I moved to New Orleans last August, and since that day something momentous has been looming on my horizon like a live oak tree covered in Spanish moss: my first carnival season and Mardi Gras. I have been by turns excited and somewhat nervous. What I knew about it was thrilling: the parades, the parties, the costumes, the balls. But also overwhelming: an entire season marked by hundreds of events and traditions ruled by Krewes; the organizations — some over a century old, some relatively new — of New Orleans citizens who make Mardi Gras a yearly spectacle.

Fortunately, New Orleans is a great place to make friends, so I stepped out of my home to hit the streets of the French Quarter on a balmy February afternoon and get the advice of whoever had it. I needed to know what to do and see, how to dress, and — most importantly — how to behave. With our famously temperate weather and intemperate outdoor drinking culture, shoe-leather reporting has never been so much fun.

There was a wide array of opinion, but the first piece of advice I got was near-universal:

“Stake out your place to pee first,” says librarian Natalie Juneau.

“Never pass up a chance to use a bathroom,” echoes journalist Denver Nicks.

“It’s very hard to find a bathroom on Mardi Gras, so don’t stay too hydrated,” says Josephine Romo, General Manager of Cuban-inspired cocktail bar Manolito. “In fact, avoid tall drinks.”

With that first bit of solid advice, I had to figure out what I was going to do when I wasn’t running around desperately trying to find a toilet.

Konrad Kantor, co-owner of Manolito, said that while the season officially starts with the parade of the Krewe de Jeanne D’Arc in early January, he doesn’t feel like Mardi Gras is really coming until the notorious Krewe du Vieux parade winds its way through the French Quarter a couple of Saturdays before Mardi Gras. This adult-theme parade, featuring non-motorized human and mule-drawn floats, is famous for its bawdiness, political satire, and lewd floats and costumes.

It also features only brass bands — no pre-recorded music. Local trumpet player John Zarsky tells me that he spends the weeks leading up to Mardi Gras asking people at every gig he plays or attends which of the older musicians will be at which parade so he can be sure to hit all the best second lines. Many of them end up at Krewe du Vieux.

Radio Producer Betsy Shepherd says her favorite thing about all of Mardi Gras is the high-school marching bands: “Those kids got more chops than a butcher shop and moves they’ve been perfecting year-round. It’s the closest I’ll ever get to knowing what it was like to see James Brown at the Apollo or voguing at an underground New York drag ball.”

Another thing that nearly everyone warned me about was understanding the actual hours of Mardi Gras day: the revelry begins at the break of dawn, with people leaving their houses around 5 a.m. In Treme, the North Side Skull and Bones gang practices the 200 year-old tradition of dressing up like terrifying skeletons, beating drums and warning local children, still in their pajamas and rubbing the sleep from their eyes, to be good little boys and girls — or else.

“My first Mardi Gras I didn’t realize it was an early morning event,” recalls Romo. “I remember appearing at noon on my first time and seeing that the day was half over. Just take Lundi Gras [i.e., Monday, before things officially start] easy. Make your red beans and rice.”

Nicks has a different strategy: “I stay up all night on Lundi Gras, link up with a bone gang before dawn, go around dragging chains and waking up the neighborhood and then take a shot of tequila at sunrise and then go for a greasy spoon before packing it in for the day. I’m done by 9 a.m. on actual Mardi Gras.”

But Kantor has a warning about trying that method without some previous experience: “The ultimate amateur thing is thinking you’re going to stay up all night on Lundi Gras, crashing at daybreak, sleeping through Tuesday and then going out that night. Most locals are at home by six on Mardi Gras.”

For Kantor, on the actual day of Mardi Gras, “watching Zulu on Jackson Avenue is the best single thing you can do.” The Zulu parade, put on by the city’s most famous predominantly black Krewe, might be jarring for an out-of-towner or the politically correct-minded: members wear blackface and grass skirts and throw coconuts into the audience. On the same day, in the hip Bywater neighborhood, the more inclusive and less provocative St. Anne parade takes place. Konrad is clear as to why Zulu is his favorite: “This is a black city — if you’re not black here and you feel like you fit in, that means you’re not experiencing a new culture. For someone seeing Mardi Gras for the first time they should experience something they can never be a part of.”

And what should I wear? On Mardi Gras day Kantor — heavy-metal fan — wears a pair of Gorgoroth tights and a medieval tunic covered in band patches which he adds to every year. Not my style, but compelling nonetheless.

“Wear a handcrafted costume that allows you to explore a persona you normally don’t,” advises Shepherd. “Shoot for equal parts mystique, glamor and absurdism.”

“On Mardi Gras day you should absolutely wear a costume,” concurs Juneau. “Ideally one you make yourself. And while plenty of people don’t follow this rule I think avoiding popular culture is more fun and more of what you will see. Wearing a Trump or Hillary costume — even a satirical one — would just be kind of a bummer on a day like that.”

So what about Mardi Gras etiquette? Are there things one should and shouldn’t do? How do I make sure I’m not a jerk as I race from bathroom to bathroom in a rhinestone cowboy outfit catching coconuts at nine in the morning?

The Throws — little gifts, tchotchkes and beads parades throw to onlookers, seem to be a big point of unspoken decorum.

“Once the beads hit the ground,” says Romo. “You can’t touch them anymore.”

“Is that some kind of tradition about not having caught them?”

“Yes,” she replies.

“Also, this city ain’t known for its sanitation,” chirps someone at the end of the bar.

