The autopsy, attended by police officers, was conducted neither at a hospital nor a medical examiner’s office, but at a funeral home. The man on the table was only 27. A bespectacled doctor with a high forehead examined the body and determined death had been multicausal: prone restraint, positional asphyxia and blunt force trauma about the head, neck and torso.

The death was ruled a homicide, which for Anguilla — a paradisiacal British territory east of Puerto Rico and north of Saint Martin known mostly for its pristine beaches — wasn’t completely unheard of. According to the most recent government figures, murders per year tend to fluctuate between zero and four.

That the battered man, whose body would be in a white casket surrounded by flowers a few weeks later, was allegedly killed by an American tourist, though, made it exceptional.

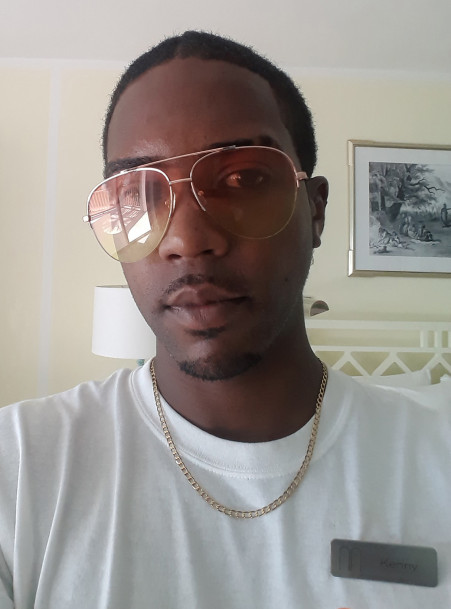

On April 13, 2019, the Royal Anguilla Police Force arrived at Malliouhana Resort, which has attracted high-end tourists since it opened in the 1980s on the island’s West End. Law enforcement had been called at 4:05 p.m to Room 49, where Gavin Scott Hapgood, 44, a financial advisor for UBS, was staying with his family. The police reportedly found blood on the floor. And it was in that room that Hapgood, who lives in Darien, Connecticut, is accused of killing Kenny Mitchel, a 27-year-old Dominican.

Four days later, the police announced that Hapgood had been arrested and charged with manslaughter. Bail was initially denied. But after a stint in Her Majesty’s Prison, the court, citing safety concerns, let Hapgood walk free on a bond equivalent to $74,000. “[T]here were persons employed at HMP who hailed from the same jurisdiction as the deceased,” wrote the judge. “The court was also informed that there were prison guards employed at HMP who were related to the deceased.” (Asked if this was true, a prison staffer told InsideHook, “Yes, Kenny has a relative who works at the prison.”)

The Hapgoods left Anguilla and returned to the United States, promising to appear in court for a hearing on August 22, 2019.

Once news leaked of the arrest and the court’s decision allowing Hapgood to leave the country, dueling stories about what happened in Room 49 began to circulate on Facebook and in both Anguillian and American media. They would bear little resemblance to each other.

According to the version told by the Hapgood camp, the family had been out, and Hapgood returned to Room 49 to use the restroom. A short while later, after his two daughters arrived back at the room, there was a knock at the door. Mitchel, clad in the hotel’s uniform, said he was there to fix a broken sink. The sink wasn’t broken, Hapgood told him — and he had not called the front desk about it — but Mitchel was welcome to take a look. Then, armed with a knife, Mitchel demanded money and attempted to rob Hapgood. The men fought. During the brawl, which was apparently witnessed by Hapgood’s daughters but not, according to a statement released by the family, his wife Kallie, Mitchel bit Hapgood’s face “multiple times.” (A Hapgood attorney confirms to InsideHook that Mrs. Hapgood was on the hotel premises, but was not in the room during the incident.) At no point, the family said, did Hapgood “choke the attacker,” but Mitchel was “restrained by a security guard.” When Hapgood was taken to the hospital to tend to his injuries, a spokesman said, “the attacker was alive and being taken away by medical staff for treatment.”

But there’s an alternative version of the story favored by Anguillians and Mitchel’s family. Mitchel, known by friends and family as Mylez, had not shown up to Room 49 unannounced, but rather had been summoned, by name. Around 4:00 p.m., a security guard and other hotel staff members entered the room and found Hapgood holding the smaller man in a chokehold, his knee in Mitchel’s back. Mitchel, as he lay under Hapgood, denied the accusation of robbery. Hotel employees tried to separate the men, but the security guard warned them not to get involved. “Stop it, stop!” Mitchel said. “He came to my room to rob me!” Hapgood replied, according to one account. (“He would never try something that dumb,” Mitchel’s brother told NBC News. “It doesn’t add up. It doesn’t make sense.”) In another account, this one given to the New York Post, a coworker said that, over the course of the 20-minute fight, the Dominican could be heard struggling to breathe — “like with liquid in his throat,” as an alleged witness put it. All the while, Hapgood kept pressure on the neck of Mitchel, who eventually died. In a radio interview, Mitchel’s father claimed the hotel staff refused to pull Hapgood off his son for fear they would “lose their job for touching a tourist.”

The diverging stories don’t entirely add up. If Mitchel wanted to burglar the room, why do so when it was occupied by the family? Why was Mitchel in the room at all? If, in fact, Hapgood asked specifically for Mitchel to come to Room 49, shouldn’t the hotel have a record of the call? If Hapgood was simply defending himself, why was it necessary to asphyxiate Mitchel? If Hapgood didn’t choke Mitchel, who did?

