Used to be Bay Area denizens flocked northwest every August to shake off their inhibitions on the Y-shaped playa of Black Rock City. Now the best of Burning Man is coming to us, right here in Oakland.

Originally commissioned by the Renwick Gallery at the Smithsonian, No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man recently opened at the Oakland Museum of California — a natural fit, given Burning Man’s deep roots in the Bay Area.

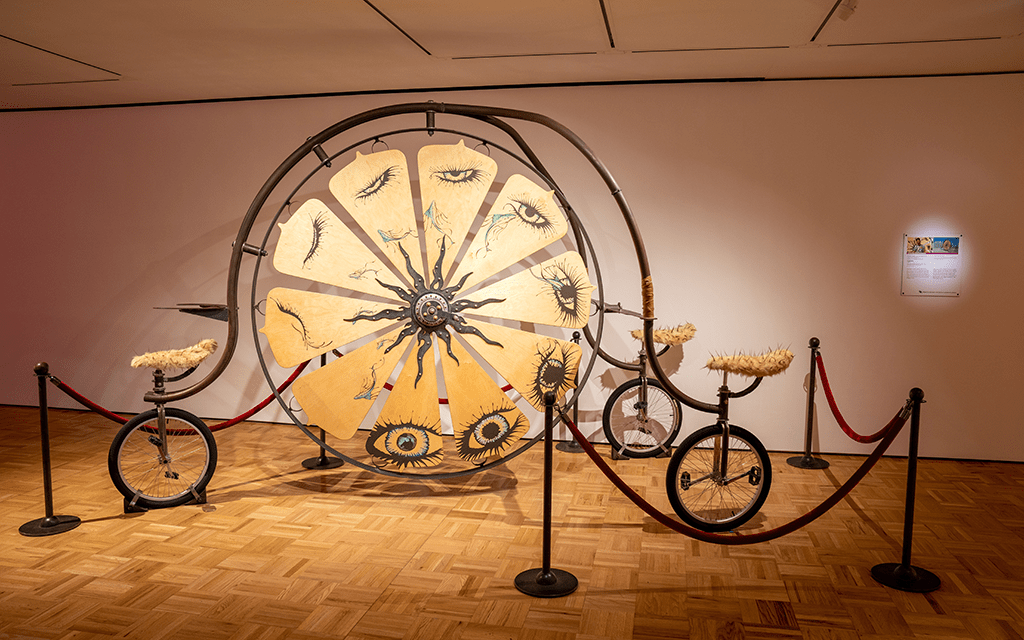

To the uninitiated, Burning Man might conjure images of every first-year art student’s back catalogue: “PVC and duct tape” projects, as Peggy Monahan, the museum’s director of content development put it. The pieces given the Smithsonian’s imprimatur, however, engage with some of the big issues of contemporary art: authorship, ownership and collaboration; devotional practices for the irreligious masses; and Burning Man staples like scale, pyrotechnics and, of course, fire. (It’s tough making art in the desert.)

If you’re in the mood to check it out, your timing couldn’t be better: this Friday, the Museum will throw a Burning Man Block Party, with some of the featured artists in attendance. If you didn’t make it to the playa, this might be your next best bet.

Below, our chat with Monahan about the exhibition and its highlights.

InsideHook: Why is this exhibition the right fit for Oakland?

Peggy Monahan: This exhibition comes to us created by the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian — it wasn’t originally intended to travel, but it just makes so much sense for us: Burning Man started here in the Bay Area, and Baker Beach. And even though the exhibition was curated by someone across the nation, so many of the artists are really our artists, from San Francisco to Oakland to Petaluma. And we have a huge and active community of Burners in our neighborhood. The other thing is that our museum and our mission really overlap with the 10 principles of Burning Man — with ideas about communal effort and participation. That’s where “no spectators” comes from.

How will local artists participate in the show?

So many of the artists are really our neighbors. For example, the Capitol Theater by the Five Ton Crane [collective] — more than 130 artists were involved in the creation of this theater on a vehicle, not just [in creating] the theater itself, but the fake candy and the concession stand and the films that play. Those folks are so local that they’re coming by to activate the piece and show off the special features of the artwork.

Is there a common thread to Burning Man art?

The artwork is actually really disparate. A lot of it, but not all, includes fire and light — it’s dark out there! We have our Shrumen Lumen from FoldHaus in San Francisco, these giant, glowing, origami mushrooms that change shape when you activate them. There’s so much that seems kind of steampunk. There’s stuff that takes advantage of size and serious scale. But then there’s stuff like the Gamelatron, which is a robotic version of a gamelan, an Indonesian instrument — maybe that doesn’t fit with those other ideas, but it totally works. It provides an experience; it creates a mood. I’d say the significant elements are participation and scale — it’s a very inviting form of art, not just in terms of people experiencing the art, but even beforehand, with people making the art. People make them often in large groups, and they’ll incorporate the ideas and visions and skills of lots of people.

