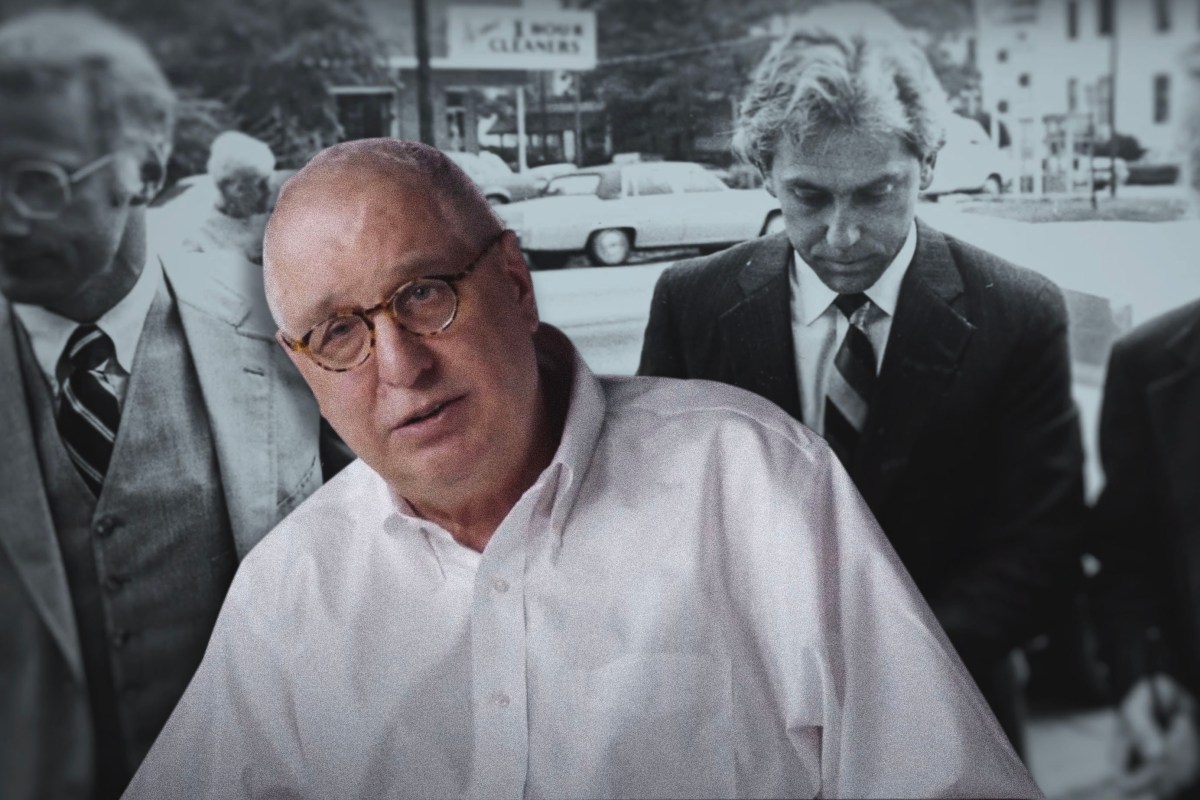

A Wilderness of Error begins with a documentarian. Filmmaker and author Errol Morris recounts his first tangible encounter with the Jeffrey MacDonald murder case. One Christmas day, Morris and his wife visited the housing unit at 544 Castle Drive that had for years been dusted, toured, boarded up and recreated by so many strangers. As those who passed through its walls testify, the home was eerily preserved for almost a decade and a half. The dishes were still in the sink, the valentine cards untouched, the word “PIG” written by finger and inked in blood still visible. Years before Morris would write his contemporary true crime classic on the MacDonald case, when he was still resisting the pull of the murder’s tangled narratives, and years before the house was finally razed to clear ground for new development, Morris and his wife stood in front of the house and wondered at the secrets that it held.

In FX’s A Wilderness of Error, adapted from Morris’s book and the latest docuseries from producer and director Marc Smerling, 544 Castle Drive comes alive again — the story that began the morning of February 17, 1970, in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, when military policemen responded to a domestic disturbance call made from the residence. MPs found a harrowing scene in each of the three bedrooms. Colette MacDonald and her two young daughters, Kimberley and Kristen, were savagely murdered. Her husband, Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald, was injured but breathing. MacDonald claims a band of hippies broke into his home and authored the violence, but the hippies left no evidence of their presence.

The five-part docuseries tracks the fallout from that night: there are interviews lead by detectives from the Fort Bragg CID office, an Article 32 hearing, an appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, a crusading father-in-law, a murder trial, and a confounding suspect or two. There are appeals, more appeals, and miles worth of transcripts, an episode of 60 Minutes, a best-selling book, a hugely successful television miniseries, and too many other depictions to list. In the first episode, the weary former MP Ken Mica says, “I’ve done interviews for 20/20, BBC, Unsolved Mysteries, and other things … I’m just very hesitant to talk to people about the case.”

