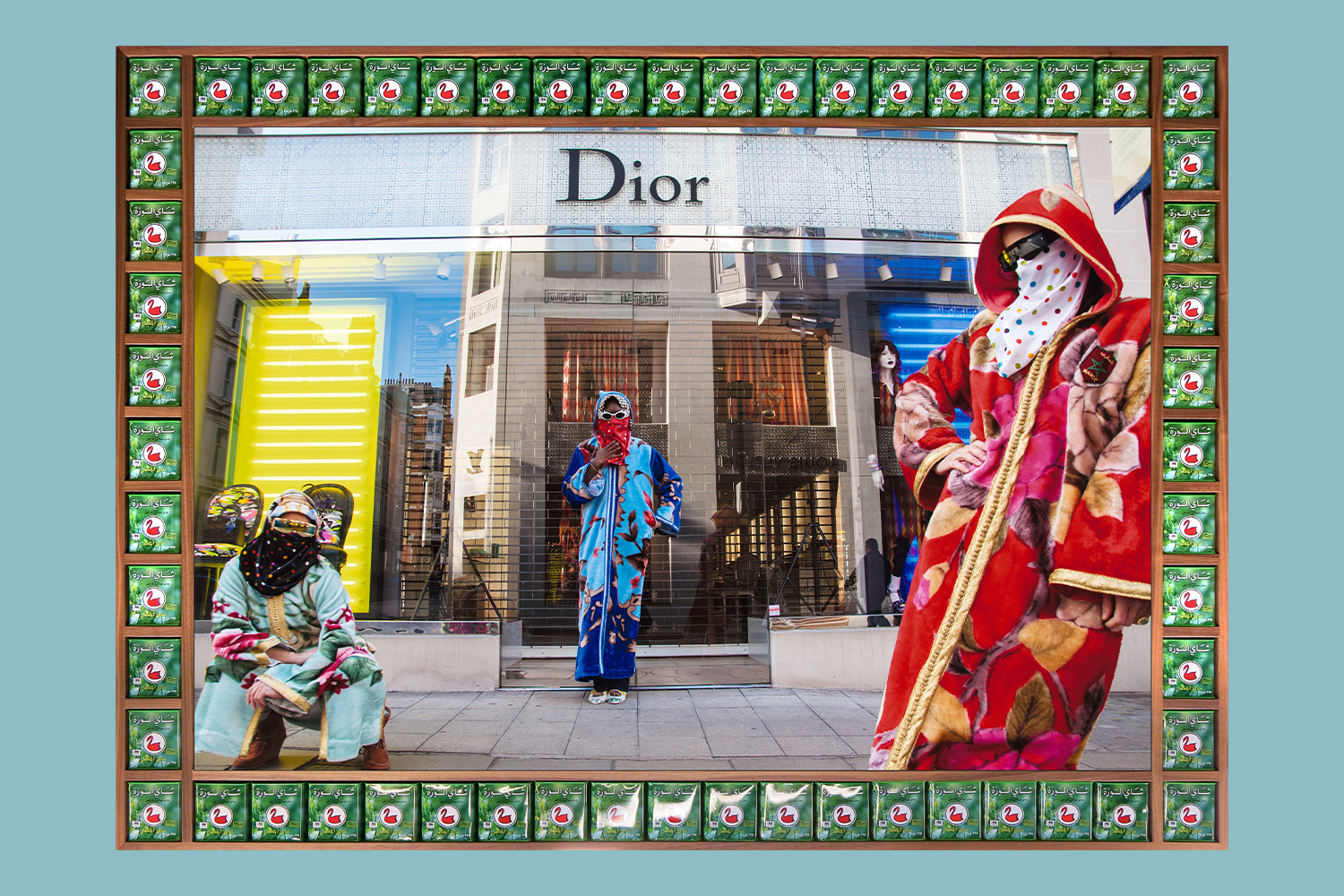

You know Hassan Hajjaj’s photographs as soon as you see them: bright colors, graphic compositions and wild patterns overlapping one another. The Moroccan photographer, who divides his time between London and Marrakech, recently opened a new exhibit at Fotografiska in New York City, called Vogue: The Arab Issue, which runs until November 7.

