“What lit the fuse was humans traveling more.” So says Nicholas J. Schroeck, director of the Transnational Environmental Law Clinic at Wayne State University Law School, in reference to the nationwide explosion in invasive species populations. (Full disclosure: The author of this piece is friends with the professor.) Schroeck, who is also an assistant clinical professor, has studied the ill effects of invasive species for a decade, with expertise in the area of the Asian carp. (The fish, unlike some invasive species, were brought over to the U.S. intentionally to help clean up catfish farming lagoons and treat sewage. But when they escaped their environs all ecological hell broke loose.)

If you’re unfamiliar with the problem of invasive species, it’s been a pervasive one for centuries. What happens is everything from foreign cargo ships to Uncle Bob’s fishing boat find their way into different ports, unknowingly carrying weeds or the eggs of an invasive species, and boom! A new creature gets introduced into the environment and has an adverse effect on its native or endangered/protected species. In the Great Lakes region alone, says Schroeck, there are over 180 invasive species that have been shuttled in via international shipping and have now set up shop for good.

What can the average Joe do to prevent this sort of thing from happening? Well, beyond making sure your boat is properly cleaned before putting down anchor in a new area—and supporting all the invasive species–hunting contests out there—it’s pretty simple: be responsible. Says Schroeck:

“If you are really into [your] aquarium, [buy fish] from reputable dealers that aren’t selling you fish that shouldn’t have been caught or bred in the first place. And then [don’t release] them into the wild. It could potentially lead to all types of problems.”

That exact issue recently reared its ugly head, when a monster goldfish turned up in Australia. (Click here for more on the “feral goldfish invasion.”) “The ‘goldfish problem’ is similar to the threat from Asia carp,” says Schroeck. “With goldfish, the problem is humans. Specifically, people who release goldfish into surface waters where they can often thrive, eat a lot, and reproduce.”

The invasive species problem isn’t just costly to local ecosystems; it hits us all in our wallets as well. Schroeck notes that it’s been estimated that the Asian carp problem could cost $7 billion for the sport and commercial fishing industries in the Great Lakes region alone.

Below, take a look at some of the worst invasive species, along with notes about each of them from Schroeck.

Asian Carp (China)

Origin: China

How They Arrived: Imported to the U.S. to help clean ponds, as well as for sewage treatment purposes

“A very significant threat to the Great Lakes ecosystem and Great Lakes fisheries. They are voracious eaters and reproduce faster than rabbits. The concern is that they will completely destroy the food chain.”

‘Goldfish’

Origin: China

How They Arrived: Introduced as pets in 1850s

“The lesson here is that people should not release pets from their aquarium into the natural environment.”

Snakehead Fish

Origin: Africa/Asia

How They Arrived: Introduced intentionally as a source of food

“They look creepy with their shiny teeth. Without native predators, they can jump in line to the top of the food chain in an ecosystem and cause problems for many species. They can survive on land for three or four days as long as they are wet. And they can ‘walk’ on land by wiggling their bodies and pushing along with their fins.”

Zebra Mussels

Origin: Eastern Europe

How They Arrived: Oceangoing ships via the St. Lawrence Seaway

“The Zebra Mussel, which was introduced to the Great Lakes through oceangoing ships, has upended the Great Lakes ecosystem. They are filter feeders, and they have eaten up many of the small organisms that other native species depend upon.”

Asian Stink Bug

Origin: Asia

How They Arrived: Accidentally, via shipping crates

“These are a big threat to agriculture. They feed on apples, peaches, [and] corn, damaging the produce. Their ‘stink’ can cause allergic reactions in some people.”

Emerald Ash Borer

Origin: Asia

How They Arrived: Cargo ships or airplanes

“This little critter, native to Asia, kills ash trees with [only] a few years of infestation. The larvae eat the underside of the tree back, sapping the trees of nutrients and eventually killing them.”

Round Goby

Origin: Eurasia (Black Sea/Caspian Sea)

How They Arrived: Cargo ships

“[N]ative to the Black and Caspian seas. They can out-compete native fish and survive in areas of poor water quality. They have been found to eat Zebra Mussels, another invasive species, but they don’t eat enough of the mussels to eliminate them. They are also known to steal bait off of fishing hooks!”

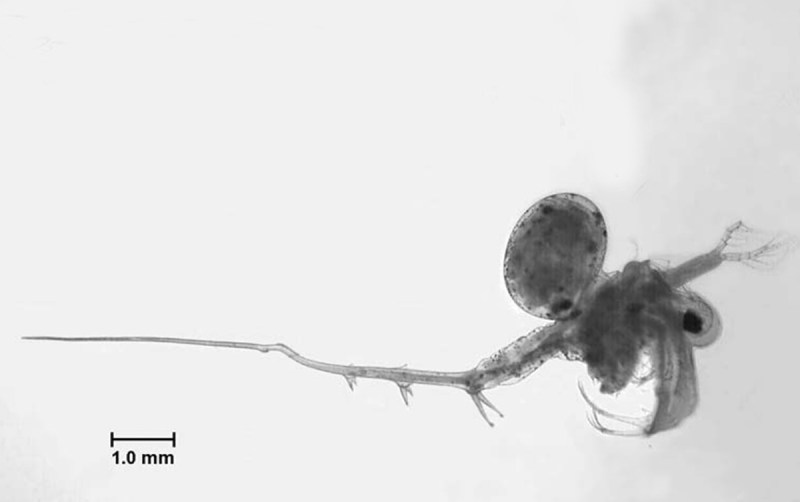

Spiny Water Flea

Origin: Eurasia

How They Arrived: International cargo ships

“They are native to Europe and Asia, [and] eat zooplankton and Daphnia, small organisms that are [at] the base of the Great Lakes food web. They also cause a nuisance on fishing lines by clogging the eyelets on fishing poles.”

Nutria

Origin: South America

How They Arrived: Intentionally imported for their fur in 1930s

“They are large ‘river rats’ that destroy marshlands across the southern United States. They were introduced in order to farm them for their fur, but they eventually escaped and have been causing serious problems in wetland areas ever since.”

Pythons

Origin: Africa/Asia/Australia

Anacondas

Origin: South America

How They Arrived: Introduced as household pets; escaped or intentionally let into the wild

“Anacondas have become a problem in Florida, along with pythons, which have received more attention. Anacondas are illegal to own in Florida for personal use, because if they escape or are released, they can decimate the ecosystem by eating native wildlife. Native to South America, they can grow to around 20 feet in length, and can move very quickly in the water.”

Will Levith, RealClearLife

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.