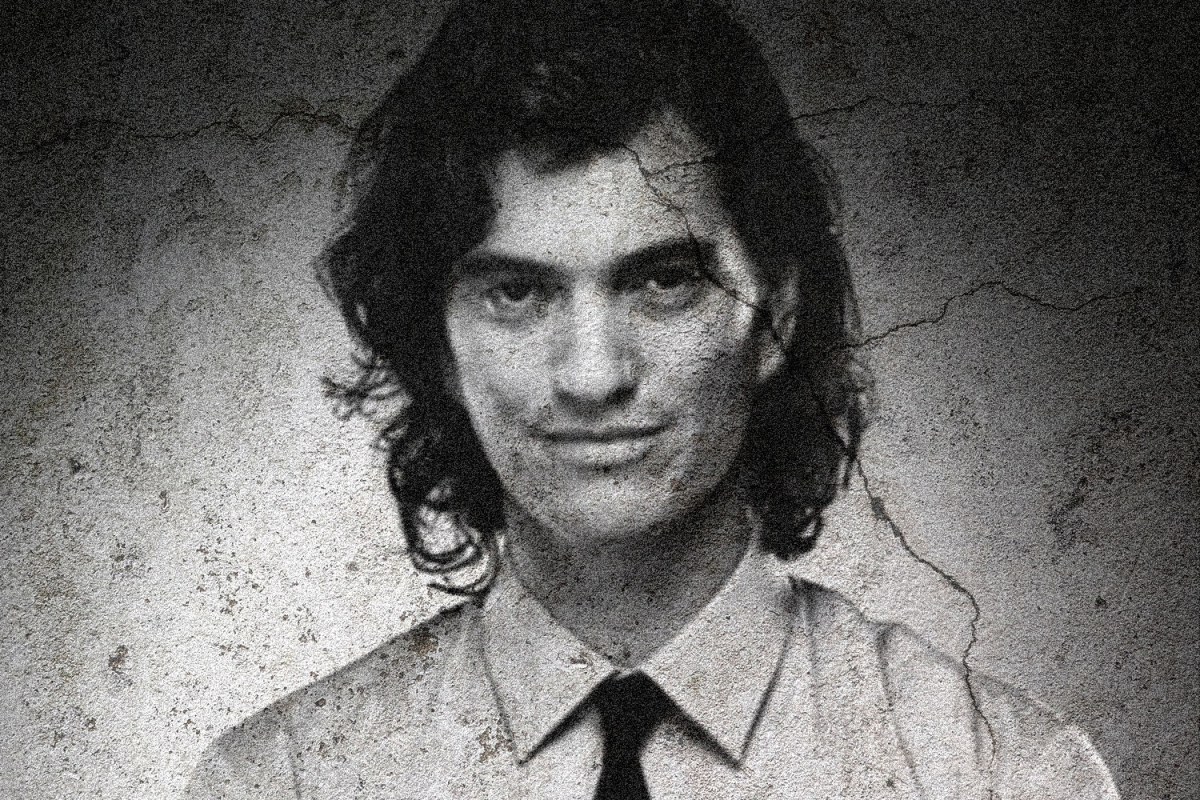

If you’re going to fail, you might as well do it spectacularly. That’s not the intended message of WeWork: Or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn, the new documentary streaming on Hulu, but it’s certainly the reason people will tune in. America does things big — cars, flat-screen TVs, meal portions — and as much as we celebrate supersized success, we’re also riveted by the self-made entrepreneurs who talk a good game, amassing millions and then, through their hubris and incompetence, flame out in momentous fashion. Part of the allure of WeWork, the company run by messianic co-founder Adam Neumann, was that, deep down, we all knew it was too good to be true — eventually, that bubble was going to burst. WeWork works a familiar narrative arc, showing how a once-promising company soared so high before coming crashing back down to earth. The predictability of that storyline is central to its appeal. There are few things more American than enjoying others’ comeuppance.

Director Jed Rothstein recounts the history of WeWork, which offered members not only a chance to have access to workspaces in hip urban environments but, also and more ambitiously, to help change the world. Those shared offices and conference rooms weren’t just for brainstorming your killer app — WeWork was meant to foster the concept of “we,” promoting the importance of empowered, selfless communities working together for the greater good. It was a touchy-feely notion, and for a while in the 2010s, it blossomed — even if naysayers like Scott Galloway, a professor of marketing at the NYU Stern School of Business, dismissed WeWork’s grandiose humanitarian aspirations as laughable. (As he puts it brusquely in WeWork, “I mean, for god’s sakes, they’re renting fucking desks.”)

