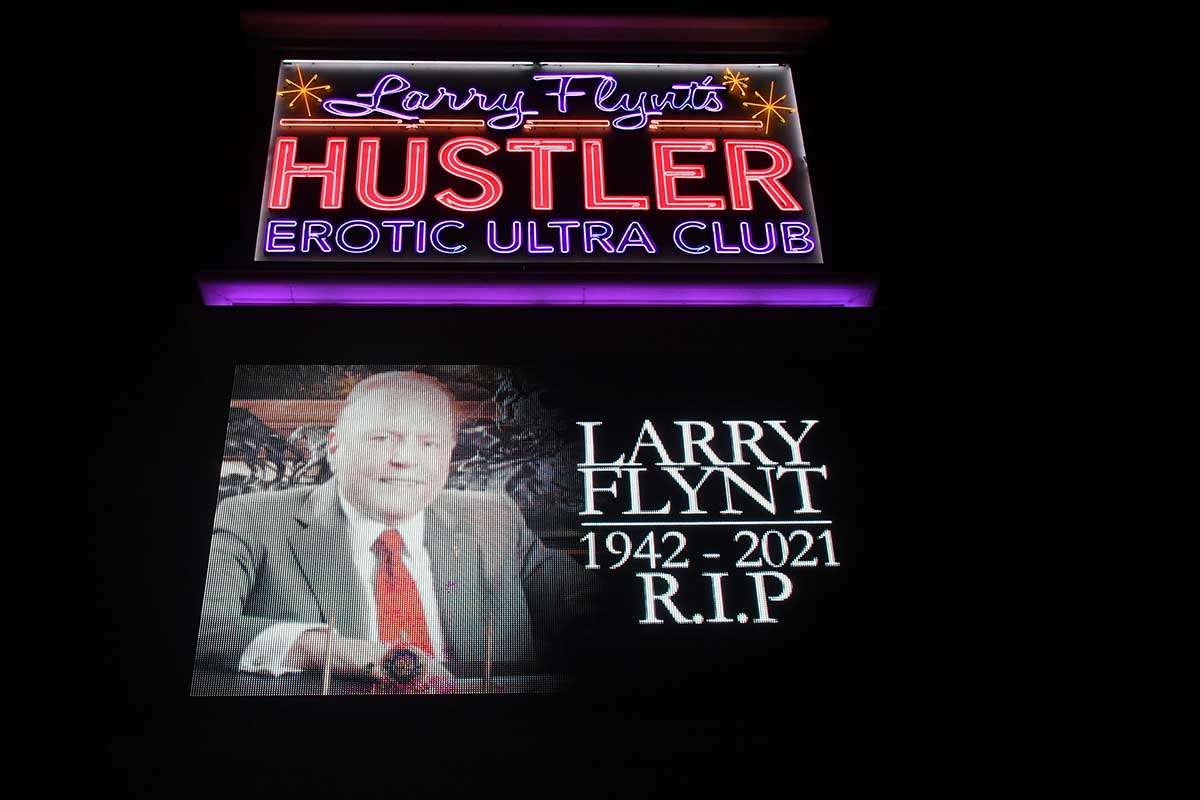

Even in death, our thoughts on Larry Flynt are contentious.

The Hustler publisher died on Wednesday at his home at the age of 78 of heart failure. Flynt had been confined to a wheelchair since 1978 after a sniper shot him and he was partially paralyzed; this happened during a week when he was facing a Georgia court on an obscenity trial. According to the New York Times, the shooter was a white supremacist who objected to the interracial couples he saw in the pages of Flynt’s pornographic magazines, and he never faced trial for that incident, although he was later jailed and executed on unrelated murder charges.

And that pretty well sums up Flynt: pornography, obscenity, outrage, free speech. The Times called him an “unpopular hero” for vehemently protecting (and pushing to the extremes) the First Amendment. Jezebel’s obit tagged him as “an American myth” and also a “creep.” And Politico got it pretty much right with the headline, “Larry Flynt, porn purveyor and unlikely free speech champion, dies.”