“No throw is ever worth fighting over,” adds Juneau. “Even if it really stings when a drunk fratboy army grabs that Muses shoe from your Aunt.”

A unanimous and universal code I was told: always give your throws — especially any toys — to a cute kid if there is one near.

Shepherd elaborates on these shared understandings: “Because of the extremely indulgent nature of Mardi Gras, you gotta throw in extra doses of politeness at every turn. Mobs and mobs of intoxicated people are able to celebrate carnival together in nearly lawless, overcrowded streets only because there is an unspoken and inviolable social contract of supreme niceness. Without that, things would devolve pretty quickly and sometimes do. It’s the golden rule of Dionysus: treat your neighbor to any booze and drugs with which ye wish to be treated.”

“Do not get arrested,” warns Juneau, “or you will be held in the chokey until Ash Wednesday due to all the police being on parade detail and all the judges being in the parades.”

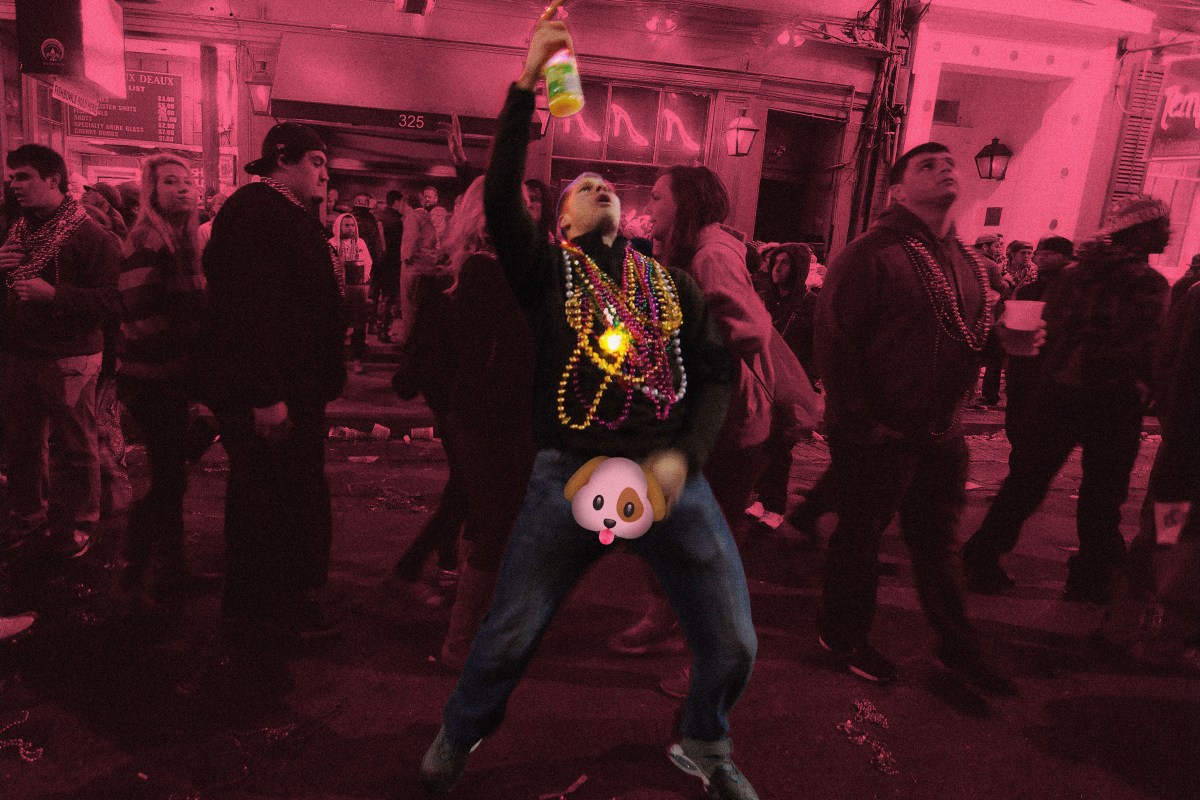

“Also,” says Nicks, “girls flashing their boobs is not really a thing. I mean, you can if you want. But it’s not a thing people do except on Bourbon Street I guess, which isn’t a real place.”

And the worst thing they’ve ever seen on Mardi Gras?

“I saw a dude try to go down on his girlfriend on the sidewalk of Dumaine Street right after the Krewe du Vieux parade. They were extremely drunk and really going all out. Everyone was standing around and literally cringing until a large older man approached them and pulled them off each other like a vet might pull puppies away.”

“There’s a Krewe that comes through the Quarter the week before Mardi Gras and they decorate their float with trash,” recalls Romo. “And last year their hand-built nasty gutter punk toilet — it was basically a bucket — broke down next door [to the bar] and stayed there for three days.”

Not to be outdone, Shepherd recounts a story combining the two aforementioned horrors: “I saw people making out in a port-a-potty. No smooch session should ever take place that close to raw sewage, but as a bonus cringe factor, the port-a-potty company was called Pooh Dat, a pun on the Saints’ ‘Who Dat?’”

The final piece of advice everyone gave was to avoid Bourbon street — with a few exceptions:

“On Mardi Gras morning the locals take over Bourbon Street,” explains Kantor.

“Even Bourbon Street, in the right part of it at the right time, can be pretty fun,” agrees Juneau.

“Bourbon street is mayhem,” asserts Nicks. “Except at midnight on Mardi Gras day, after everything. It’s kind of cool to watch the police horses walk up the street clearing it out. It’s the ceremonial end to the whole shebang.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.