In a restroom after watching Guardians of the Galaxy in 2014, a friend of mine overheard a woman marveling over a cast so star-packed that one of its biggest names was just the voice of a computer-animated raccoon: “Bradley Cooper, he coulda been the main guy,” she mused in a New Yorky accent much-imitated in the years since. She wasn’t wrong; Cooper was a pretty big star in 2014 — bigger than actual Main Guy Chris Pratt was at the time — and he certainly coulda. Still, for many of the years leading up to Guardians, had he been cast in the lead I would have wondered why, exactly. My assessment was closer to Robert De Niro’s character in Limitless, assessing Cooper’s unexpectedly brilliant (and chemically enhanced) lead: “I’m baffled by this guy.” The preppie jag you’re rooting against marrying Rachel McAdams in Wedding Crashers — and not in the fun way that Will Arnett plays a similar bad-boyfriend heel in Hot Rod? The forgettable friend in wan comedies like Failure to Launch and Yes Man, and a smirk machine in the big-screen version of The A-Team? Even his breakthrough leading role came from The Hangover, where his character often seems actively hostile to the idea of acting getting laughs. In this context, Cooper doing surprisingly emotional and nuanced work as the voice of a talking raccoon in Guardians of the Galaxy counts as a brave defiance of expectations, not an act of lead-deferring humility. Even Limitless itself seemed to tacitly admit that Cooper would need some kind of miracle drug to reach the greatest heights of success.

Maybe he found the real-life Limitless drug, because over the past decade, Cooper has earned a passel of Oscar nominations, with more sure to come for his sophomore directorial effort Maestro, all while becoming a bigger movie star and a better actor. Whatever you think of Silver Linings Playbook, American Hustle, American Sniper, A Star is Born and Nightmare Alley, he’s giving committed, often rough-hewn performances that don’t attempt to coast on the inexplicable goodwill of The Hangover (maybe owing to a pair of sequels making sure that goodwill would be in limited supply by 2013). Do these movies and performances just seem better because Cooper is doing the classic handsome-guy move of pushing back against his good looks for cred? Maybe; I confess to a little bit of residual bafflement over the acclaim for A Star is Born and Maestro. Cooper isn’t literally limitless. But he’s undoubtedly in control as he tests his limits.

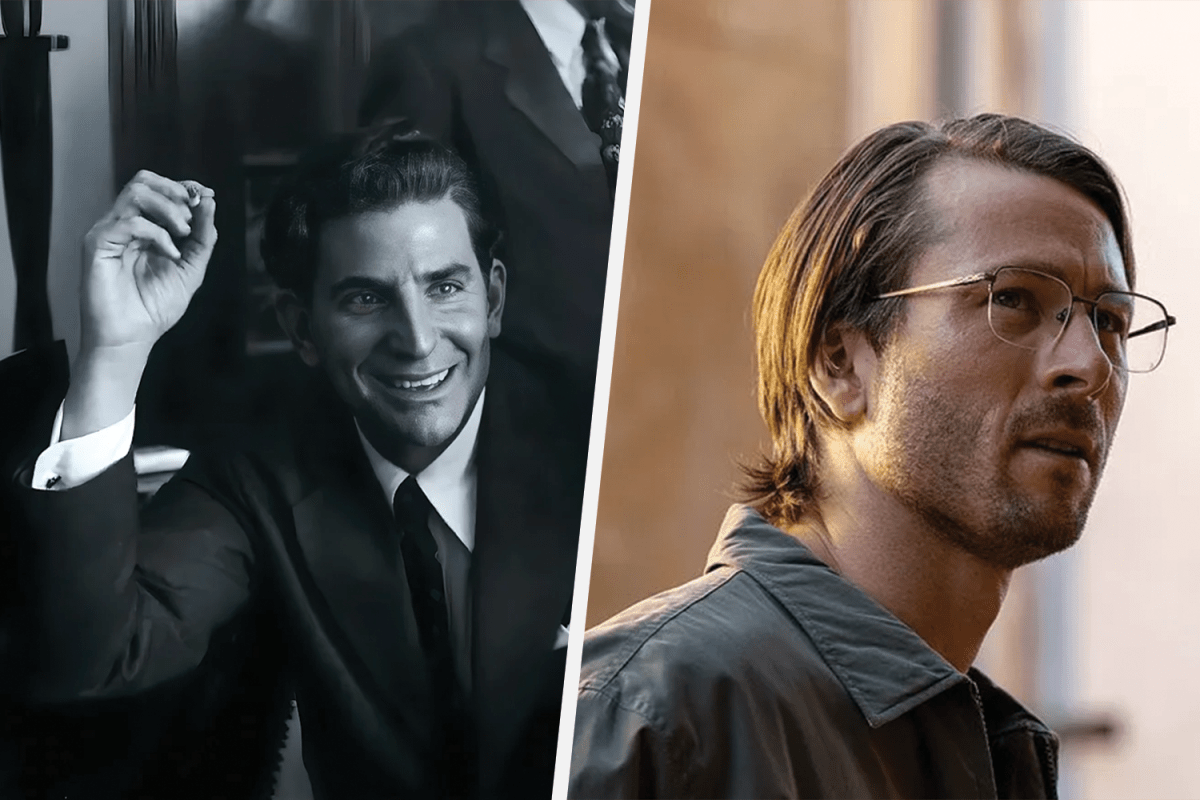

Maestro is a semi-conventional biopic of composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, viewed largely through the lens of his marriage to Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan) — though that lens must compete with the more technical kind as Cooper switches between black-and-white cinematography with a squarish aspect ratio and a wider color frame. He’s at once generous, giving much of the movie over to his co-star and allowing Mulligan some stand-out moments both introspective and Oscar-friendly, and kind of a showboat: playing Bernstein over the course of decades, attempting to balance the artist and the man, trying to get lost in the fugue of his musical passion.

