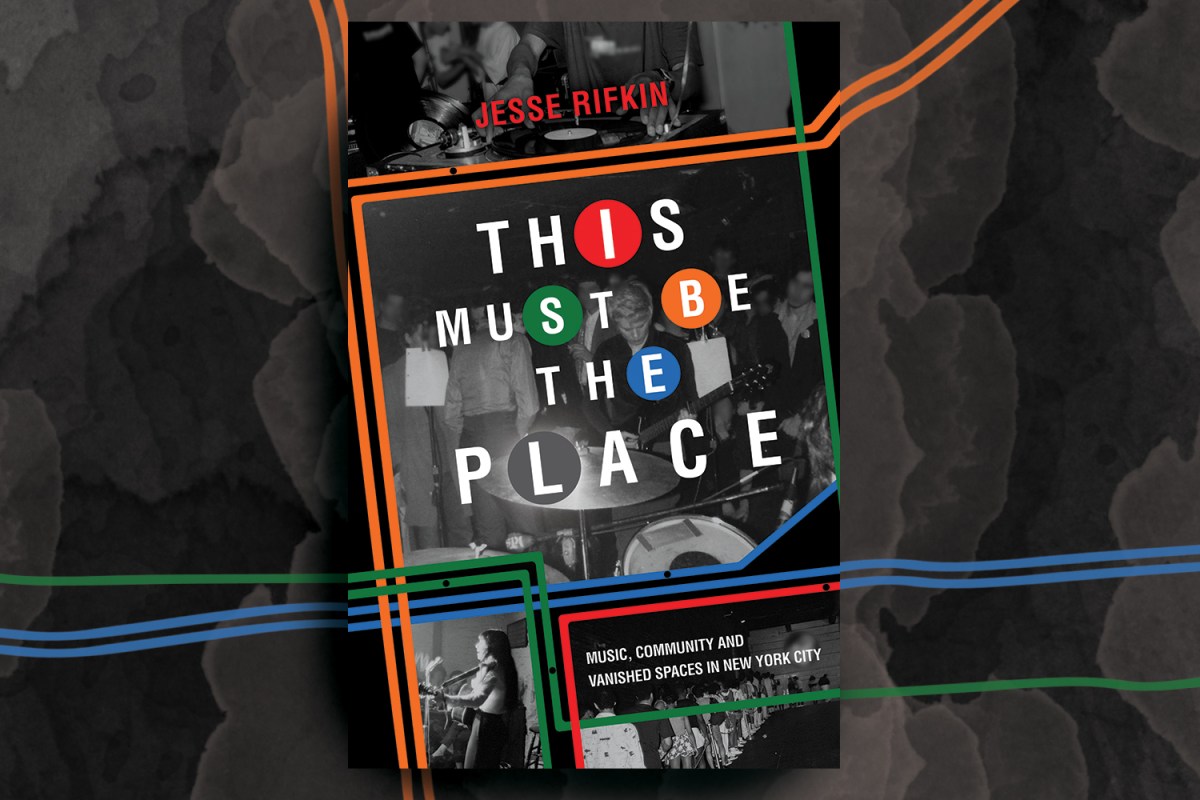

Since the middle of the 20th century, New York City has nurtured music scenes that changed the shape of the sounds we listen to. In his new book This Must Be the Place: Music, Community and Vanished Spaces in New York City, Jesse Rifkin takes a unique approach to documenting the city’s music scenes over the decades, focusing on particular spaces and the communities that flourished there.

It’s an expansive approach, and one that’s capable of incorporating everything from Max’s Kansas City to Danceteria to the DIY spaces that flourished in Williamsburg in the first decade of the 21st century. (RIP, Death by Audio.) But musical history is only one part of Rifkin’s book — there’s a surprising amount that resonated with the current moment, as live music appears to be undergoing a series of permutations in the wake of the pandemic.

InsideHook spoke with Rifkin about the process of writing such a wide-ranging history, the resurgence of cover bands and the most influential music venue you’ve (probably) never heard of.

*This interview has been edited for context.

InsideHook: How did the project of writing This Must Be the Place come about — and how did you go about figuring out what the boundaries of it were going to be?

Jesse Rifkin: That all happened very gradually, I’d say. The original idea that I had for the book was, in retrospect, an impossible book to write. I’ve read every imaginable book on music in New York and had been so fixated on all this stuff and obsessed with all this stuff forever. It was always frustrating to me to read these books that are focused on a specific genre or a specific decade or era or whatever, where it’s just like putting something behind glass or on a pedestal.

