Did Lou Reed change the world? Yes — and in more ways than one. Reed’s musical influence, including but not limited to his work in the Velvet Underground, shaped generations of rock musicians that followed in his wake. There’s also the matter of his influence on future Czech Republic leader Vaclav Havel, his sexuality and his forays into art, all of which make him one of the most singular artistic figures of his time. And now, Will Hermes has written a comprehensive Lou Reed biography that does justice to the disparate works and occasionally contradictory life of a musical icon. Lou Reed: The King of New York is as wide-ranging a book as you’d expect from the author of the immersive musical history Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, and it’s a biography that’s attuned to the nuances of Reed’s musical collaborations across the decades.

There’s a fascinating element to the arc of Hermes’s book as well, which involves the contrast between Reed’s occasionally stratospheric ambitions and his penchant for undermining himself. InsideHook spoke with Hermes about the challenges of writing about Reed, the role mentors played in Reed’s career and an unexpected foray to a Dallas Cowboys game.

InsideHook: After finishing Lou Reed: The King of New York, I was thinking about connections between it and Love Goes to Buildings on Fire. Your previous book covered a lot of different genres and styles happening in New York in the 1970s, and I thought it was interesting that Lou Reed ended up working with a lot of musicians with ties to those genres — Reuben Blades and Don Cherry, among others. Did you see that as a connection between the two books? Do you see other connections between the two books?

Will Hermes: That’s a great observation, which I hadn’t really perceived going into the book. The connection that I saw between the two was really a wide angle lens on the art scene of the city — specifically the music scenes. But Lou Reed, even more than the first book, explored the art scene writ large. He was involved with literary things. He was obviously involved in the experimental film world in the early days and in the less experimental film world in later days. And the connection, in terms of all those different genres of music, revealed itself along the way.

This is the first time I’m hearing it mentioned in terms of totalizing it in hindsight. Lou Reed listened widely, even though sometimes his music can get pigeonholed. He was a fan. He was a fan of everything, listened to everything and collaborated really broadly.

One of the aspects of this book that I found very moving was when you wrote about the music he was listening to at the very end of his life, and the fact that a lot of it was very current. He wasn’t someone whose tastes calcified as he got older, which I found very revealing — in a good way — about him.

Coming across the playlist of music he was listening to in his final days and hours was really moving. He did a great radio show for some years with the late Hal Wilner on Sirius. There are still a few episodes you can find floating around the internet, and I highly recommend folks to go check them out if they’re still there because they’re great. Wilner, of course, was an omnivorous music maven. I think he brought a lot of stuff into Reed’s orbit.

That was another interesting thing that came full circle. You wrote about his days as a college radio DJ, which was long before the phrase “college radio DJ” was very indicative of a particular approach to music. That he would return to that decades later was a nice bit of synchronicity.

Yeah. It moved me a lot because I have to say, my whole music career really started by doing college radio. I did my first deep dive into the Velvet Underground via college radio. So that’s fitting.

Was that your first exposure to Lou Reed, or was your first exposure to him more through his solo work post-Velvet Underground?

It was his solo work. I discovered him in Queens listening to WNEW-FM and WLIR-FM. “Walk on the Wild Side” was all over the radio when I was 11 or 12. I remember really, really taking note of it when Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal entered my world in high school. That was the heavy metal version of Lou Reed. I sort of dialed it back to discover the Velvet Underground in college.

In the biography, you wrote very eloquently about Reed’s music across his career. I was interested in the fact that you didn’t go too far into, say, ranking some of his records as better or worse than other ones. Did you make a conscious choice from the outset to discuss the music more in the context of his biography?

I guess so. It’s funny. I didn’t intentionally try to avoid doing that, but I guess part of the joy of writing a biography is that you can get away from the quantification. Certainly, during my years as a critic, part of the job is quantifying and rating and comparing and creating hierarchies. In the context of this book, I wanted to paint a broader picture of a human being making art. Those things get alluded to; I think you can probably gather from reading the book that my love of the Velvet Underground kind of towers over everything.

But one of the things that really struck me about doing a deep dive into even records of Reed’s that I’d dismissed as not great is how even on his mediocre albums, there’s almost always an example of his mastery as a songwriter and a writer, even in those later albums.

How much did you know about Lou Reed’s life going into this project? And were there things you learned when researching it that surprised you?