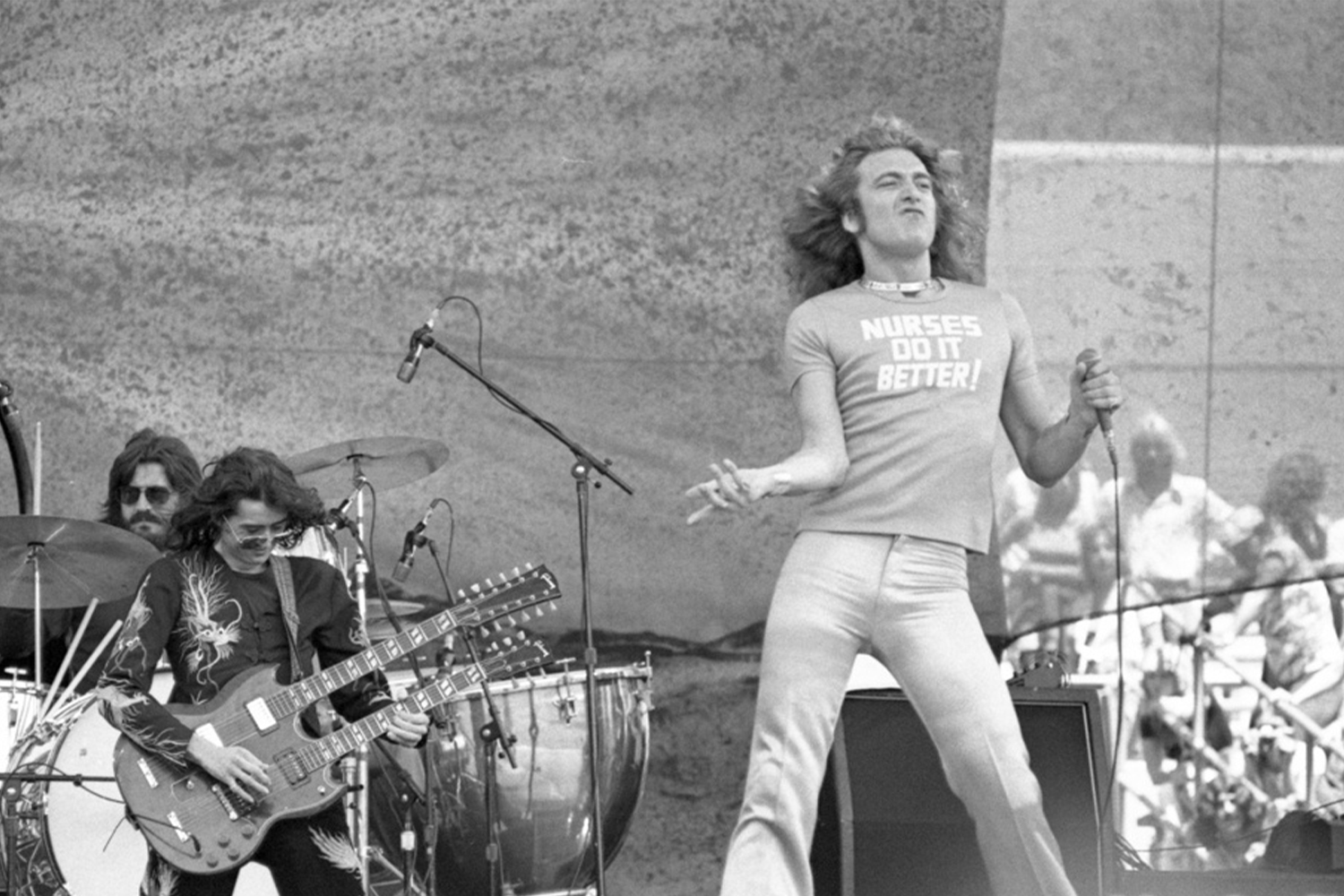

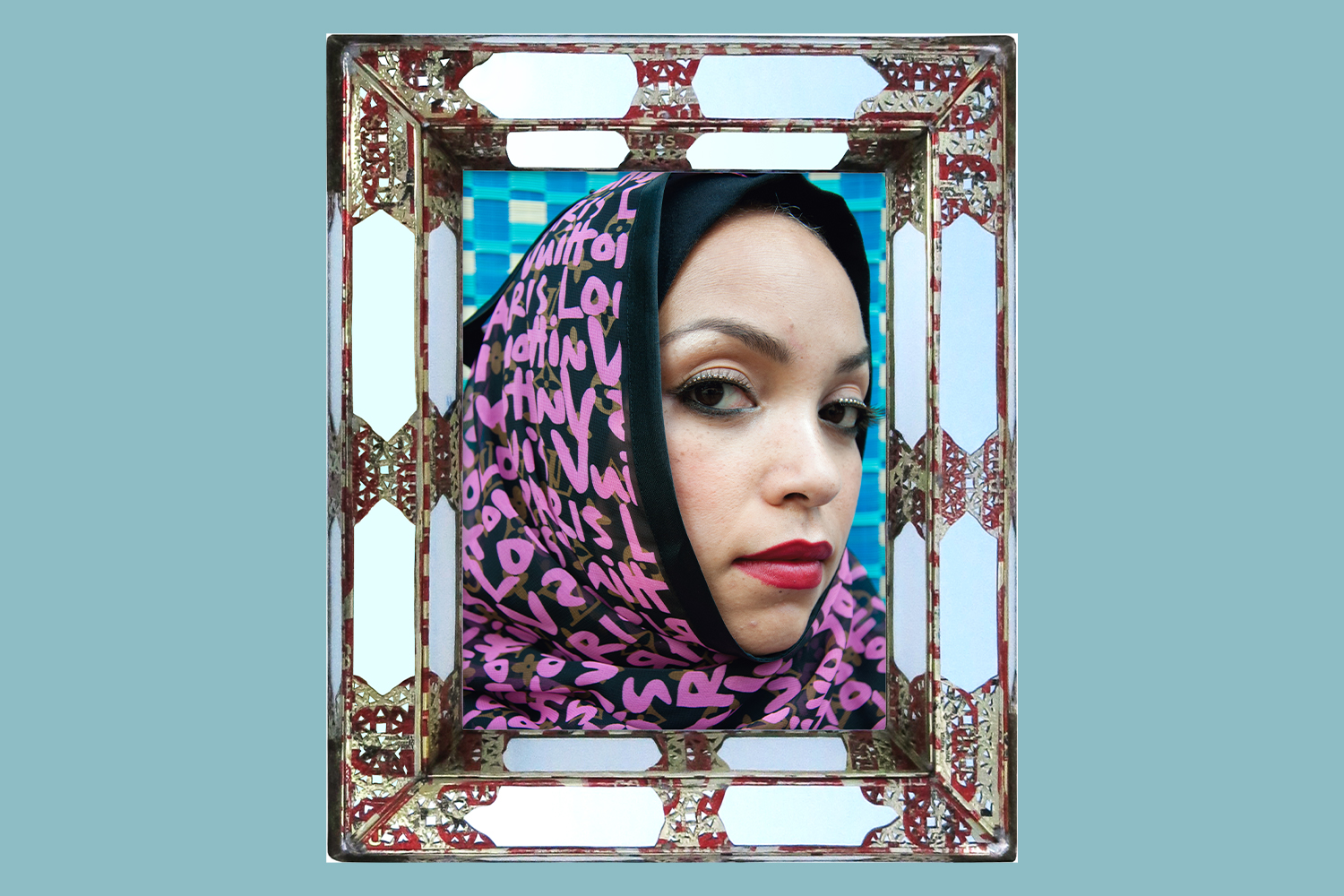

The retrospective features more than 20 years of his photos shot in Morocco and beyond, from his famed Kesh Angels series of a veiled girl bike gang to his fashion shoots on the streets of London. A concurring exhibition is also on view: Hajjaj recently opened a new gallery exhibition at the Yossi Milo Gallery in New York called My Rockstars that features portraits of his muses, mostly friends who are artists, designers and musicians. That one is on view until May 15.

There’s another kind of rock star that he shoots: the biggest and brightest celebrities on planet earth, be it Cardi B for W Magazine, Paris Hilton for Vanity Fair or Billie Eilish for Vogue, all in his signature style of Marrakech street photography.

More than just an artist, Hajjaj is an entrepreneur. He runs the Riad Yima, a fashion boutique, art gallery and tearoom inside a converted house in Marrakech, and recently released his own line of hip hop-inspired sunglasses with Poppy Lissiman. Next up, he’ll be launching a tea brand. He spoke to InsideHook from his home in Marrakech about his favorite neighborhoods, his muses and why shooting on the streets is an addiction that will never die.

InsideHook: Looking at the title of this exhibition, there wasn’t actually an Arab Issue for Vogue …