I’ve always seen all this history as a continuum, and there’s so much overlap between communities, between eras, between genres — and so much similarity between communities and eras and genres that I really wanted to put that out front. If you study all this stuff, if you look at all this history, names pop up in one place that you know from another, and venues meant to serve one community end up actually serving five communities.

The idea behind the book was to try and do something a little more broad and analytical in that way. And to maybe also expand the canon a little bit. 1970s and ’80s New York is the period that gets treated as the classic era, quintessential era of music in New York City. But you know it was important to me to include a lot of ’90s stuff, a lot of 2000s stuff to show that it’s not that it just ended when Giuliani became the mayor, but things kept going. Music — you can’t kill it — it just keeps going and going, keeps finding a way to keep going.

The original parameters that I set for the thing were that I wanted to write about venues primarily and communities, looking at it from a geographic perspective and an economic perspective. So anything that happens outside of a communal activity doesn’t really factor in so much. When a band gets famous and starts going on tour and starts making albums, you know, the inevitable side effect of that is that they disappear from their community. All of that stuff is just outside the scope of this.

By that same token, a lot of the music that comes out of the city doesn’t really come out of a community. I’ve been having this conversation with a few people recently who asked me why there isn’t more stuff about The Fugs in the book. I honestly would have wanted to have more stuff about The Fugs in the book, but they weren’t really part of a community. Even the Velvet Underground — they’re in there, but their presence in the book doesn’t match the magnitude of their influence. But again, they weren’t really part of a community.

Reading This Must Be the Place, I was especially interested in reading about the venue Tier 3, which I’d been unfamiliar with — but where, it turns out, a lot of artists I love played. How did you first learn about this space? Is there a lot of archival material about it, or did what you learned about it come from the interviews you did for the book?

I’m so glad you asked that. Tier 3 was one of my favorite things to study and write about with this book because coming into it, I had heard of it, but I really didn’t know very much about it at all. There’s not very much out there about it. It didn’t even end up making it into the book, but I know that’s where Adam Yauch first had the conversation about forming the Beastie Boys. You hear things like that or that an early New Order show in New York took place at this club. But I really didn’t know much about it. And online, there’s nothing. There was one very short article about Tier 3 online. I still haven’t been able to find any footage. There’s very few photos.

It was a pretty short-lived place, but I knew that I wanted to mention it. I knew that it was important. But then once I started interviewing people, it was really noticeable to me that every musician from that era that I talked to who wasn’t actively employed at a different club said, “Oh, Tier 3 was the best place. That was my favorite place. That’s where I went to hang out.”

Everybody from Bob Bert from Sonic Youth and members of the Bush Tetras, Elliott Sharp, all these different kinds of artists — experimental artists, rock artists. And even people who ended up opening other clubs later, like Jedi who owned The Cooler in the ’90s and ‘00s, one of his major inspirations behind The Cooler was his time at Tier 3.

It became clear to me that it was this major, major, major thing that no one had really written about. And then the real turning point there was just by accident. Hillary Jaeger, who was the booker at Tier 3, somehow the two of us connected on Instagram. She had only ever done one other interview about the club. She hadn’t really been asked; it’s not like she was turning stuff down, just no one was asking her. There wasn’t a lot of documentation.

She was really, really generous with her time and with her memories and with photos that she had. Just getting to talk to her and having her cooperate with the book and participate in the book was just such an incredible thing. One of the major photos on the cover is a photo she took of the Bush Tetras at Tier 3.

What were the challenges? Were there any particular artists or venue people or people involved with the scene who were really difficult to track down or get a conversation with?

There are definitely people that I had to write around, who did not want to participate for one reason or another. A lot of people said, “I can’t tell you anything because I’m working on my own memoir.” And then when I would talk to other people about it, they’d say, “Yeah, that memoir is never coming out.” I don’t want to name any names on the record, but it’s pretty obvious in the book who wouldn’t talk to me.

There were so many people who were so generous with their memories and with their time, that it wasn’t really as much of a hurdle as it might have otherwise been. I certainly was not hurting for information or quotes or anything like that.

How long did the overall process take? You mentioned in the acknowledgments that a few of the people you had talked to for the book died before the book had been published.

I wrote the proposal right when we went into lockdown. I sold it, and started working on the book in June of 2020. So, from stem to stern, the better part of three years.

You wrote about the pandemic’s effect on certain venues that have shuttered or opened in the wake of it. One of the points you make in the book is that CBGBs, when it first opened, was notable for not booking cover bands. As I’ve looked at a lot of venues post-pandemic is it seems like there is a significant rise in cover bands playing venues that I never expected them to play before. I am curious if you’ve noticed this as well.