I knew a lot. I thought I knew a lot about his life. I certainly had followed his work, and ever since I encountered him, I read a huge amount on the Velvet Underground and about Reed in magazines and a bunch of books. There were a lot of people who’ve written about him over the years, and there were a lot of surprising things. The fact that he had a fist fight with Bowie, him playing the White House — maybe these things vaguely registered in my consciousness, but during the course of my research, that was striking.

Also in his later life, he had such a reputation as a dick, just as kind of like a mean, grumpy guy. But hearing how kind and sweet and generous he could be and how beloved he was by people in his life, that was pretty striking considering the public persona of him could very often be, “Oh yeah, the nasty guy who shuts down journalists.”

I loved the story you tell in the book where he was critical of the cost of a belt, and the clerk responded by saying, “Well, the person who made this is very good at their job.” Seeing that that could get Reed to open up seemed pretty revealing.

That was one thing I learned from the New York Public Library archives at the Performing Arts library at Lincoln Center — that that dude was a connoisseur of everything. The best of everything, whether it was clothes, whether it was alcohol, whether it was camera equipment, whether it was guitar gear, certainly, and stereo equipment and clothing and you name it. He was a polymath. Even regarding the Asian diaspora restaurants of Flushing, Reed and Hal Wilner, apparently, always stayed current on the new hot places in Queens to get soup dumplings or what have you.

You mentioned the fight with David Bowie earlier, and you write about some of the very fraught professional relationships he had — with John Cale, Robert Quine and Doug Yule. It was interesting to me that, in all of these cases, Reed had substantial fallings-out with them, and yet they all ended up working with him again. What do you think it was about him that caused so many people to resume those musical relationships even after they’d had fallings-out?

He definitely was quite charming and compelling. And I also think people understood that he was a great artist — and more than that, that he was a great collaborative artist. When he let people in to work with him, I think he made his strongest work, which is why I devoted a lot of the book to talking about sidemen and women of his who were great in his orbit and made his work greater.

I mean, certainly Maureen Tucker, certainly somebody like Robert Quine and [John] Cale as well. The music they made together was great, but he was a difficult guy to work with. But he also did forge a lot of relationships that he sustained for quite a while.

Did his hostility to a lot of press and journalism cause any stumbling blocks as far as your research for the book?

Probably. I mean, nobody said it exactly that way, but I think the fact that he was very skeptical and suspicious of journalists — guilty until proven innocent, maybe. But he also had really great relationships with certain writers. If he trusted someone and opened up, which he did occasionally, he gave some really illuminating interviews over the years.

I think people were protective because a lot of people wrote a lot of shit about the guy over the years. There’ve been hatchet jobs. Journalists don’t like subjects that are nasty to them. So there’s been some nasty stuff written — some of it fair, some of it not. I think people were protective.

So yeah, it took a while. There were some people who didn’t speak to me initially, and it took a while to bring them around. They had to sort of vet me, but that was one of the really interesting things about taking the time to write a book like this.

How long from beginning to end did the process take?

There were hiccups along the way, but I started the project not long after he passed, and it’ll be 10 years since his death next month. So it was spread out over the course of that time.

How a Long-Lost Lou Reed and John Cale Documentary Was Finally Resurrected

Recorded in Brooklyn in 1989, “Songs for Drella” was the pair’s first performance together since The Velvet Underground disbanded 17 years earlierI knew about the connection between Reed and writer Delmore Schwartz, but I don’t think I realized the extent to which Reed had always had a foot in the literary world until I read your book. It feels like a huge loss that there are not several volumes of acclaimed books with his name on the spine, like Leonard Cohen.

Yeah. Certainly he was friendly with Leonard Cohen, knew him back in the day and really admired his work. The stuff that exists of Reed’s writing — the essay Fallen Knight and Fallen Ladies is amazing. The estate has been releasing some of his poetry and short prose work.

I did research up at Syracuse. He did a literary zine when he was at Syracuse, kind of a Samizdat-style literary zine. It ran for three issues, and there was some of his early writing and poetry in there. That’s pretty interesting too.

He talked about writing a memoir that didn’t happen. Although a book on Tai Chi that he’d started was published recently, and that’s worth checking out. It’s kind of an oral history of his interest in the martial arts form. It’s broader-spectrum than that, but it’s a great volume.

