“Our history has been told about men for men and by men,” says the historian Alexis Coe. “We’ve seen that when women and people of color start addressing what we consider basic history they find that we don’t know what we think we know.”

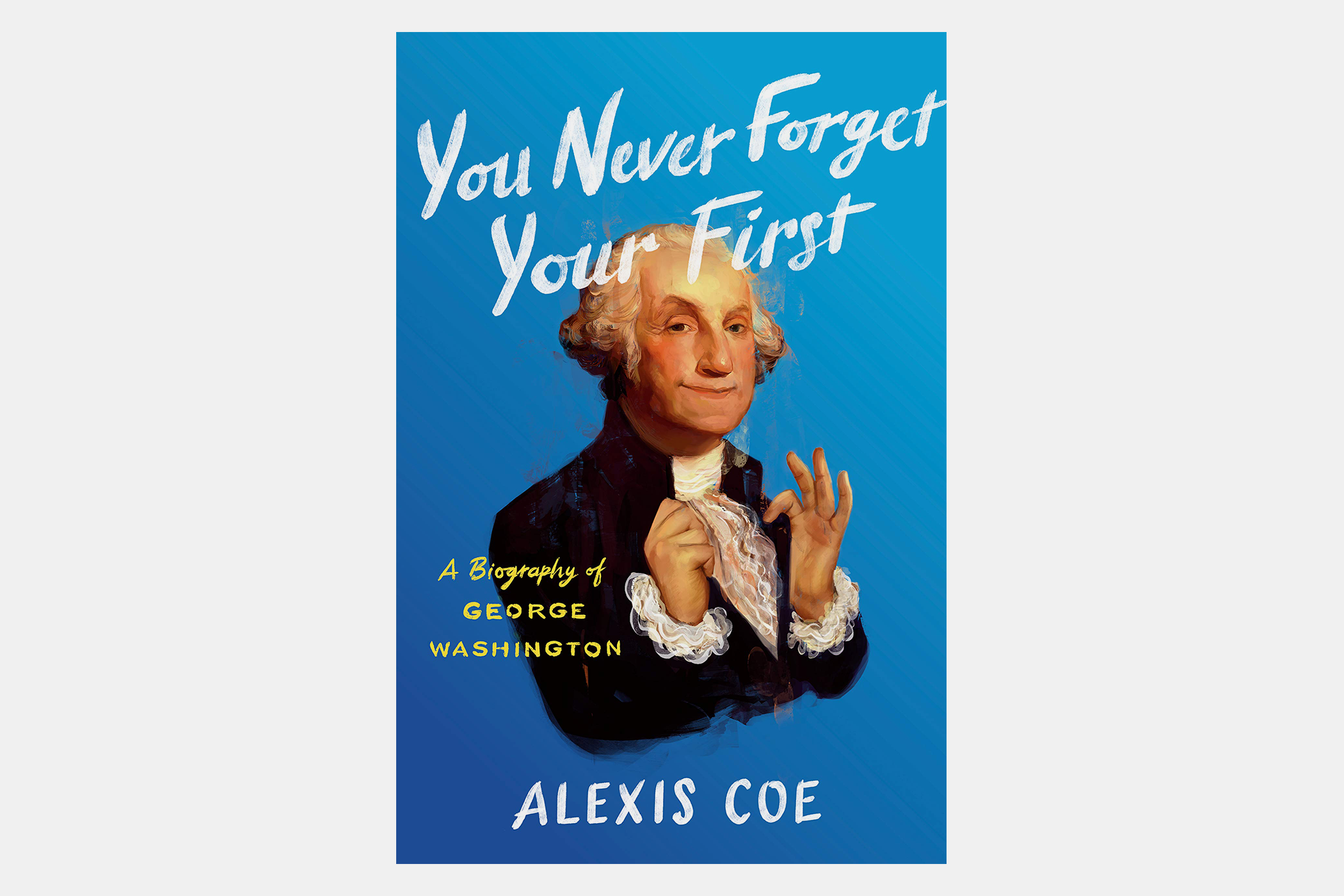

She demonstrates this deftly in her new biography of George Washington, in which she peels away at the myths surrounding the first President to reveal the many flaws of the man beneath. You Never Forget Your First is cheeky in tone, approachable and fun to read, and yet Coe is harsher on her subject than the small army of male historians who’ve written thousand-page tomes on the first president before her.

