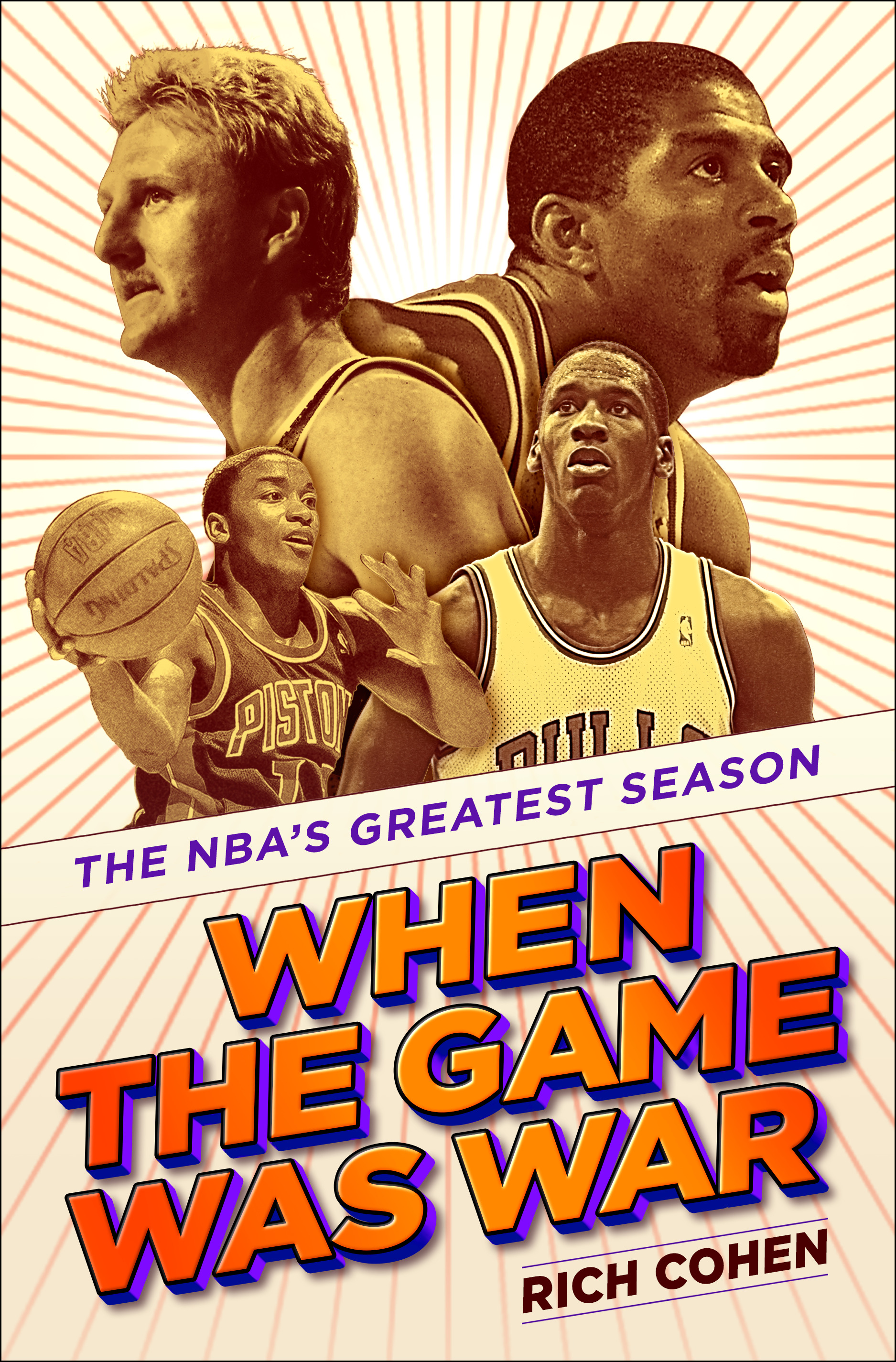

In When the Game Was War: The NBA’s Greatest Season, New York Times bestselling author Rich Cohen takes readers back to the golden era of NBA basketball when Larry Bird and the Boston Celtics, Isiah Thomas and the Detroit Pistons, Magic Johnson and the Los Angeles Lakers and Michael Jordan and his Chicago Bulls were all vying to be crowned champions of the 1987–88 season. In this excerpt, Cohen shines the spotlight on the least-heralded player in that group, Thomas.

