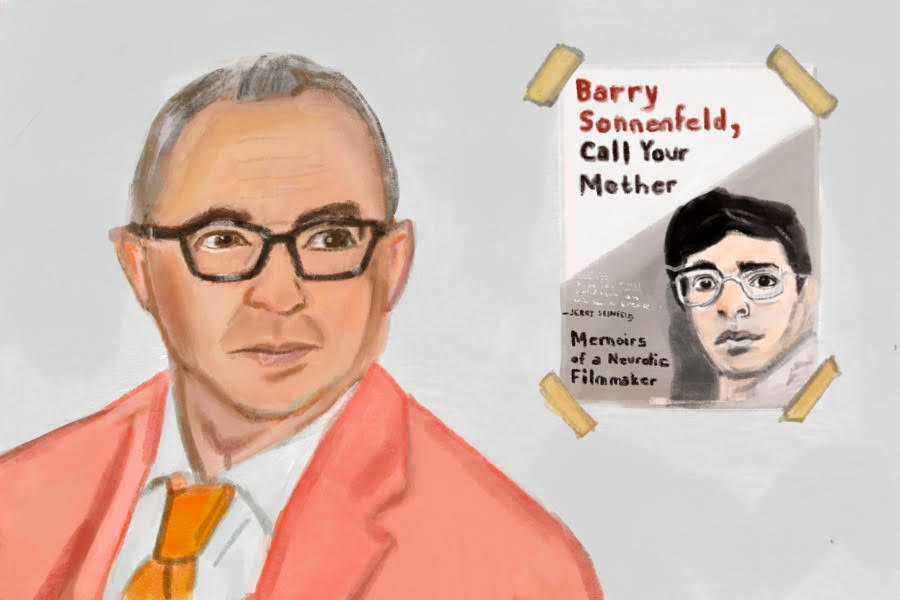

Welcome back to “The World According To …”, a series in which we solicit advice from people who are in a position to give it. Our newest installment features Barry Sonnenfeld, who made his name as the cinematographer on Blood Simple, Raising Arizona and When Harry Met Sally before directing a series of blockbusters that included Addams Family Values and Men in Black. His memoir, Barry Sonnenfeld, Call Your Mother, was just published. InsideHook recently caught up with the cinema legend to chat about memories, parenting and how to stick a pin in small talk for good.

InsideHook: Your book is so filled with wild, detailed stories — the rabbi on fire, your flopping around Bellevue naked, the repeated airplane malfunctions — that I was, for a time, suspicious. So I wanted to call a few people you write about to see if their memories track with yours. Most have their identity obscured, but Dolores French, a sex worker and memoirist who is the subject of a chapter, doesn’t. She says your rendering of history is true, except you didn’t drink vodka. She said you guys were perfectly sober.

Barry Sonnenfeld: Well, that’s the amazing thing about memories. We have three daughters, and we always remember trips differently. Sasha and Amy, our two oldest, will say, Remember when you and Barry were fighting in the car in Ireland? And I will go, No, we weren’t fighting in the car in Ireland at all. Everyone has their memories. So that’s adorable. I remember vodka, but maybe she’s right. It’s funny that you were able to find her because some of the other names I changed. I just felt, why drag them into it? I didn’t think Dolores would mind.

Did you keep a diary when you were growing up?

I recently found some diaries when I was cleaning out a box, but I never refer to any diary. I just have a really good memory.

I read a bunch of memoirs when I got hired to write this book. I do a little writing, changing scenes and stuff like that on movies or TV shows, but I’ve never sat down and written anything. And my problem with a lot of the memoirs I read, even the ones I loved, like Educated or The Glass Castle, was they were written in a way that I didn’t believe they really remembered it that way. When you’re three years old, and you say, “I looked out the window and the wind was blowing the wheat as if a sea, and the sun just barely rising above…” And I go, no, you don’t remember that. That’s just really good prose. And I tried to do some of that, and I hated it. I decided I was more of a storyteller than a literary genius.

Do you have a favorite curse word?

I guess it’s probably fuck, but it starts to lose its joyful impact if you overuse it.

So much of the book is about your parents, and the consequences of their poor decisions. Did you succeed despite your parents or to spite them?