Hassan Hajjaj: No, it’s just a fancy creation for myself. It could have a double meaning: with the political stuff that happened a few years ago (the “Arab Issue”), and then you have the Spring/Summer issue of Vogue … so I thought, why not the Arab Issue? I’m just playing around with the wordplay and letting the viewer interpret as they want to. But we do have Vogue Arabia based in Dubai, as of last year, so times are changing.

In the blurb for the exhibition, it mentions that some photographers come to North Africa to use the exotic landscape as a backdrop for fashion shoots without digging into the culture. Is that correct?

I use Morocco because I’m here, but if someone wants a spring/summer shoot, they sometimes go to the Sahara or the Brazilian jungle for the summer look, so they’re using the backdrop to promote the clothes for the season. Morocco is one of those places. They’re not coming for the tradition or the culture that’s there, they’re just coming to shoot their collection.

You’re doing the opposite of that, right? Using local models and culture.

They’re not models, they’re just friends and people. There’s Henna girls, dancers, my neighbor, friends who work in a restaurant. Not model models, just people. It started because I wanted to show my people from Morocco while using textiles in a fun way — animal prints, polka dots and patterns were big when I started this series in the 1990s. I bought the fabric, made the costumes and dressed up my friends in Vogue poses, but with the backdrop of Marrakech. It’s Vogue-ish, but it has some tradition of the place, as well.