For a Chicago sports fan in the early 1980s, life was pain. The Cubs had not won a World Series since 1908. The White Sox had not won since 1917, and, what’s worse, the last time they should’ve won, in 1919, they took money to throw the games instead, shrouding the entire city in shame. The Blackhawks had not won the Stanley Cup since 1961—seven years before I was born. True, the Bears won the Super Bowl in 1986, which was incredible— but only for a moment, as, over the next few years, we had to sit on our hands and watch as the McCaskeys, the family that owns the Bears, dismantled the team, possibly because they’d realized losing can be more profitable than winning.

And so, for much of my childhood, I focused my attention on amateur basketball. DePaul had a great team in the 1980s, a team stacked with future NBA stars. The Loyola Ramblers were good. Even the Northwestern Wildcats were interesting. But the best games were played at the high school level—not my high school, New Trier, which was constantly being outjumped and outmuscled, but the great downtown public and Catholic school teams of the era.

There were dozens of basketball powerhouses in the city: Westinghouse, where Mark Aguirre and Hersey Hawkins played; Simeon, the alma mater of Derrick Rose and Ben Wilson; Carver, which had been put on the map by Cazzie Russell. There were also far-flung Catholic schools, such as St. Joseph’s in Westchester, Illinois, where coach Gene Pingatore built a powerhouse team around the teenage Isiah Thomas in 1978.

My father would drive us to gyms across the state to watch the best teams compete. Dull fluorescent light, linoleum, flickering numbers on rickety scoreboards, cheerleaders and uniforms and freaked-out parents, my father instructing, whispering in my ear—“See how he boxes the man out? Notice how he always goes to his right? The kid can’t play with his left hand”—top prospects showing off for the scouts, who, even if you couldn’t see them, were always there. That’s what I remember.

I saw Isiah Thomas play against Westinghouse in December 1978. It was dark at 5:00 p.m. and bitterly cold. Even then, amid high school teammates and opponents, most of whom would go on to lead ordinary adult lives, Isiah looked small, fragile. On many plays, he was shadowed by two or three defenders who hung over him like oak trees, which did not matter when Isiah decided he was going to the basket. His height, or lack of, made him a lodestar for every undersized would-be in Chicagoland. He was electric that evening, scoring from inside and out, and securing the win on the last shot. The smooth efficiency of his style made you want to find something, anything, you could do half as well.

Though everyone in Northern Illinois knew about Isiah, he did not yet exist to the rest of the world. He was a secret we knew we’d have only for a little while, and it made us proud. A memory of the adolescent Isiah is also a memory of childhood, which is what made it so painful when Michael Jordan turned Zeke into a foil, and when Zeke, who’d been Daniel in the lions’ den, went from hero to antihero.

You could watch Isiah and a dozen other local standouts mix it up on the city playgrounds most weekend afternoons. The courts were gritty, the neighborhoods run-down, but the games, the quality of talent, were unreal. In 1970s and 1980s Chicago, the playground standouts pushed each other toward greatness, until, in the way of a local music scene — Liverpool in the 1960s, say; Seattle in the 1990s — they all seemed to emerge on the national map at once. You recognized them by their style. It was a Chicago style, created by the realities of the city. It was, according to Isiah, characterized by hard, physical play—not because Chicago is tough, but because the weather is so nasty. They played all winter on the West Side, which meant wind and snow. Even the prettiest shot won’t fall when a gale-force wind is blowing. Even the most eagle-eyed playmaker won’t deliver when the flurries swirl. To be effective in February, you learned to keep opponents off-balance and take the ball to the hoop; the wind can’t spoil a dunk. It was a stingy style that could once be seen across the NBA. The 1988 All-Star Game featured a half dozen players who’d grown up on the West Side courts, including Mark Aguirre, Mo Cheeks, Doc Rivers, and Isiah Thomas.

