There is no character quite as reliable as the city. Whether it’s Edward Hopper’s paintings or some television show with Chicago, Dallas, Atlanta or Miami in the title, the city is always filled with intrigue, danger and inspiration.

But there are also untold layers to every urban area. You’ll never peel them all back, because new ones are compiling at a rate that will always outpace you. Cities reinvent themselves over and over, and all we can do is stand and bear witness to it. There’s no stopping the tide of new concrete poured over what you once knew.

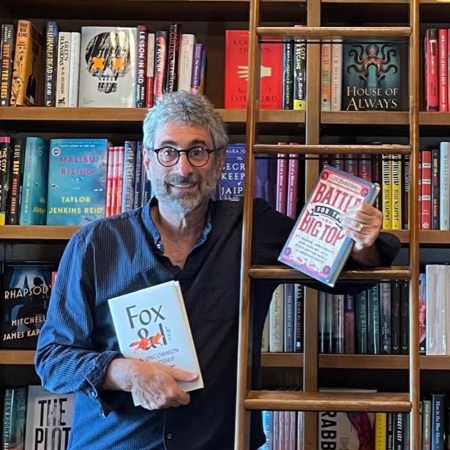

At some point, Matthew Specktor realized that. He’s held conflicting views of his hometown of Los Angeles, a place Dorothy Parker once derided as “72 suburbs in search of a city,” sometimes loving it, other periods loathing it, but all the while soaking in the good, bad and ugly of the City of Angels.