You started this style of photography — shooting women bike gangs or colorful patterned clothing and backgrounds — in the 1990s. When did it really take off?

It was like a step level that continued growing. It took about 10 years before I could show the whole story. When social media took off in the late 2000s, it totally took off. I started doing shoots internationally and social media helped push it, so people shared the work locally and globally. In Marrakech, the only way to really get around is by scooter. I wanted to highlight that with my Kesh Angels series of women bikers. It’s a play on Kesh, the slang word for Marrakech, and Angels, referring to Hell’s Angels. We used outfits, played around and made it cinematic. In the 1990s, in Europe, they thought it was strange to see veiled women on bikes. I played on that.

When you do personal, artistic shoots with friends and editorial shoots with celebrities like Cardi B, Billie Eilish and Paris Hilton, do you take the same approach?

They’re exactly the same to me. If I shot celebs differently, it would become more of a job. When I’m shooting for myself, it’s a different feeling. I don’t have any worry if its going to be a good image or not; I can decide after. There’s usually a triangle between me, the magazine and the celebrity — you have to develop a job where everyone is happy. But that moment, when I’m working with any celebrity, I treat them as if they’re any one of my friends.

Who are your muses?

I have a few. Karima, one model who has appeared in a lot of my work since the 1990s. Same with Jen, who is my assistant, who has been in lots of my work. I try to stick with the same few people.

How do you define the aesthetic of your work? Is the palette North African?

My work is for anyone who can see something in it. I let them decide what they see — if it’s cool, interesting, whatever. Growing up in Morocco, there’s so many bright, colorful people in our everyday culture. They’re not scared of color. Growing up in England (I left Morocco at 13 years old), the UK is cloudy and has less color. It highlighted my work to be more colorful, bolder, clashing colors to escape dreary London moments. Morocco has a big influence on my palette.

What do you wish people would understand about Marrakech?

I just think whenever you go to a place, it’s always good to not just come there, be selfish and take, but to understand the culture and the people. Not to compare it where you’re from, either. You’ll have a hard time once you start comparing. In Marrakech, there’s a lot going on. If you get to meet the real people, you’ll get to know the city beyond the sunshine, hotels and good food. I hope people would go out of their way and try to find something for themselves within the city.

What’s your favorite neighborhood in Marrakech?

I live in the heart of the Medina. There’s a small market there where the slaves were being sold. It’s got a history. I’m doing a project right now in Sidi Mimoun, the industrial area of Marrakech, which is great because it’s a different vibe but is halfway to becoming trendy. If you look at SoHo in New York or downtown Los Angeles or East London, they were all industrial areas before they became trendy. It’s nice to see a raw space that’s changing.

One photo in the exhibit is called “Dior” and is from 2012. Can you tell us about this one?

This photo was taken in the streets of London, but all my photos are taken in the streets. Even the ones with the backdrops, they’re not in a studio. I don’t work with lights; it’s on the streets. It’s part of a body of work of work called “Autumn/Winter and Spring/Summer Collection 2048.” The idea is that this is the part of the Arab Issue. My new gallery exhibit at Yossi Milo Gallery is called My Rockstars, another body of work I’ve been working on since the 1990s, was born in London. I realized I had incredibly rich people around me — musicians, artists, designers — who had something that inspired me. I wanted to highlight them and it has continued to grow as a big thing. I shoot that everywhere I go now.

Do you shoot in the streets because of the energy of the streets?

For me it’s addictive. I don’t know if it’s going to rain, who will pass by, the reaction of the cars driving by, loads of people jumping into the picture. I say: “Jump in if you want.” It creates a moment that makes you excited about the shoot and the sitter. I’ve shot in the streets of LA, New York, Paris, London, Dubai, Kuwait, countless cities. It’s normal to me.

What was your approach for this retro line of sunglasses that you designed?

It just dropped last month with Poppy Lissiman and we’re working on the spring/summer drop right now. It’s under the name Andy Wahloo, which means “I have nothing” in Arabic. They’re fun sunglasses, a bit of a rock star statement. The inspiration comes from the Gazelle eyewear, an Italian brand that was big in the 1970s, all the gangsters were wearing them. Then, the hip-hop artists picked them up in the 1980s. Since I grew up in that era, I took that inspiration and turned them into my own line.

Is Marrakech more progressive than it was 20 years ago?

Yes. But actually, it always has been. You have to remember; it was an imperial city that has been here for thousands of years. If you think of Rome, you feel its history. Romans have a certain character because they’re born into this city with this bloodline. Marrakech has that as well — some of the buildings here are 800 years old. It’s embedded into Marrakech people. It takes over.

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.