But Neumann had a compelling story: Growing up in Israel and moving frequently as a boy, he spent time in a kibbutz, eventually embedding that idea of a utopian collective into WeWork’s DNA. A tall, charismatic figure with a friendly smile, Neumann sold both the company’s members and its workforce on a vision of a better tomorrow. The former employees Rothstein interviews detail the man’s skill at inspiring an almost born-again fervor among the faithful. (One former WeWork attorney admits that, to outsiders, the company seemed cultish.) Like other progressive, cutting-edge corporations such as Google, WeWork enticed young employees by flattering their sense of their own enlightened consciousness. “Millennials don’t just want a job. And they don’t just want a career,” Atlantic reporter Derek Thompson explains at one point. “They want a calling.” And while that statement is somewhat simplistic — plenty of Gen-Zers and Gen-Xers harbor similar feelings — it articulates WeWork’s one-of-us allure. Many people crave the cachet of working at a cool place and making a lot of money — but the belief that somehow your company is morally superior to its competition? Well, that’s what’s especially addictive.

It wasn’t just the employees who bought in. WeWork sleekly illustrates how Neumann’s vision enraptured Wall Street, with the company’s valuation growing bigger each year, in the process becoming a unicorn, a business term for the rare, mythic startup that achieves a $1 billion valuation. (In 2017, WeWork was valued at $20 billion. The next year, it jumped to $45 billion.) But Rothstein’s talking heads, a smart collection of reporters from Forbes and elsewhere, lay out how WeWork burned through millions of dollars without getting close to profitability, hoping no one would look behind the curtain. Whether it’s footage of WeWork’s blowout corporate parties or Neumann’s aggressive expansion into other markets — who remembers WeGrow, their attempt to remake education? — WeWork gives you all the dopamine hits you’d desire. First, we get to watch the money fly and the egos puff up. Then, we wait for the inevitable implosion.

There’s plenty of schadenfreude to savor in WeWork. Neumann’s condescending, New Age-y wife Rebekah, who began asserting a stronger influence within the company, would often brag that she was cousins with actress/influencer Gwyneth Paltrow. And there’s a particularly revealing anecdote regarding Neumann’s confusion over the difference between cappuccinos and lattes — and that no one on the payroll, including the baristas that WeWork hired at their lavish facilities, would dare correct the boss. To be fair, Neumann (who, along with Rebekah, declined to be interviewed) doesn’t come across as badly as disgraced scam-artist Billy McFarland, who in the 2019 documentary Fyre: The Greatest Party That Never Happened is portrayed as utterly without scruples. At worst, Neumann seems merely a huckster who lacked the business savvy to steer this speeding locomotive. His fate was to be one more media-appointed genius who fell for his own hype.

At about 100 minutes, WeWork doesn’t have time to get into everything. The film doesn’t mention that, in 2019, Ruby Anaya, a product manager and director of culture at the company, sued WeWork for sexual harassment and retaliation, claiming that she was fired after reporting two incidents of sexual assault. And, on the flip side, damning outtakes that show Neumann flailing while trying to shoot a corporate promotional video don’t tell the whole story: The co-founder is dyslexic, which would explain his struggles reading the cue cards. It’s a cheap shot in a film that, for the most part, takes Neumann seriously enough to appreciate why his self-actualizing mission spoke to so many people — and also why it wasn’t built to last.

In the last 20 years, we’ve seen several films about technological next big things that weren’t as great as they seemed. In Startup.com, Fyre and WeWork, there’s an inherent allure in watching people with lofty goals get close to their dream — only to have the rug ripped out from underneath them. Partly, it’s simple pettiness: It makes us feel better to see others fail. (Even in The Social Network, Mark Zuckerberg ends up friendless and unhappy.) But Rothstein won’t let us gloat because he recognizes that people’s need to embrace an Adam Neumann is symptomatic of a culture always on the hunt for new prophets. We seem to be drawn to magnetic individuals — Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Marie Kondo — who appear to have the world figured out. They’ll make us rich, they’ll make us feel better about ourselves. WeWork explores how WeWork collapsed, but it probably won’t prepare you for the next visionary whose brilliant idea captivates the world for a short time. We know unicorns don’t exist, and yet part of us wants to believe they do.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.