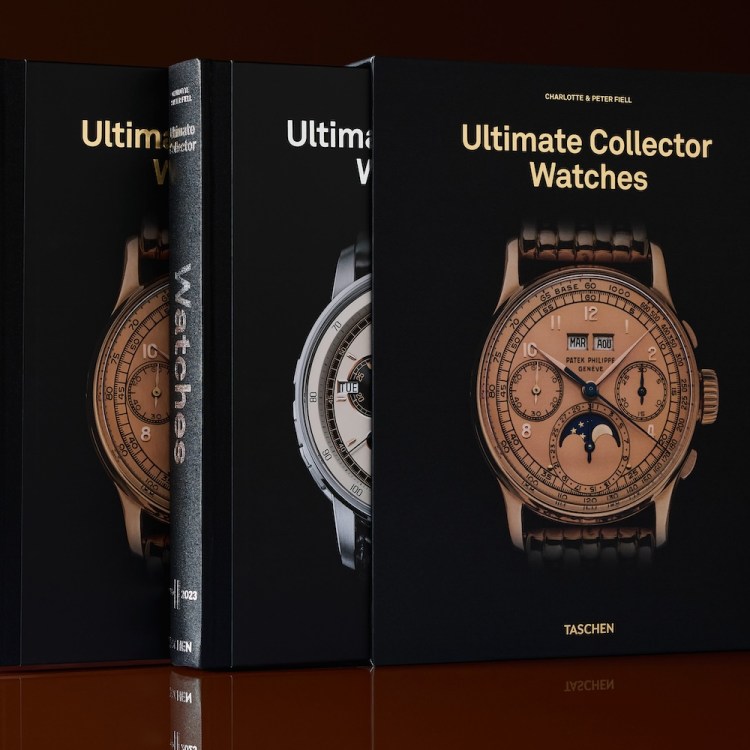

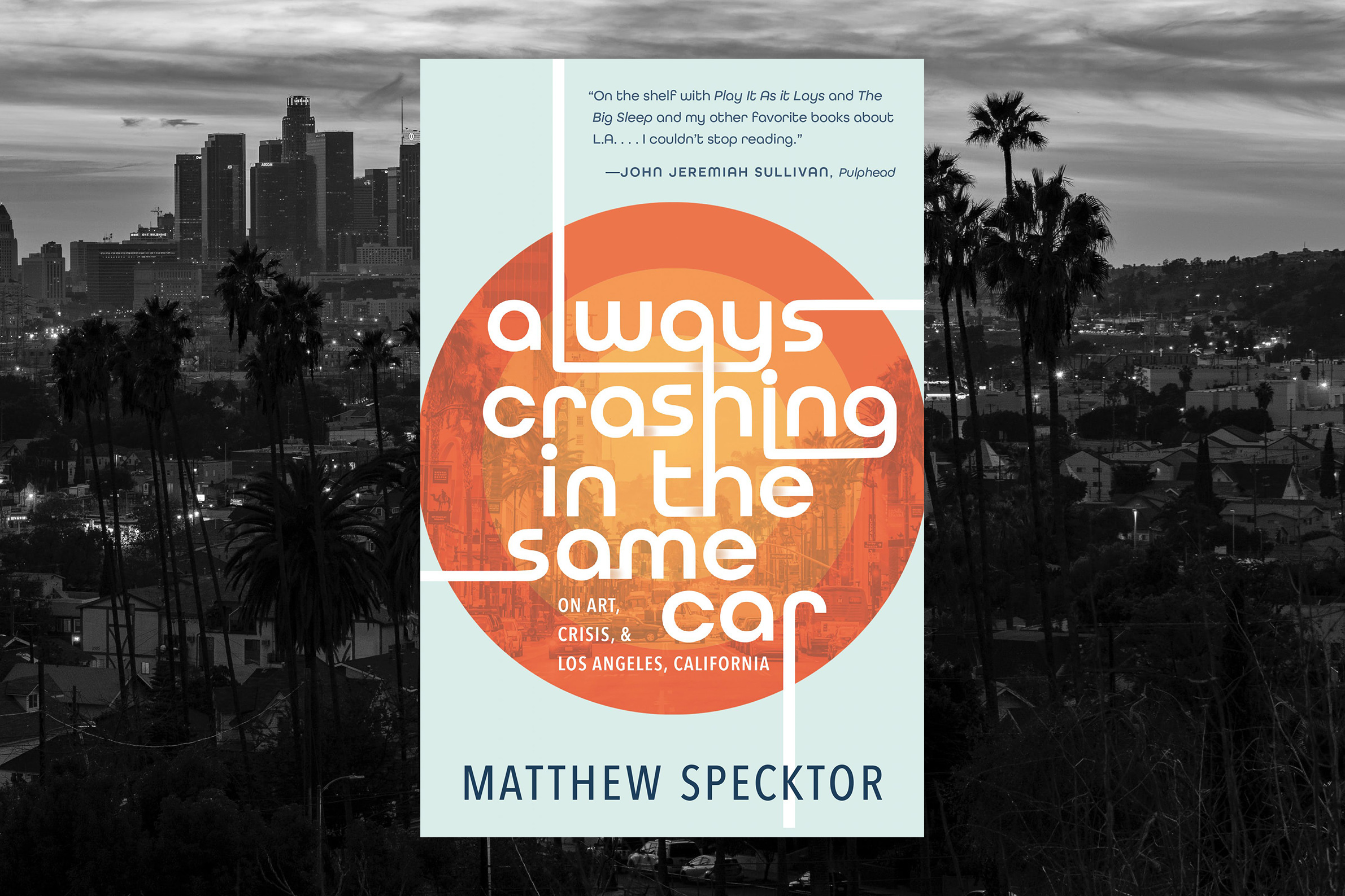

We all have to grapple with where we come from sooner or later, and how each of us do that is a deeply personal matter. Specktor decided to exorcise his demons by writing an entire book about Los Angeles, about the art and artists it has built up and sometimes doomed and how he’s learned to understand not only the place he’s from, but his life as a whole. The end result is Always Crashing in the Same Car.

It’s a history book and a work of criticism; part confession and part tribute. It’s a cultural dissertation as well as a personal one. It’s about Los Angeles, but it’s also about the writers F. Scott Fitzgerald and Renata Adler, directors like Hal Ashby and Michael Cimino, musicians like Warren Zevon, but most of all, it’s about Specktor, how he relates to these artists and how they, in turn, helped him relate to where he’s from. Each essay offers the reader a new lens through which to view the artists written about, and how the city made them or broke them.

I talked to Specktor over email about what outsiders get right and wrong about Los Angeles, NYC vs. L.A., walking, The Last Tycoon and more.