Unfortunately, the Royal Anguilla Police Force declines to provide an incident report or comment ahead of the August 22 hearing. “We are bound by the Attorney General not to comment,” says the RAPF spokesman. Auberge Resorts Collection, which owns Malliouhana Resort, didn’t respond to a request for an interview, so it’s not clear what job Mitchel held at the hotel, when he was hired, whether he was working the day of the fatal incident, or if he had, in fact, been called to the room.

There was pronounced anger in Anguilla and Dominica over Mitchel’s death and the perceived light treatment of Hapgood. The American, according to Dominican politician Lennox Linton, did not appear “as though he suffered any injury at all or he was attacked in any way. … Everybody is interested [in] seeing justice done and obviously concerned that the U.S. national is allowed to walk out of Anguilla.” (A photo given to the Daily Mail suggests Hapgood had, in fact, been injured on his face and chest.)

Meanwhile, an editorial in The Anguillian, the local newspaper, observed that “[i]ssues of race and wealth have immediately come to the fore while people watch keenly to see how the police will deal with the suspect. There are already claims that the suspect is not being accorded the same treatment as others in similar circumstances because of his race and socioeconomic status.”

In a series of Facebook posts — the first four days after Mitchel’s death — the Royal Anguilla Police Force attempted to diffuse anger among the islanders, who were incredulous that justice would be done.

“The RAPF would like to remind the public that: a) The defendant is entitled to a fair trial; b) There is a presumption of innocence until proven guilty,” wrote the public media relations officer on April 17. “RAPF appeals for responsible Behaviour,” he wrote two days later. “The Royal Anguilla Police Force acknowledge the fact that people want information in respect of the recent arrest and charging of a US tourist, however, like all investigation these are not conducted on social media. … The comments being made on the RAPF facebook have no foundation in fact and are likely to incite racial hatred and can prejudice a jury[,] especially since they will be chosen from among the community of Anguilla.”

That same day, the RAPF commissioner of police took to Facebook as well. “We are not shrouding the case in mystery[;] we are bound by rules and so are others on what can be said,” he wrote, and warned that justice could only be served in a court of law, “and not in social media where there are no rules.”

Local skepticism was not unreasonable. After the killing but before the arrest, the Hapgoods checked out of Malliouhana and into the Four Seasons hotel. This was viewed as a permission unlikely to be extended to the average Anguillian accused of a homicide.

But it wasn’t the presumed wealth of the Hapgoods that was the issue: tourism has long been the cornerstone of Anguilla’s economy, and visitors do not tend to be disruptive or cloistered from the locals, as they might be in countries like Jamaica. Rather, it was the perception that the legal process had been subverted. Locals feared that the Hapgoods, who could be seen on video walking to a private jet, might not come back.

A statement from the lawyer in Anguilla wasn’t quite reassuring: “[H]e has every intention to return to Anguilla to clear his name.” (In an interview, a member of Hapgood’s legal team told InsideHook, “He stands by the intentions that he’s made. Why wouldn’t he? He said it in court.”)

The lives of Scott Hapgood and Kenny Mitchel could not be more different.

Growing up in Darien as a “country club kid,” he told a reporter in 2010, Hapgood had been a good athlete. He was a member of Darien High School’s lacrosse team, and was considered by the Hartford Courant among the “players to watch.” And he was: during the 1992 season opener, Hapgood scored five goals and two assists. That same year, he set the school record for points in a single season.

Hapgood excelled at football, too, and as a tight end, routinely caught the ball for touchdowns. “He was a skinny little kid when he started, and grew each year,” says Mike Sangster, who coached the Darien team. The town, a Connecticut suburb an hour from Manhattan, took football seriously, sending its players to a sports clinic that better resembled a boot camp. They endured military exercises and speeches, along with vigorous exercise. A reporter watched Hapgood moan through 80 pushups. Sangster remembers his young receiver as “a gentleman” and an excellent football player. “When he stepped between the lines, he’d button up his chin strap and he played extremely hard.”

The athletics continued at Dartmouth College, for whom he continued to play both sports. Before a lacrosse game against Dartmouth, the University of Pennsylvania’s campus paper highlighted Hapgood, “a first team All-Ivy defensive end in football, [who] also led the country with four goals per game last season.” At graduation, he was 6’2” and 240 pounds.

By contrast, Kenny Mitchel was reportedly was 5’7” and 140 pounds. In a video shot not long before his death, Mitchel, seen dancing with his curly-haired daughter, is noticeably lithe.

There’s little online about the life of Mitchel. (Attempts to interview his family by press time were unsuccessful.) But according to a GoFundMe in his name, he and his wife both migrated to Anguilla — Kenny from Dominica and Emily from the UK. “Kenny first began living in Anguilla in 1999 and did primary school here,” emailed his friend, Stafford John. Mitchel, say Anguillian business owners, was a friend to some but known by all. The Malliouhana Resort staff took his death hard, says a pastor who went to the hotel to counsel the staff, a couple of days after the killing. He encountered grief, shock, and trauma. “This was seen as an injustice,” says the pastor. “That money — that might is right.”

A few members of the staff wondered if perhaps they could have saved Mitchel’s life.

Soon enough, proceedings will begin in an Anguillian courtroom. Hopefully the trial will shed light on the obscured circumstances of a deeply violent event. For Mitchel’s friends and family, it will be a chance for his side of the story to be told. They believe, not without some cause, that media coverage has prioritized the Hapgoods.

“Kenny left this earth forbidden and prohibited from speaking,” as a May Facebook post put it. “We will speak for Kenny, we will speak on behalf of his daughter, we will fight for justice.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.