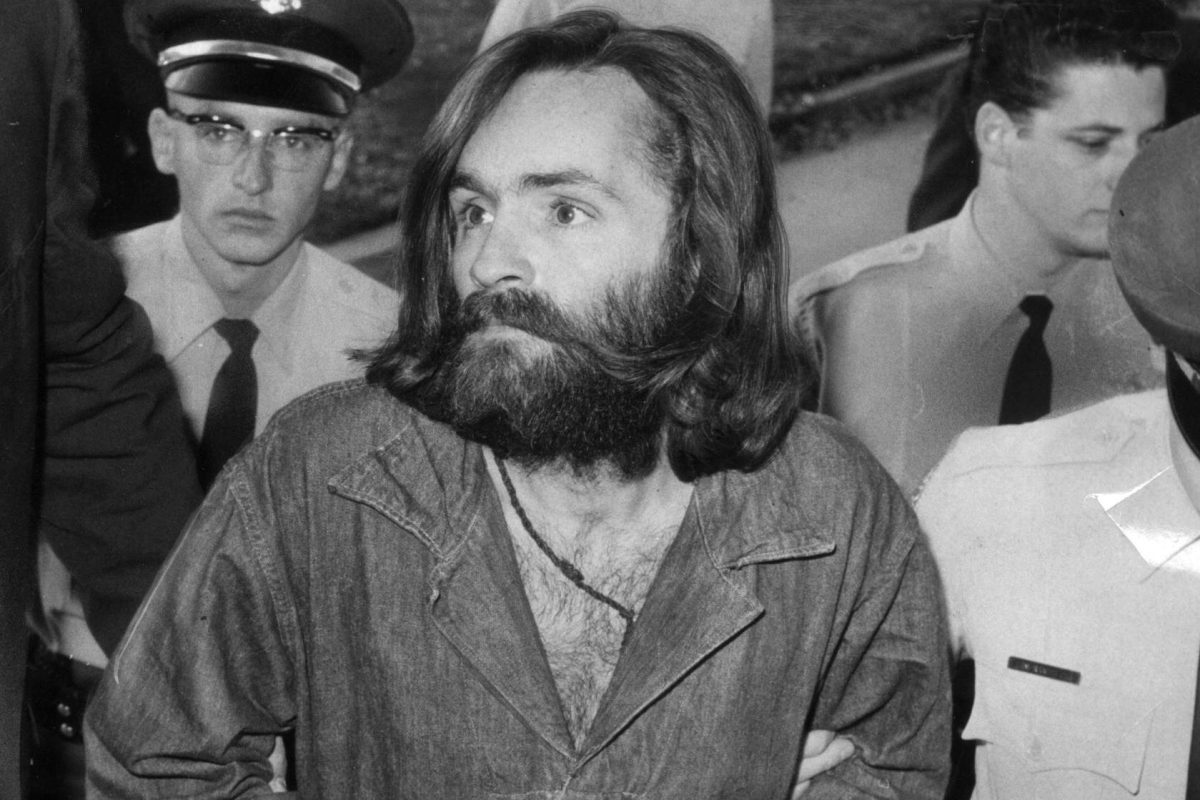

During the last year of his life at Corcoran State Prison in California, 82-year-old Charles Manson made a lot of phone calls.

The recipient of many of those calls, which were limited to 15 minutes by the state’s prison system, was documentary filmmaker James Buddy Day.

Day had initially contacted Manson because he’d heard the infamous cult leader believed he was innocent of masterminding the gruesome murders of pregnant actress Sharon Tate and six others in 1969, killings which began 50 years ago today at Tate’s home. Though Day was interested in doing a documentary about Manson’s claims about his innocence, he never dreamt he’d actually hear back from the convicted killer. But Day was wrong.

“I wrote him a bunch of letters and didn’t think in a billion years he’d call,” Day tells InsideHook. “Maybe I’d get a letter back or something. And then, out of the blue, he just called me this one time. The first time he called me, I thought he would never call again and that it would just be a story to tell at parties. Then he called again. And then he called again, and it became a reality that I could do this documentary and that he would contribute to it.”

Day spent the next year interviewing Manson by phone from his prison cell. He was the last journalist to have access to the man Rolling Stone called “the most dangerous man alive” in 1970. The tapes of those phone calls were the basis of the documentary Charles Manson: The Final Words as well as Day’s new book, Hippie Cult Leader: The Last Words of Charles Manson.