InsideHook: I know it’s probably not the best form to start off any interview in 2021 by mentioning Woody Allen, but I’ve always thought of Annie Hall and his character’s dislike of L.A. and how that sort of became this trope, that New Yorkers hate L.A. and there’s some regional competition. Now obviously I don’t believe that given the massive amount of ex-New Yorkers and children of New Yorkers and the fact that your baseball team was even from New York originally, but I’ve always wondered are New York City and L.A. just the same place filled with self-obsessed people and heavy concentrations of certain industries (film, television, news, etc.), but L.A. is just sunnier and you have to drive everywhere?

Matthew Specktor: The (mostly false) binary between the two cities has always captivated me. Woody Allen has other things to answer for, of course, but his presentation of L.A. in that movie really sucks. There might have been truth in it at the time — maybe there still is, a little — but what we’re really talking about here is a war between intellect and image. New York is the intellectual capital of America (let’s ignore for a moment the, uh, unfortunate state of this country’s education system, and of its intellectual condition in general), where Los Angeles is the nation’s funhouse mirror: the place that shows it both as it wants to be and as it actually is. The cities share a sort of narcissism — you’re a Chicago guy, you understand this; I lived in New York for the better part of a decade, and came to feel myself a New Yorker in ways I haven’t fully shaken even now — but beyond that, the differences are mostly meteorological and architectural. L.A. is spread out in a way that encourages isolation. Even before the pandemic there was a sense that everyone here is a little bubbled. But you commit to it, I think, just as you do to New York. I’ll be an Angeleno forever, even as I’m increasingly unsure I want to live here all that much longer.

You do mention at one point that when you’re stuck you get up and take a walk. Now, the belief is that you can’t walk anywhere in L.A., but I’ve actually had some great walks in that town. Is this a myth that needs to be fixed?

L.A. is roundly mocked by New Yorkers — at least certain ones I know — for being a place people take hikes. (“Am I becoming a cliche?” someone fretted to me recently, when they confessed they’d gone hiking in Griffith Park.) Hiking, of course, is walking: the difference is just the environment, and I suppose the fact that the walking is an end in itself. One hikes the canyons. One counts one’s steps, whereas in New York you can quite ordinarily wrack up 12 or 15,000 in a day without thinking about it. It’s a distinction, because even going to the grocery store here that’s three blocks from my house can leave me feeling eccentric when I don’t drive. There’s no walking culture here. Which is precisely why walking the city can be rewarding — one feels like a stranger, or like an eccentric, or like one’s experiencing it in a way it isn’t designed to be experienced. That’s a wonderful way to experience any city: it’s defamiliarizing, exciting. It gives you a sense of texture you might otherwise miss.

You “grew up, during the aftermath of the chaotic, auteurist, and fabled ‘New Hollywood’ of the 1970s,” a time that has been painted as sort of this cinematic wild west. That time, as I’ve always understood, was a pretty dark time for the city. The idea was L.A. was dangerous, smoggy, gangs of people that looked like Darby Crash roaming the streets. I know, at least in New York, there’s always this idea “This city used to be better,” but I don’t get the sense you loved L.A. back then. Am I wrong to think that? Is it the opposite for you that you like it more now?

I can’t help but think about this through the New York cinematic prism, likewise: you look back at the New York of Death Wish or Taxi Driver, and … well, every native New Yorker I know has some sentimental attachment to the bleak, nefarious-feeling city of the ’70s, the one with the graffiti-covered subway cars and all that. The Warriors. I didn’t love being a child in L.A. in the 1970s, but I doubt I would have enjoyed it any better in Philadelphia or Chicago or New York: it was being a kid (or being a teenager) I struggled with, not the place in which I happened to be one. When I was that age, I mistook the problem and thought I could outrun it, but … well, let’s just say I don’t imagine I’m the first person ever to make that mistake.

F. Scott Fitzgerald is sort of a running character in your story. Your novel called to mind some of his work and his presence is laced throughout the book, but when people think of him they think Paris or Long Island, not L.A. Which is wild since he died there and all. Had he lived to finish it, where do you think The Last Tycoon would have ranked among not only his work, but also the best works about L.A.?

