This story was originally published on March 17, 2021.

In December, the Cleveland Indians announced they are in the process of changing to a “non-Native American based name” from the one the MLB team has held since 1915. Earlier this month, the Cherokee Nation for the first time asked Jeep to stop using the tribe’s name on its vehicles, a practice that goes back to 1974.

But what about the motorcycle company that predates both of those cases?

As the modern reckoning with the appropriation of Native American culture picks up steam in the United States, Indian Motorcycle finds itself in a precarious position. The baseball name change in Cleveland seems to set a precedent for a similar replacement here, and the recent conversation at Jeep sets an industry precedent, both of which could move the bike company out of the periphery, where it has long lived in these conversations, and into the fray.

Indian Motorcycle touts itself as “America’s First Motorcycle Company,” a nod to its founding that predates Harley-Davidson. While the business didn’t adopt the Indian name until 1923, according to the company’s history, it did produce a line of bicycles and motorcycles using the term from almost the beginning in 1897. Today the company finds itself reinvented under Polaris, which acquired it in 2011, including a lighter focus on Native American imagery and nomenclature. But the name remains, alongside models called “Chief” and “Chieftain,” as well as the recognizable “headdress logo,” a profile of a Native American in a feathered war bonnet, which is prominently featured on some gas tanks as well as lighting elements.

“They are using Indigenous people as mascots for their motorcycles,” Cliff Matias, the founder and international president of Redrum MC, the self-described largest Indigenous motorcycle club in the country, told InsideHook. When asked if he thinks the company needs to change the name, Matias wasn’t ready to offer a definitive opinion.

“I mean, look, is Indian Motorcycle using Native Americans and a Native American image for financial gain? Absolutely,” the 57-year-old said, speaking by phone from Daytona Bike Week in Florida. “Are they giving back to Native country for that use? Not that I know of. That becomes an issue in general right there.”

Crystal Echo Hawk, the founder and executive director of IllumiNative, a group that has advocated against Native mascots, sees that issue in sharp relief.

“The use of Native names and imagery by non-Native brands, teams and organizations must stop. They continue to profit from Native mascotry,” Echo Hawk, a member of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma, said in a statement to InsideHook. “Data and research have shown that these actions are detrimental and cruel to Native peoples — especially Native youth. We urge Indian Motorcycles to stop using Native branding immediately. Native activists have made it clear that this does not celebrate or honor our people or culture. It is blatant racism and stereotyping at its worst.”

When asked if the company has ever considered a name change, a spokesperson for Indian Motorcycle gave this statement: “Since we acquired Indian Motorcycle in 2011, we have worked to honor the hallmarks of this iconic brand while respecting our riders and the communities we serve. Like any respected brand, we are actively listening, learning and connecting with all stakeholders to determine the best path forward for our brand.”

Matias did say that the company had previously reached out to get his opinion on this issue. While Indian Motorcycle declined to confirm those talks, or any potential outcomes from them, due to their confidential nature, when asked specifically if the company currently has any relationships with Native American groups or organizations, the spokesperson said, “We are committed to engaging Native American communities through advocacy and partnership.”

While Matias, who is Kichwa and Taino, was hesitant to draw a line in the sand himself, he did explain the complicated situation Indian Motorcycle presents in his club and his community. On one hand, some Native Americans have latched onto the nostalgia embodied in the heritage brand. “A lot of Natives buy Indian Motorcycles,” he said. “We’ve kind of adopted the motorcycles into our own genre, our own presence.” Others see it differently.

“There are members of the club who find it offensive, for sure. We have tribal chiefs in our club, we have famous Indigenous actors in our club, so there are pretty influential people in the club who, for some of them, it’s an issue,” Matias said. He described the situation as “a double-edged sword.”

The more positive edge is what non-Native people prefer to focus on when defending Indian Motorcycle, as well as sports mascots and other branding that relies on Native American culture. We’re celebrating them, as the line goes. But as Dr. C. Richard King, a professor at Columbia College Chicago who studies the racial politics of culture, explained, even so-called “positive” depictions can be harmful.

“I can’t speak to the word ‘Indian’ itself, but psychological studies have demonstrated that stereotypical images have negative impacts on how American Indian youth think about themselves and their communities, that even ‘positive’ stereotypes have these effects,” he said. He added that these stereotypes — like the Indian Motorcycle headdress logo — also make “dominant” groups feel better about themselves and “[activate] their stereotypes about other ethnic groups.”

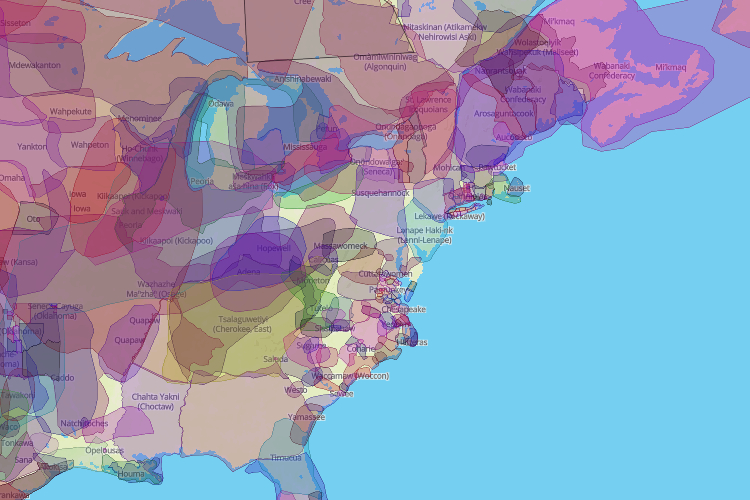

The relatively low profile of Indian Motorcycle in American society — a niche bike manufacturer versus a national football team like the Kansas City Chiefs, which is currently fielding calls for a name change — is one reason why King believes this company hasn’t been a part of the appropriation conversation, a reason echoed by Matias. But King also noted that while Chuck Hoskin, Jr., principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, had authority to ask Jeep to stop using the tribe’s name, there’s no single group that feels compelled to lay claim to words like “Indian,” “Chief” and “Chieftain” in this situation. In conducting outreach for this story, a number of tribal leaders declined to comment.

When asked if these sorts of semantic debates are a distraction from more direct instances of racism or disenfranchisement, Dr. Debra Merskin, a media studies professor at the University of Oregon whose research has looked at the stereotyping of Native Americans, responded with an emphatic “No.” She said via email that these depictions “are symptomatic of deeper problems that are economic, political, sociological, legal and otherwise that plague many Native nations.” She added that a big issue is that outsiders “are defensive when presented with the opportunity to learn why they are of concern.”

Matias, whose connection to the Indigenous community also extends to his role as cultural director of the Redhawk Native American Arts Council in New York City, has a few ideas for how to start a more productive relationship with Indian.

“I’ve had conversations with Indian Motorcycles before, they’ve asked my opinion,” he said. “But they need to continue that and also should support Indigenous causes or be at the forefront of some of the social justice issues or even just supporting Indigenous education.”

The Indian Motorcycle name goes back over a century, so the company may be more amenable to advocacy and charitable initiatives versus changing the name entirely. But as King mused, “If Quaker Oats can be compelled, after over 100 years, to retire Aunt Jemima, I would imagine that it’s possible to imagine scenarios where this motorcycle brand would change its name as well.”

Update (3/17/21): This story was updated to include a comment from IllumiNative’s Crystal Echo Hawk

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.