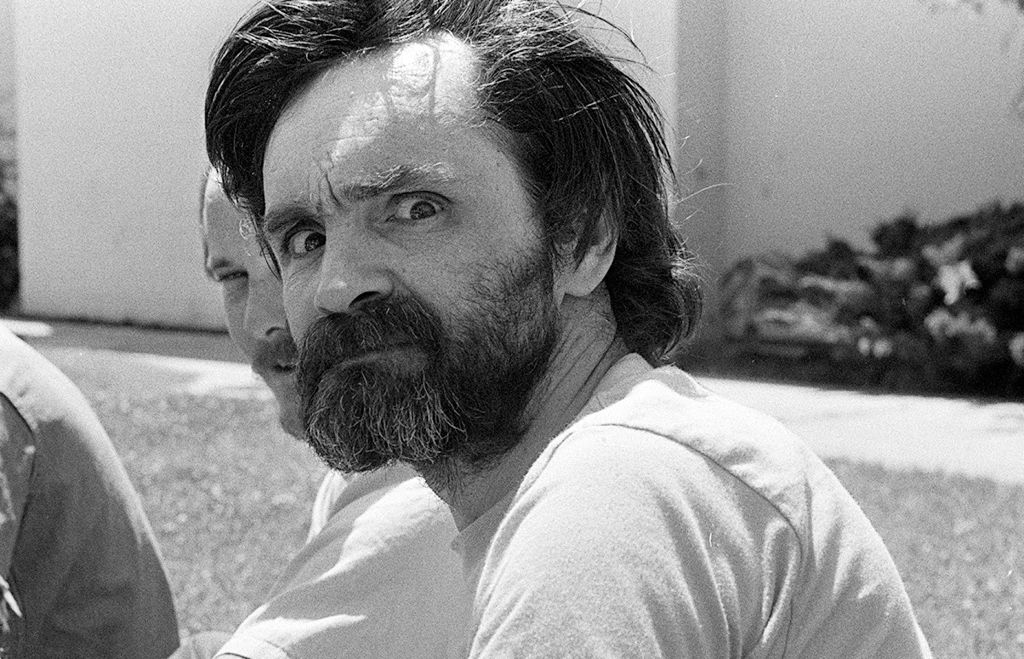

Day describes talking to Manson as “surreal” and says the aging icon “was aware of his own infamy” and knew his “name was terrifying to people.”

“I mean, the major thing about Manson, you have to know, is he would just reflect. Whatever you brought to him, he would just reflect that back to you.”

“He was this huge personality who was all over the place,” Day says. “I never knew what I was going to get when he would call. Sometimes he was a really good conversationalist. Sometimes he would just rant for 15 minutes. He talked in rhymes sometimes, kind of riddles almost. So, the whole thing was really just trying to decipher who this guy was and what he was saying. Manson was kind of stuck in the ’60s.”

Though the conversation mostly dwelled on the past, Manson was well aware of current events and public policy.

“As this kind of dark messiah, he attracted tons of people who would write him letters and set up these relationships with him. He would take any help he could get from anyone outside of prison,” Day says. “These disaffected white men would see him and embrace him to be subversive. He would manipulate them by getting them to sell things for him or taking money from them or putting them in touch with other inmates, all to better himself in prison.”

“He was aware of U.S. politics. I don’t recall ever speaking to him about Trump, but he definitely talked about Obama, who he wasn’t a fan of,” Day says. “Manson was raised in the Deep South in the Ohio River Basin … [And much later, in prison] he carved a swastika on his forehead. He kind of adopted a racist persona to align himself with people in prison who could protect themselves. He was definitely a bigot in that sense.”

It wasn’t just men the father-of-three would take advantage of, though.

“He had relationships with women who were looking for different things from him,” Day says. “The major thing about Manson, you have to know, is he would just reflect. Whatever you brought to him, he would reflect that back to you. That’s how he manipulated. That’s how he navigated the world. If you came to him looking for a father figure, he’d just give that back to you. A lot of women have brought something to him, and he would more than happily give it back to them for his own benefit.”

That type of behavior isn’t surprising considering the various philosophies Manson adopted.

“He had this kind of solipsistic philosophy where he was the only person that existed in the universe,” Day says. “He would talk about this kind of philosophy that he had where you are the only person that exists. ‘I am the only person that exists, that nothing else matters.’ It kind of made sense, because he was in prison for most of his life and so, to survive, he kind of adopted these ways of thinking that more focused on his inner self versus the outside world.”

Regardless of how he felt about the outside world, a spate of film over the last two years — including Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood — have made it clear that the world is still pretty focused on him, even though he died a week after turning 83 in November 2017.

In Day’s opinion, that’s not changing anytime soon.

“Manson’s story really does capture the 1960s in America. It’s become this kind of American folklore,” he says. “It has all these elements of sensationalism in it: a movie star gets killed, the dark messiah who manipulates teenagers and has a thrill kill cult, all wrapped up in the hedonism of the ’60s. When a story comes to represent a particular moment in time, it just seems to resonate forever. And I think we’ll be talking about Manson 25 years from now and 50 years from now, even 100 years from now. In the same way that we talk about Billy the Kid or Lizzie Borden or even O.J. Simpson.”

It makes sense, when you think about: that the same cult of personality that captivated young women in the 1960s would find similar footing in prison, whether it was from cellmates or desperate pen pals. And that even today, two years removed from his death, Manson’s story — however twisted and grim — continues to endure.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.