I have noticed that as well. The economics there are so difficult, I think, at this point for venues, much as they were in the 1970s, like when CBGB was opening. It’s even harder now for venues to to stay open, especially venues that are legal, you know, 100% above the board legal, to take on a new thing and a cover band is a sure thing.

Generally, people seem to be more risk averse economically in that way. And the other thing you see really flourishing in clubs now is dance music. That’s the stuff that seems to be much, much healthier — because, again, the economics there were much more favorable for club owners.

There’s the point in the book where you talked with someone who said that the bar would make about a quarter of what it did on a DJ night when there were bands playing. That went a long way toward answering questions about why so many venues were emphasizing DJ nights now.

Also, if a band plays a small show at a club and they get paid $100 at the end of the night and it’s a four piece band, then that’s part of their respective car rides home, right? But if you’re a DJ and you make $100 at the end of the night, like that’s $100. It’s a lot easier, not just for the clubs, but for the artists, for the people involved. And even with dance music, you see a lot of people who are making music of their own, but their primary method of performing or disseminating that music is DJing. Because that’s where the money is.

Newport Folk Festival’s Jay Sweet on the Post-Pandemic Future of Live Music

Live music is likely to be one of the last things to return post-pandemic. But can it ever really get back to “normal”?Was there anything you learned when researching this that changed the way you thought about an artist or a venue or a genre — or broader trends within all of the above?

Oh God, so much. There was so much I didn’t know going into this, I don’t even know where to start. One of the chapters of the book is about Danceteria and then the growth of these enormous clubs that sprung up in its wake, and ultimately consolidated and corporatized a lot of the underground in the city. That culminates in the Club Kid murders, which forces a lot of things to close and a lot of things to go back underground.

Before I started working on this book, it had never occurred to me that there was any connection between Danceteria and any of that stuff. When people talk about Danceteria, they talk about it as this incredible, legendary venue — which it was, it was an extraordinary place to go. And they had all this amazing music and the people who were booking there had impeccable taste.

But it also had a lot of money behind it. It was like a bunch of clubs within one club. And they could pay performers really well. But with the side effect that if you played there, you couldn’t play anywhere else for a little while because they needed to make sure you would draw. And so all these other clubs start to close — Tier 3 closes, the Mudd Club closes, Max’s Kansas City closes at least in part because of Danceteria consolidating all of this stuff.

I definitely didn’t realize that Rudolf Piper who owned Danceteria then went on to co-own the Palladium and Tunnel and Mars, these even bigger, even better funded, more corporate clubs where by necessity, the aspect of the underground that was present at Danceteria became smaller and smaller and smaller, to the point where it can just be totally obliterated by Giuliani.

One of the things you bring up early in This Must Be the Place and return to later when writing about the North Brooklyn music scene was the idea of running a DIY space as a form of activism. In the post-pandemic space where we are now, where do you see that going?

I’ll say first that that idea of a DIY space as activism, it goes pretty far back. I talk about that as well in Chapter Two, which is all about the loft jazz venues in Soho and the minimalist venues. It’s the workers seizing the means of production for music that doesn’t really have anywhere else to go. And it happens over and over and over again. And every time that it happens, it brings something really vibrant and beautiful and uncommercial into existence. So it really is as important and as major a form of activism as any.

Where is it going? Maybe this is naive of me to think, maybe it’s Pollyanna-ish, but when I think about these DIY spaces of years past, especially in places like Soho and Tribeca and the Williamsburg waterfront, which were industrial areas, they were populated by all these factories that closed years before people just started squatting in and start illegally putting on shows and raves and what have you in these buildings.

Obviously New York hasn’t been like a manufacturing center to the degree that it was in quite some time. And so there are fewer and fewer empty factories left to colonize like that. But the major industries in the city now, or one of the major industries in the city, is the knowledge industry, the information industry, websites and tech and what have you. And all of these offices that were all over Midtown, a lot of them are empty post-COVID.

You can’t put that genie back in the bottle. People are gonna be working from home forever to some degree. And so a lot of those offices — it’s going to take time because they’re going to fight it tooth and nail — a lot of those buildings are going to empty out.

I don’t know if you’ve been to Midtown recently, but it’s fucking weird. It’s so weird now. All the businesses that served commuters are closing. There are way less Sweetgreens. And the people that are still around are really confused. The vibe there is so weird and it’s such a clearly transitional moment that I think it’s not impossible to imagine that in like 20 years, 30 years or whatever, we might be seeing experimental music and raves and what have you in these enormous office buildings in Midtown.

Those are going to be the new empty factories. It’s possible. Knock on wood. It would be awesome, right? It would be so cool.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.