The story of this case has been told and retold. But for Smerling, like Morris before him, the MacDonald case is fascinating for the Rashomon quality of its facts. The evidence has been detailed, scrutinized and made to fit conflicting theories. One way the show visualizes this is with the credit sequence, which tracks a shifting amalgam of TV sets, guiding viewers through twisting and shifting media coverage. Every retelling, like every interview and investigation, exposes another storyteller, another point of view that throws the evidence into flux. InsideHook interviewed Smerling leading up to the premiere to contextualize the series in the tangle of stories about MacDonald.

A Wilderness of Error is not a single story but a constellation of storytelling. There’s no all-knowing narrator; instead, there are interviews, phone recordings, and trial transcripts to transport viewers to the case’s crucial moments. Recordings, both private and public, serve as a kind of secret oral history. The scope is so expansive that Smerling partnered with Sony Music Entertainment to create a companion podcast about the relationship between MacDonald and author Joe McGinniss, and the journalistic implications of their messy feud. The reenactments, too, are subtle works, focusing on details, movement and location. “You can’t see the different angles on certain events without telling the story over images,” Smerling tells InsideHook, but he is always looking for ways to tell the audience, “you’re watching something that has been created.” The reenactments show viewers how it could have been, according to those connected to the case, not an unvarnished truth.

Smerling and his production team approach the rest of the material with equal consideration, inviting viewers into — if not skepticism — a critical approach to the threads within competing narratives. Early on, we see a clapboard, hear a producer asking questions off-screen, and see some of the scaffolding that identifies the docuseries as part of, not apart from, the web of storytelling that is the Jeffrey MacDonald case.

When asked what drew him to the case, Smerling talks about his longtime interest in true crime and his admiration of Morris, but I think it comes down to a question that is central to this retelling: “Where does reality meet the storyteller?” he asks. The audience plays a role in the answer too, and Smerling is upfront about wanting critical and alert viewers. A Wilderness aspires to bring the spectator into an active role. “I’m asking you to look at Errol’s storytelling, to look at [author of Fatal Vision] Joe McGinniss’s storytelling, to look at [suspect] Helena Stokely’s, [prosecutor] Jim Blackburn’s, and [defense attorney] Wade Smith’s storytelling. Everybody should be analyzed to see whether their stories meet reality. And that goes for me too.”

When you’re a documentary storyteller, there’s no way to get out of making choices — you have to edit the material, exclude certain parts, organize it into a sequence. But Smerling is clear when discussing the ethics of documentary. He refers to a “covenant,” a holy pact between creators and consumers of nonfiction: “There’s a way to be expansive in the storytelling without trying to push the viewer in any direction. What you’re trying to do is present everything you think is important to tell the story, but you’re asking viewers to do the work of deciding for themselves.”

You “break the covenant” when you do one of two things: “When you trick the viewer into doing something, thinking something, feeling something,” though Smerling allows that there is room to make the experience suspenseful, or when you “tell the audience what to think.” Here he is adamant: “You can’t bend the truth to yourself or your own views to such an extent that you’ve told the audience what to think.”

The series does not simply recreate the argumentation of the book from which it takes its name. A Wilderness is an adaptation because it takes up Morris’s central questions, about how “facts come to serve the story and not the other way around,” about what happens when narrative becomes entrenched and “overwhelms the evidence,” and its ethos to always “test” stories against reality. The messiness of the MacDonald case is what keeps it out of reach of definite truth and what keeps people coming back to its boxes of evidence. Episode two of the series features a polygraph test administered to a key suspect who may be the near-mythical woman in the floppy hat cited by MacDonald in his account of that bloody morning in 1970. In step with the rest of the series, the results of the polygraph are inconclusive and unsatisfying. It would be too easy if a single instrument could settle the facts of this case.

Near the end of Morris’s book, he asks himself questions about the case’s meaning, the kind of existential musing brought on by too many hours spent dialing cold calls, reading brittle transcripts, interviewing old men with faltering memories.

“What does this case mean? What is it about? Is it about the failure of our institutions? Of our courts, prosecutors, and investigators? Is it about how we trick ourselves into believing that we know something? … About how we pick one narrative rather than another — for whatever reason — and the rest becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy?”

The docuseries does not offer definitive answers to Morris’s questions, but it continues to pose them. A Wilderness revives and reframes questions about entrenched narratives, and what truths can or can’t be known, with the texture of salvaged recordings, uncovered interviews and firsthand accounts. It opens a map to the MacDonald case, for viewers to explore and begin to answer for ourselves. The self-awareness with which the series advances stems from one of Smerling’s guiding questions, “Where does the storyteller find himself when it comes to true crime?” Hidden under that question, though, is another: What is the relation of the viewer, reader or listener to storytelling in true crime?

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.