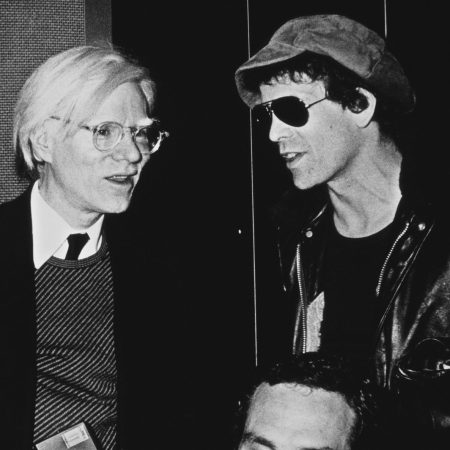

One of the recurring themes in Lou Reed is Reed’s search for mentors — including both Delmore Schwartz and Andy Warhol. Did you see anybody else in his life who kind of fit that bill? Or was there a point where after his relationship with Warhol had become fractured, he had moved past the need to have to have a mentor at that point in his life?

You know, I don’t think so. I think it’s a mark of his continuing vitality as an artist that he understood that he benefited from mentors. I know when you meet somebody who’s smarter than you or smarter in a different way, if you’re smart, you want to learn from them. You want to collaborate if you can. In meeting Doc Pomus, he learned a lot from Doc in his final years about songwriting.

His collaboration with Robert Wilson, I think, was a mentor relationship as much as it was a relationship between equals, on that trilogy of musical theater pieces, which are little known. It was fascinating to explore that work. And also Hal Wilner, I think, was a mentor and a best friend right up until the very end. And I think he learned a lot from Hal and kept current on new music and such. Laurie Anderson, I couldn’t call her a mentor, but I think that she was a huge revitalizing force creatively in his life as well, even though they were partners and married.

As you wrote about, there were times where Reed could be contentious, if not outright abusive, on both a personal and professional level. But especially as he grew older, he seems to have had this very generous side. Was his martial arts practice a way to sort of address some of those issues within his life?

I think certainly the discipline involved in studying Tai Chi — Kung Fu initially, and then Tai Chi — was part of him wanting to master his mood, master his temper. That was certainly part of it. His spiritual practice as such was folded into that.

He was a complicated person. I never really set out to become a biographer, but there was something about Reed’s story after writing my first book that I saw as a sort of microcosm of the entire post-war New York art world reflected in him. I was inspired to spend a lot of time with one subject and I really tried to lay it out. There were some not-so-nice aspects of him and there were some really admirable aspects of him.

I think everybody’s got dark and light within them, and his played out on the stage a lot of the time. I think he worked on himself for sure, as most good people do, to try to try to be better and correct his faults. So that was kind of inspiring.

As a lifelong Northeasterner, I found it interesting that — with very few exceptions — Lou Reed lived almost entirely in the New York metropolitan area. Did you ever get a sense that he ever considered being out of New York for any prolonged period of time, or was he always drawn to being around the city for personal and creative reasons?

It’s an interesting question because in his later years, he definitely did much of his touring in Europe. And I think there was an appreciation for him as an artist across the entire breadth of his career in Europe in a way that maybe he wasn’t appreciated here. There were periods where he would do a bunch of shows in Europe and hardly play in the States at all; maybe a handful of dates in the Northeast.

But I got no indication that he ever wanted to move out of the New York area or made any moves to — even after 9/11 when he was in the city living downtown when it happened. Even after that, he and Laurie doubled down and stayed living downtown, not far from the site of the World Trade Center. So yeah, New York was to him what Dublin was to Joyce for sure.

There’s a moment where you describe the Velvet Underground going to a Dallas Cowboys/Philadelphia Eagles game while they were on tour, which made my head spin a little bit. I like sports and esoteric music myself, but the mental image is still a little dissonant. Where did you find that particular piece of information?

Reed actually talks about it on a famous bootleg recording from a show in Dallas — I think End of Coal Ave. is the name of the club. I tried to do as much research as I could to expand the story. But yeah, that’s one of the interesting things you know about an artist, especially a musician, from their persona.

Certainly Lou Reed, as he would say many times in interviews, was a construction. It was a persona that sometimes was 90% him and sometimes it was 20% him, but — and I’m paraphrasing here — it was never 100% him. He was interested in sports. He was interested in boxing; he was a boxing fan like Dylan. Things that you might not expect the “Lou Reed” character to dig, he dug.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.