Do you have a favorite example of that?

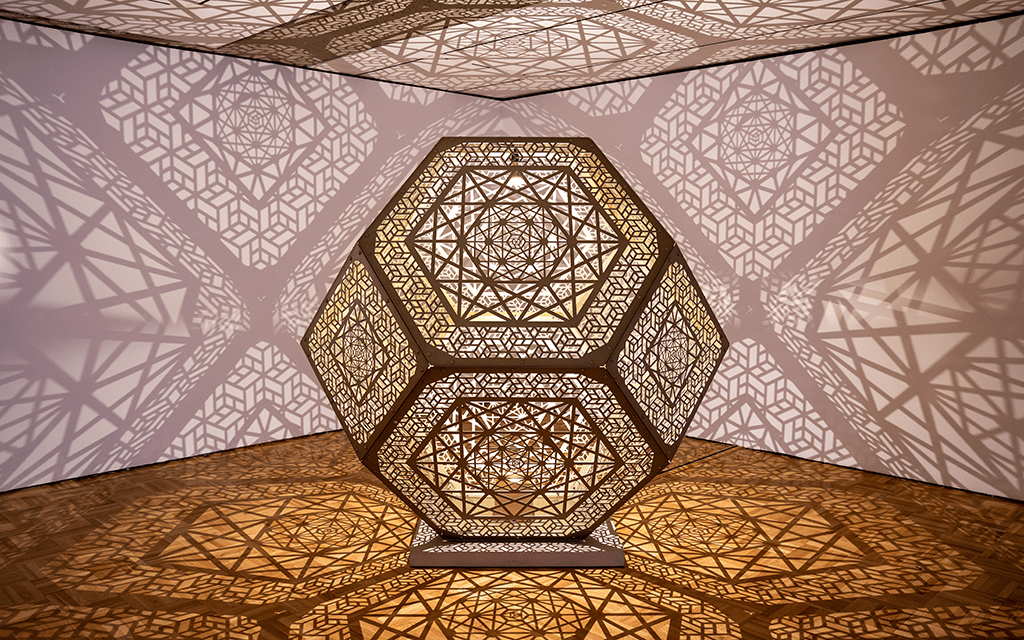

David Best created the tradition of temples at Burning Man. He works with an all-volunteer crew, with the details crafted by those volunteers. They make use of these plywood pieces, tiling them in such a way that it has an overall symmetry, but when you look closely, everything is pretty individual. For this temple, David asked them to think about someone they’d lost when working on this piece, so it was really created as the volunteers remembered someone who had died. I think people find themselves contributing to the art almost before they see themselves as artists.

Does that all-in ethos make for a lot of bad art?

I’ve had people ask me that! “Where’s all the bad art that’s usually at Burning Man? Where’s the crazy thing made out of PVC and duct tape?” These pieces are aren’t that — they’re all very sophisticated. But that said, I actually really love those other pieces, all those experiments with PVC and duct tape.

I think one of the things we do is help our community feel like they can go and make a difference with their own creativity. We wanted to capture not just that this artwork is Important with a capital I, but we also wanted to give people an opportunity to make something themselves. We worked with Rachel Sadd with “Gift-O-Matic,” this giant Willy Wonka-looking vending machine where you turn a crank and get a gift — or you can make a gift. The Gift-O-Matic focuses on the principles of gifting — which isn’t about bartering, but about gifting without expectation of return or receiving in kind.

Do you have a favorite piece in the exhibition?

Of course I love all of them, but we haven’t had a chance to talk about “Paper Arch” by Michael Garlington and Natalia Bertotti, who are based in Petaluma. It’s a large archway, covered with a sort of 3D collage. Michael and Natalia are primarily photographers, but they make these fantastic 3D sculptures that are the base for these intense collages of their photography. Since other things they’ve built have burned, this piece was commissioned by the Renwick Gallery, and it has all these photos of all these animals — it sort of explodes beyond the collage. The animals are actually taxidermy from the National Museum of Natural History — they took those pictures when they were out in D.C., talking to the Smithsonian about doing this piece. It’s striking from a distance, but as you get closer there’s more and more to see. I think you could spend a day just counting the owls.

This article was featured in the InsideHook SF newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Bay Area.