Anti-Saloon League in their pursuit of Prohibition was their ability to stock Congress with lawmakers willing to vote dry, even if they weren’t personally dry themselves.”

Cassiday was able to keep Congress wet with illegal liquor for about five years until he hit a snag and was arrested by a Capitol Police officer while delivering six quarts of whiskey to a House member.

The House Sergeant at Arms described what Cassiday was wearing during his arrest to reporters and the booze bust became known as the “Green Hat incident” and made local headlines.

After pleading guilty to possession of alcohol and being banned from House premises and his office in the Cannon Building, Cassiday shifted his base of operations to the north side of the Capitol and ran things from the Senate Office Building without disruption for almost another five years.

Although successful, Cassiday was never able to establish the same type of speakeasy he had in the Cannon Building as his new clientele, mostly Senators, would send secretaries or clerks to buy his liquor rather than coming themselves.

Though it lasted longer than most congressional careers, Cassiday’s career as a Capitol Hill bootlegger came to an end in 1930 when a sting operation run by teetotaling Prohibition Bureau agent Roger Butts, known as the “Dry Spy,” nabbed him with six bottles of gin in a Senate parking lot.

A police raid on Cassiday’s home a year before had resulted in the seizure of 266 quarts of premium liquor and the two incidents, as well as his 1925 arrest, netted the Man in the Green Hat an 18-month prison term.

Following his forced retirement, Cassiday authored a front-page series for The Washington Post prior to the 1930 midterm election. In it, Cassiday wrote he served “more Republicans than Democrats and more drys than wets” during nearly 10 years of running hooch on the hill as well as estimated he had helped four out of five lawmakers break the law. A true professional, Cassiday named no names.

Regardless, the five-article series was undoubtedly a contributing factor in the landslide Democratic victory in the midterms.

“The series of articles for The Post was remarkable. Almost no bootleggers ever came forward like this,” Garrett Peck, the author of Prohibition in Washington, D.C.: How Dry We Weren’t, told RealClearLife. “You hear all about bootlegging but you never hear of people spilling the beans on themselves. This was a national story. Everyone was really shocked by the Congressional hypocrisy.”

When he died in 1967 at the age of 74, Cassiday’s wife burned her husband’s ledger book (which Peck said would have been a “national treasure’), ensuring the names of his former clients would never see the light of day.

“Cassiday’s success is a testament to the fact that Prohibition didn’t affect those who had the wealth and connections to avoid enforcement,” Spangenburg told RCL. “After all, Cassiday served time for his business while his customers’ exact identities will remain a secret for eternity.”

The infamous bootlegger’s, however, will not and has even been immortalized by a line of booze, Green Hat Gin, which is produced as an homage to Congress’s personal bootlegger.

“George Cassiday’s great legacy is that he bootlegged for Congress for 10 years for both the Senate and the House and then spilled the beans on Congress after he got busted for the last time,” Peck said. “That heavily embarrassed Congress and helped lead to the downfall of Prohibition. He had a serious impact on repeal.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.