Is Bradley Cooper’s Prosthetic Leonard Bernstein Nose Problematic?

Cooper, who is not Jewish, has faced criticism for donning a fake nose to play the composerIt’s those fugue-like moments that Cooper does best. When he throws himself into conducting or, in one early bravura sequence, wakes in the morning and sprints into his day with physically expressed delight, it’s like a more serious-minded flipside to the way comic mania fuels his work in American Hustle or Licorice Pizza. When he goes into A Star is Born mode, marinating in a great artist’s weaknesses, the strenuousness starts to weigh him down. Maestro at least has the excuse of profiling a real-life artist, rather than Jackson Maine, the mumbly composite Cooper brought to life with both gravitas and self-indulgence in Star. There’s self-indulgence in something like Licorice Pizza, too; his whole role in that movie is a kind of double-reverse false modesty, taking a small part designed to be remembered for its outré bad-boy unpredictability. The difference, I think, is in whether he’s indulging an amped-up caricature of movie-star charisma, or sweating his ability to be seen as an artiste. (Maybe that’s why he was so good in American Sniper: his movie-star swagger had the frailties of a man, not a genius.)

A lot of Maestro lands between the ecstasy of artistic expression and the dutiful seriousness of a troubled-marriage picture; after a certain point (and the movie feels about 20 minutes longer than it really is), there’s a lot of Bernstein taking advantage of his wife’s understanding via his dalliances with men. A solid hour-plus, in other words, of “oohhh, she’s not gonna like that” punctuated by poor Felicia, indeed, not liking it, toggling between coiled disappointment and more demonstrative confrontations. The SAG-AFTRA strike prevented Cooper and Mulligan from showing up at the New York Film Festival for a press conference following their film, and though it shouldn’t have made much difference, there was a sense of deflation, as if the movie exists largely for its stars to talk about the arduous ardor they felt making it.

Cooper isn’t the only blandly handsome leading man to try writing his own ticket with a movie that recently played the NYFF. Glen Powell, a performer so generic that I’ve forgotten his name twice while writing this piece, not only stars in Richard Linklater’s Hit Man, but co-wrote it with his director. They seem like an odd match, though they previously worked together on Linklater’s college baseball reverie Everybody Wants Some!! and his animated Apollo 10 ½. In the years since, Powell has been tipped as a great movie star in waiting, the kind of 1000-watt bulb Hollywood doesn’t produce with the same regularity as it did in decades past. In movies like Set It Up and Top Gun: Maverick, he’s struck me as a bit of a stiff. (Hell, he played all-American astronaut John Glenn in Hidden Figures — a movie about the unsung mathematicians at NASA.) He has a bit of old-fashioned, gentlemanly masculinity, but without the style or wit of a Cary Grant (a tall order, granted), or the gravity of Gary Cooper.

One of the best things about Hit Man is that it seems to recognize Powell’s squareness — and kid around with it until he’s prodded into showing off the flash that was missing (perhaps intentionally) from his previous endeavors. He plays Gary Johnson, a genially dorky college professor who dresses in normcore, dotes on his cats and enjoys birding. He’s also a part-time police helper, first in tech support and then, improbably, as a substitute in minor sting operations. It turns out detail-oriented Gary can play a pretty convincing hitman; soon his alter ego Ron is meeting with prospective clients all around New Orleans and helping to bust them for hiring a contract killer. But his encounter with Maddy (Adria Arjona) hits different, and their instant connection convinces him to convince her not to hire Ron to take out her slimeball husband. Soon, Maddy and Ron are an item. At first he doesn’t want to blow his cover; quickly, he starts to revel in role-playing as a cooler, more dangerous guy.

Like Powell’s middling rom-com Set It Up, Hit Man has the kind of studio-comedy premise that’s been mostly abandoned by the legacy studios. (Also like Set It Up, it’ll eventually be on Netflix.) Despite all of the mistaken-identity trappings and farcical turns, Linklater and Powell reconfigure the story into a rumination on identity — albeit a genuinely funny, sexy and romantic one, with genuine heat between Arjona and Powell. Powell’s toggles between Gary and Ron are especially amusing because Ron doesn’t flip into a different person entirely; to some extent, even his coolness is still filtered through Gary’s steady dorkiness, presumably picking up bits and pieces of behavior observed in both media and real life, making a composite of his and other selves. (He’s not quite dancing “dark” Peter Parker in Spider-Man 3, but he doesn’t suddenly become Cary Grant, either.)

Powell isn’t really famous enough for Hit Man to function as a proper star text, but it does often come across as a rebuke to the idea that today’s younger male stars aren’t up to job of replacing Tom Cruise, Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hanks and so on. In other words, who says these identities are cast in stone? Powell seemed most at home playing preppy facsimiles of adulthood, like those earlier Bradley Cooper roles gone ramrod straight; in Hit Man, he makes that quality oddly winning, then creates something even odder out of it. Cooper, meanwhile, feels starriest when he’s at his most unhinged. Both actors fall somewhere between the unchanging persona of a classic movie star and the transformations of a true virtuoso, making them oddly relatable after some years of buttoned-up remove. After all, that middle ground is where most of us fall, isn’t it? Depending on the situation, we all coulda been the main guy.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.