It definitely wasn’t to spite them because if I really wanted to spite them, I wouldn’t have been successful. I think it’s ultimately really hard, if not impossible, to be a good parent. I had plans to be a good parent when Chloe was born. I knew what my mother and father did wrong and I wasn’t going to make those choices. And there I was, hovering over Chloe, worrying about her when she went for sleepovers. Being super concerned when she went to boarding school. Luckily, I have a fantastic wife who tempers my horribleness. I do think that all parents, in some ways, are not exactly good parents, and that anyone could write a book like mine.

You don’t put a gauzy sheen on events just because a person involved is beloved or dead or both. Penny Marshall, for example, comes off as indecisive and bumbling.

She was not bumbling. She was indecisive. Truthfully, what made that chapter a little bit easier to write was the fact that Penny is no longer with us. I think that if Penny was still alive, I probably would have lost some of the stuff because Penny was a good director and she did figure out really cool, funny ideas. It was her idea to have Hanks eat caviar because she knew a kid eating caviar for the first time would be disgusted. It was her idea to have those little baby corns so that Hanks could eat it as if it was a corn on the cob. She really knows where the jokes were, but her strength was not at all in visual storytelling. She didn’t understand my language.

We liked each other as people. She just didn’t like me as a cameraman.

When you wrote about people who are still alive, did you pull your punches?

Oh, God, yes.

What’s your worst habit?

My worst personal habit is anxiety and grinding my teeth, clenching my jaw, being a nervous wreck and, therefore, trying to tell everyone what to do. [Sonnenfeld’s wife] Sweetie and I will go shopping, then we’ll come home and I’ll say, If you put the butter in over there … And that’s when she says, You really need to get a job. Because left to my own devices, I’m like a border collie of humans. I’ll tell them where to stand, what to do, where to put the butter, why they should call instead of email, why they should email instead of text. That’s my worst habit.

Your book is the story of a nebbishy guy who skips from project to project, somewhat subject to forces beyond his control. But it’s hard for me to shake the feeling there was an alternate story happening, of a cutthroat Barry Sonnenfeld. Because when you reach your level of success, it happens because you make it happen. Was that a less appealing story, or is that really not you?

I do have very strong opinions, and I always tell people that the job of a director is simply having opinions about everything. It’s what a director does. When the prop guy says to you, Do you want the red envelope or the green envelope?, they never want to hear you say, I don’t care. They want to hear the green envelope. What I’m really good at in life is telling people the green envelope. And by the way: on the day of shooting, even though you pick the green folder, you forgot that you had told the wardrobe person to put the actress in the green dress. Now you can’t see the green folder because it’s camouflaged by the green dress. And you always admit you’re wrong. You never say, Hey, I told you the red folder. So I’m very nice and respectful of crews. But no, I’m not ruthless. I’m not nebbishy; I’m strong-willed and opinionated.

What words would you want on your tombstone?

“I knew it.”

Your cousin Mike, a serial child molester, appears pretty much throughout the book. To some degree, did his presence in your life make you the man you are today?

I hope not. I think in spite of Cousin Mike. He was a terrible, terrible creature who lived in our home for several years and molested — unnamed — many relatives, neighbors, all sorts of people surrounding us. And the fact that my parents knew about it … I knew they knew about it, but somehow I assumed they didn’t know the extent of it. As it turns out, they did. My father admitted it.

That’s why the ending of your book is so jarring. You still maintain that, despite being awful parents, they were good people. I find that hard to square with the Cousin Mike stories.

For the most part, people are neither good nor bad. My parents were truly beloved by hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people. As I make clear in that last chapter, where everyone stands up and talks about how my parents changed their lives for the better. My parents just were terrible parents and they were terrible to the kids that surrounded their child, and terrible to their nieces and nephews, and there’s no excuse for that. But they also were loved by literally hundreds if not thousands of people. They were good people. I actually really liked that chapter because it allows me to be mean to them, knowing I’m going to go there at the end.

If that were in a movie, wouldn’t you feel that was a cheap twist?

No, I would feel that it was real and I would appreciate it. I would like it because there is no black or white; everything’s got a little bit of gray in it.

What is a great if uncomfortable question to ask someone if you want a conversation to move past small talk?

“Were you happy or sad when your mother died?” I remember Joel and Ethan [Coen] called me one day and said, “Hey, Barry, just want to let you know our mom died yesterday.” And I said, “Oh, was that a good thing or a bad one? And they said, “Well, no, we actually loved our mother.” And I said, “Oh, okay, that’s allowed. In that case, I’m sorry.”

I think it’s a really good question because it takes people aback. So that’s my advice for an awkward getting-to-the-heart-of-the-matter-quickly question.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.