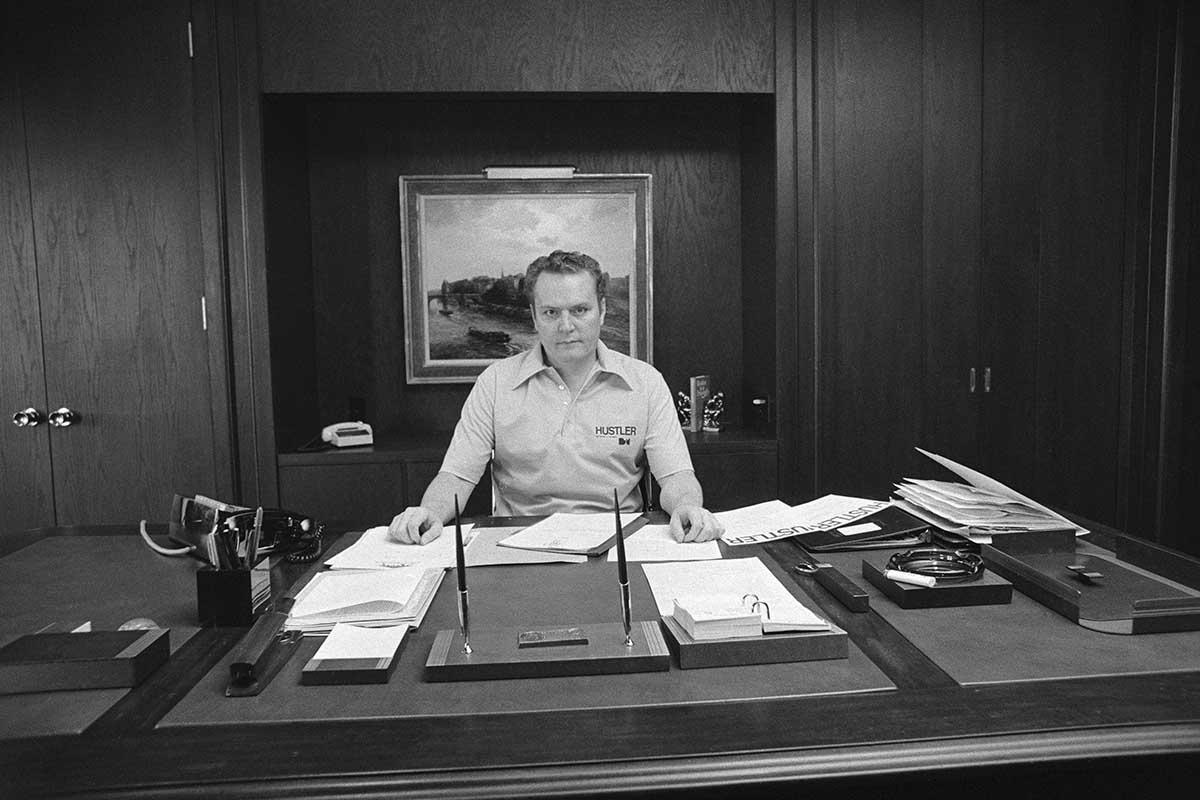

Flynt, a high-school dropout, built a multimillion dollar adult empire that started with magazines (not all adult, either) but eventually included casinos, movies, strip clubs and stores. He broke conventional pornography taboos (the so-called “pink shots”) and bought and published racy pics of former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. While his aesthetic could be considered more honest than the pretentiousness of rivals Playboy and Penthouse, his photos often devolved into pure shock factor and even depictions of violence against women. His antics in court included wearing an American flag as a diaper. And, more recently, he offered $10 million for evidence that would lead to former president Donald Trump’s impeachment (Flynt was a self-proclaimed progressive; it would be hard to pin any modern-day label on him).

But it was his battle with Jerry Falwell and the Religious Right over a 1983 ad parody (that oddly had the religious leader promoting Campari and discussing his “first time” with his mom) that cemented Flynt’s role in popular culture. A few years later, the Supreme Court unanimously rejected the reverend’s lawsuit regarding malice, a victory for free speech and (admittedly bad) satire. Flynt’s life and the court trial were later dramatized in the Oscar-nominated 1996 biopic The People vs. Larry Flynt.

I interviewed Flynt in early 1997 before his A&E Biography episode debuted. “I try to show what people really want,” he told me over the phone, his voice a bit strained. “I want to give them all or nothing.”

He also defended himself. “When people come to my office and talk to me, they always say, ‘I expected to find someone different.’ My whole image is distorted because of what I do.”

Which is what?, I asked. “A nice guy.”

Fittingly, he also reflected on his legacy. As Flynt told me: “I want to be remembered as someone who tried to make a difference.”

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.