Coe doesn’t back away from the ugliest parts of humanity in her reconsideration of Washington. There are stark reminders on nearly every page of the book that Washington was a slave owner who was complicit in the genocide of Native Americans. “Historians all work in the same archives and we see the same material,” says Coe. “Why in previous Washington biographies do we hear that he was a slave master and we hear about the number of people he owned, but it’s all to serve this final beautiful moment in which he emancipates his slave? None of that is true.”

Coe is determined to share the details: that Washington once slapped a slave for not being able to singlehandedly move a tree. That he told his overseers not to beat slaves not out of the kindness of his heart, but because it behooved him to have his slaves in good physical condition. “The figurehead of American liberty was never far from a representation of its (and his own) deep-seated hypocrisy,” writes Coe in You Never Forget Your First.

Coe highlights such inequity by including, towards the end of the book, a simple yet damning recipe for hoe cakes, the meal commonly known as Washington’s favorite breakfast. “The recipe that appears in the book is mine,” she says. “It’s as good as it could possibly be. But there was a reason he loved it swimming in butter and honey.” More importantly, by describing exactly how the cakes were made, Coe wants readers to understand what mornings were like both for Washington and the people who served him. “I want people to understand that he is a slave master. So he wakes up and he is served. But the people who serve him, who make no money, who have no choice in their life, who are constantly in fear, their day starts much earlier. I wanted people to see that juxtaposition because that’s what life was like.”

The juxtaposition of great men and their evil deeds is relevant for how we talk about the Founding Fathers as a whole. Their intentions are invoked so often in modern discourse, but they’re portrayed as people who only did great things or only bad things because they didn’t know better, as if they were victims of the time they lived in. “If we understand that Washington was a man who sometimes did great things and sometimes did awful things and we have actual examples, he becomes a real person to us,” says Coe. “We’re happy that he did something at one moment and then we’re really mad at him at the next.” If we look at all of the Founding Fathers that way we’d have a good reminder that the men who created this country were not perfect.

You Never Forget Your First also delves into the quirkier side of male historians’ coverage of Washington, most notably in their weirdly sexualized descriptions of his strong thighs. Coe calls these men “thigh men” because they’re obsessed with Washington’s masculinity. “They talk about his thighs in highly sexual ways that seem inappropriate for a biographer. They’re really hot for him,” Coe points out. “So they would talk about size a lot and then they were talking about the size of his hands and you would think it was a joke but they’re being serious.” Coe believes you have to ask what’s behind the tension around his masculinity. “To me, it’s a foregone conclusion that he is masculine. He’s George fucking Washington. So why are we wasting 30 pages on how amazing and strong his body was if it’s not really furthering our understanding of him?” Coe believes that male biographers revere him too much and therefore have blindspots.”They think he’s a great man. And if you go into something thinking he’s a great man, you’re defensive and you’re never going to see other parts of his personality or admit to them.”

The flip side of the male biographers’ anxiety about Washington’s masculinity is that they aren’t curious about things off the battlefield or outside of stature. “They are disinterested in most women in early America,” Coe says. “How could you possibly understand Washington who was raised by a single mother and ignore motherhood?” Instead they focus on Washington’s father, who died when he was 10 and whom he barely knew. Washington’s father left behind very few letters and so little is known about him overall, but that’s okay with Coe. “I have very little interest in his father and his older brother either because they didn’t raise him, they weren’t there, they weren’t struggling with him. His mother was the one who was trying to feed Washington and his siblings when there was no money and no way to make money because she was a woman in early America.”

There has never been a more exciting time to be a woman historian, Coe says, but women historians need to do double duty: “We have to look at women and insert them into the narrative if they were ignored or we have to reevaluate them if they have been dismissed or belittled. And we also have to check men’s work. It’s just a fact.” She also believes that a book doesn’t need to be lengthy and dry in order to be informative, and she also gives her readers credit for their savvy. “I don’t need a story wrapped in a bow, and I don’t think readers do either. I think they’re a lot smarter than that. I think you can give them all the information and they can make their own decisions.” And as for Washington? “I’m not worried about him either,” she says. “He’s not getting canceled.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.