On Wednesday, November 15, 2017 Ryan Riggs confessed his worst sin to the pastor and congregation at North Lake Community Church in May, Texas. Most 21-year-olds might bare their souls in a sanctuary with stories of petty crime, or substance abuse, or sex out of wedlock.

Riggs confessed to the unsolved May, 2016 rape and murder of Chantay Blankenship, age 25.

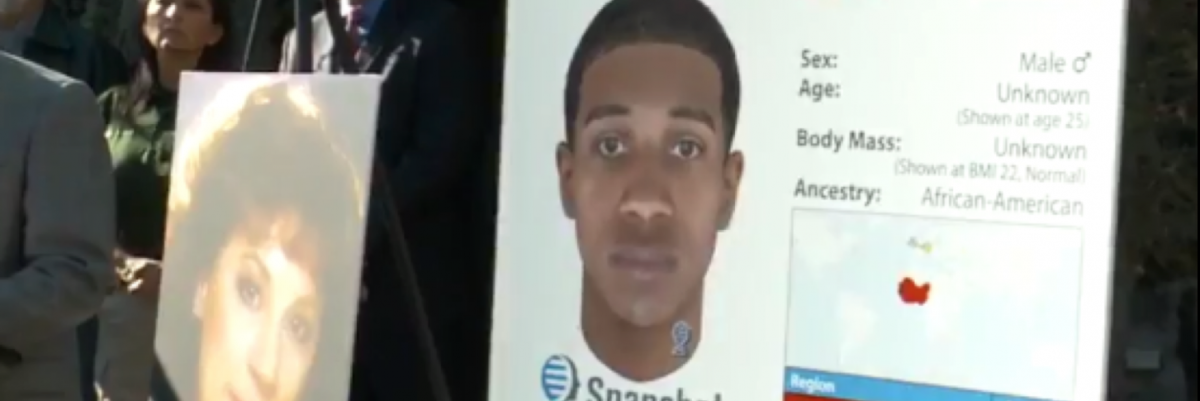

By then Riggs’s face had already been in the news, but not his name. In fact, Brown County Sheriff Vance Hill later told local media that Riggs had never been “on our radar at all.” The young man’s image had been conjured from unknown DNA found at the scene of Blankenship’s murder. With that genetic material, Parabon Nanolabs in Reston, Virginia had developed a portrait of a male with Northern European ancestry, “fair” to “very fair” skin, blue or green eyes, brown or blond hair, and few to no freckles.

Parabon profile; Riggs mugshot.Parabon’s Snapshot Phenotyping had determined the man’s ancestry and created a portrait using his likely features. The result was uncanny—so uncanny that on seeing it, Riggs went on the run before confessing, admitting he’d raped Blankenship then beat her with a lawnmower blade.

Parabon NanoLabs isn’t the only company offering DNA profiling services to law enforcement, but they are perhaps the most well-known. They have an impressive record, given just how new the technology is. Police all across the U.S. have used the Snapshot service in their efforts to put a face on unknown killers—and sometimes on the bones of the unknown dead.

Just a few examples include a Snapshot portrait of a possible serial killer who attacked Aurora, CO residents in 1984, ultimately brutally murdering three members (PDF) of the Bennett family, Parabon even aged the image to what the killer might look like today. More recently, Parabon developed an image from DNA left by the unknown assailant in Utah who stabbed South Salt Lake bookseller Sherry Black in 2010.

And in a case every bit as impressive as the one that culminated in Ryan Riggs’s surrender, a profile developed from evidence in the 1992 murder in Agawam, MA of Lisa Ziegert proved to be a striking likeness of the man arrested for the crime, Gary Schara.

Successes notwithstanding, it’s hard to ignore some potentially huge problems with these portraits.

Press coverage of cases ending in arrests has tended to treat Parabon Snapshots as nothing short of miraculous, but scientists and legal experts see serious issues. Columbia professor Yaniv Erlich studies genetics and in October, 2017 he told the New York Times that the complexity of the way genes establish appearance makes predicting what someone looks like “on the verge of science fiction.”

Determining ancestry, Erlich said, is “fairly simple. Kinship, too. Phenotyping with faces? Forget about it.”

In an article about the arrest of Ryan Riggs, the Associated Press (AP) quoted ACLU senior policy analyst Jay Stanley on the perils of making these sketches public at all:

“You can lose weight, gain weight, change gender, grow a beard, have plastic surgery,” Stanley said. “It risks ensnaring innocent people in webs of suspicious investigations. It risks playing on existing societal racial prejudices. It risks diverting investigations down wild goose chases. If this technology were used to set up dragnets say to bring in every albino person in an area as a suspect because the DNA seemed to show someone had that trait, that’s where we would object.”

Parabon CEO Steve Armentrout told the AP that phenotyping “isn’t meant to provide a positive identification. It’s meant to jog someone’s memory.”

Parabon’s Snapshot webpage states that their “DNA Phenotyping System accurately predicts genetic ancestry, eye color, hair color, skin color, freckling, and face shape in individuals from any ethnic background, even individuals with mixed ancestry.”

They note that there are traits which can be heavily influenced by “environmental factors,” not just DNA, and those “trait predictions are presented with a corresponding measure of confidence, which reflects the degree to which such factors influence each particular trait.”

Other traits are much more heritable, according to Parabon, like the color of your eyes. Those, it states, “are predicted with higher accuracy and confidence than those that have lower heritability; these differences are shown in the confidence metrics that accompany each Snapshot trait prediction.”

Consumer DNA analysis from companies like Ancestry.com and 23andMe determine geographic ancestry with relative ease and at a much lower cost than the $4-5,000 fee Parabon reportedly charges law enforcement for its services.

23andMe estimates several likely physical traits—not unlike Parabon profiles. As Parabon’s techniques are secretive and proprietary, the companies may follow radically different procedures, for all we know.

Still, it’s worth noting a simple example of just how mixed the results of any phenotyping can be.

In my 23andMe DNA profile, the company’s analysis resulted in 19 reports about my “physical appearance, preferences, and physical responses.” The company based them, it stated, on “current knowledge of how genetic factors influence our traits.”

Many of the estimates were on the nose. One report stated I was likely to have blue or green eyes—I have green eyes, so this was close enough. Another said I might prefer salty food. Also true.

But when it came to a few key physical traits, 23andMe’s estimates—at least—were way off.

According to them, I am unlikely to be freckled, red-haired, or have a cleft chin. I am likely to have fair skin, light brown hair, and a square chin.

I am a freckled redhead with a cleft chin.

This may be apples and oranges. Perhaps Parabon’s Snapshot technology is far more sophisticated and granular than whatever 23andMe uses to generate its reports—we could be comparing an Xacto knife to a butter knife.

Still, the first time I read about a Parabon Snapshot profile, I considered my 23andMe results. It occurred to me: If Parabon used even remotely similar methods to 23andMe in creating a profile based on my DNA, it might render a portrait of a man who doesn’t look anything like me.

This is just based on one man’s casual comparison, not some rigorous study, so take it with a grain of salt.

But it is just enough to perhaps make anyone blown away by the admittedly striking successes of some Snapshot profiles take a step back from considering this technology some kind of magic bullet.

The law enforcement community is by its nature skeptical. Courts also require plenty of evidence beyond DNA. It’s the media who perhaps need to treat stories involving eerie digital images—that may or may not show the face of a killer—with a little less wonder and a lot more skepticism, for their viewers’ and readers’ sake.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.