I think The Last Tycoon is one of the best works about what used to be called “the motion picture colony,” but I reckon that’s slightly different. There’s a sense in which Fitzgerald really did spend those last years in Hollywood, more than he did in “L.A.” (I’m talking about his work: I know he lived in Encino, and in Malibu for a while, but Fitzgerald was addressing the movie business in his writing, far more than he was the civic apparatus and structure of Los Angeles.) “Best works about L.A.” is a difficult rubric, if only because there are so many versions and faces of the city. The L.A. of Joan Didion is different from the L.A. of Chandler, or of Steve Erickson, of Kate Braverman, of Salvador Plascencia, of Paul Beatty, of Walter Mosley, of Charles Yu, of Carolyn See, or of myself. I’m not being academic here — there’s some overlap, of course, but it goes back to that bubbled quality I referred to above. Where there’s some common agreement about what New York actually is, L.A. largely depends on who’s doing the describing. The Last Tycoon is an incredibly humane book. There’s a quality of understanding, and of suffering apprehended, that I think a lot of great literature (maybe all great literature) possesses, so I like to think it would rank fairly high. But it’s not for me to draw the structure of that canon. It would only be one more person’s opinion.

Each chapter [in your new book] is anchored by a person, be it Thomas McGuane or Hal Ashby or Warren Zevon. Was there one you felt more connected to after writing about them and yourself?

It’s a cop out to say “I felt connected to all of them,” so I won’t. Carole Eastman is, I think, the one I felt the strongest kinship with. She was such a powerfully private person, and I think — despite having just written a memoir, and being at work on another, of a very different kind — I am too. I love the strangeness of her sensibility, and the way her writing (particularly the private stuff: the letters and papers and notebooks that are held at the Harry Ransom Center in Texas) reflects this. It’s got that radical weirdness of certain 20th-century poets, like Wallace Stevens or Hart Crane or John Ashbury. I’ve got strong feelings for all of these people — McGuane is another one whose sensibility now feels fully strapped to my own, someone I’ll be in conversation with until I die — but Eastman is like my secret sharer.

A big part of the book is learning and relearning about yourself and the place you come from through the art you love. And obviously there’s no shortage of books and albums and movies about L.A., but if you had to point to one to describe your city to an outsider what would it be?

Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself. Someone described this book of mine as being like that, which is the most flattering thing I’ve ever heard. Andersen’s film (which, I’m told, is going to be a book, too: an expanded version of the film’s text and its image palette will be out next year, I think) is phenomenal: it’s both a ravishing picture of it and an incredible exploration of its psychogeography. I must have watched it a dozen times, and I feel like I’ve barely scratched its surface. What a masterpiece.

Finally, you got me to go to Musso & Frank Grill when I was in town once. I want to circle back to the first question in a way, because I feel like New Yorkers would be like, “Oh, don’t go there. It’s a tourist trap,” but I feel like 1) Musso & Frank is incredible and 2) people in L.A. seem to have more of an appreciation for older places even if they are “tourist traps.” Am I right about that?

Well, Musso’s is an institution, not a tourist trap. Hollywood Boulevard (admittedly, Musso’s is on Hollywood Boulevard) is a tourist trap. But I think Musso’s is more like … maybe it’s more like the Oyster Bar in Grand Central Station. People still go there, right? Maybe not all the time, but once in a while you do, and when you do, you feel you’re participating in something meaningful, something that’s part of the civic web. Musso’s is the same. You go there — or to the Polo Lounge, or to the bar at the Chateau Marmont or whatever — and you understand it’s not what you do every day, but it’s a way of touching down with the tradition. Of grounding yourself as a resident.

What’s the Musso & Frank go-to order?

The traditionalist would have the New York steak with green peppercorn sauce and maybe a Caesar salad, but my friend Ivy Pochoda — the wonderful novelist, whose recommendations one would be an idiot not to take — would insist upon the chopped steak, which I’m not even sure is on the menu. I’ll have that, and two martinis, even if I’m not much of a drinker anymore. Served each with a little sidecar on ice. Nice and cloudy, because something in Los Angeles really needs to be.

This article was featured in the InsideHook LA newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Southland.