Of course, Chicagoans, though happy to serve as a talent pool, wanted a great NBA team of their own. The city had had a star-crossed relationship with the pro game. Several teams had come and gone since the first professional league was founded in 1898. There’d been the Chicago Bruins of the American Basketball League, the American Gears of the National Basketball League, and the Chicago Zephyrs of the National Association. The Bulls, a 1966 expansion club, were meant to fill a hole left by the Zephyrs, who moved first to Baltimore, then to Washington, where they play as the Wizards.

The Bulls posted a few decent seasons in the 1970s, then collapsed. They were a joke by the early 1980s, known mostly for blown draft picks and head-case flameouts. Quintin Dailey, drafted in the first round in 1982, is remembered less for how he played than for something he did on the road in 1985. Pulled from a game early, he sent a ball boy for a slice of pizza, nachos, popcorn, and a soda, which he ate on the bench.

This finally began to change in 1984, with the coming of Michael Jordan. Watching Jordan, especially when he was young and seemingly made of springs, was amazing, but it was also painful watching what happened to Isiah, and his reputation, in the process. Jordan battled Isiah as the Bulls battled the Pistons, and Isiah, in whose presence Chicagoans used to quote scripture, became hated in the process. Because of the ruthless way his team played – these were the Pistons of Rodman and Laimbeer, the Bad Boys – but also because he stood in the of the collective dream, which had appeared in the form of Michael Jordan.

The bitter struggle with the Bad Boys became part of Jordan’s legend, turning the Pistons into villains. For Isiah, it’s a bum rap cemented for another generation by ESPN’s The Last Dance, which cast Isiah as the Eternal Foe. What happened to Isiah is like what happened to the Jews when Rome converted to Christianity. What had been a local rivalry between sects—one side of the story—was canonized into an immortal battle between good and evil.

But I remember it differently. Because I was there. Because I saw Isiah play in high school and college. Because I understood what he faced in Detroit, how he sublimated his talent to turn that team into champs.

“Isiah was prickly, but he really was the best,” sports writing legend Ira Berkow told me. “I saw him score 24 points in the fourth quarter against the Knicks at the Garden, then, with the game on the line, go up and reject Patrick Ewing who was like ten feet taller than Isiah, who was maybe five-ten but could dunk like it was nothing. He had what in Chicago we call ‘the hops.’ ”

An Agave Expert Explains the Terroir of Michael Jordan’s Cincoro Tequila

Cincoro’s portfolio boasts four award-winning tequila expressions: blanco, reposado, añejo and extra añejoConsider me as one engaged in revisionist history. It’s not that I wish to devalue Michael Jordan or Magic Johnson or Larry Bird, the great players of the era, but that I aim to return Isiah Thomas to the pantheon, where he belongs.

The Athletic’s 2022 list of the NBA’s all-time best has Jordan ranked first, followed by LeBron James and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Magic is five. Bird is seven. Isiah is ranked twenty-sixth, behind Jerry West and John Stockton. I don’t think that’s right. To me, Isiah, based not on numbers but on results, on blood and guts, what he did on the floor for his team, deserves to be much higher. The third quarter of Game 6 of the 1988 NBA Finals (he scored 25 points in the third quarter on a close-to-busted ankle) alone should put him in the top fifteen. His ability to lead, sublimate and rise to the occasion — all unmatched. And the fact that he was, by some accounts, just 5’11” makes him even more impressive. A (relatively) short man in a land of giants, a Lilliputian among Gullivers, a pebble in a cement mixer. You have to be better when you are smaller. And the shorter you are, the better that better has to be. There have been many mediocre seven-footers in the NBA. Every five-footer who has cracked a starting lineup has been great. Of the seventy-five players named on The Athletic’s list, only Isiah is under six feet. Grading on the curve, Zeke was among the best of them all.

From the book WHEN THE GAME WAS WAR: The NBA’s Greatest Season by Rich Cohen. Copyright © 2023 by Tough Jews, Inc. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.