In the second decade of the 20th century, three men embarked on a series of road trips before road trips had become ubiquitous. The names of those three men? Inventor Thomas Edison, automotive pioneer Henry Ford and writer John Burroughs. (Sometimes they were joined by others in their orbit, notably Harvey S. Firestone of the tire company that bears his name.) The three men traveled across a changing country in a changing world, and the influence of their journeys could still be felt years later.

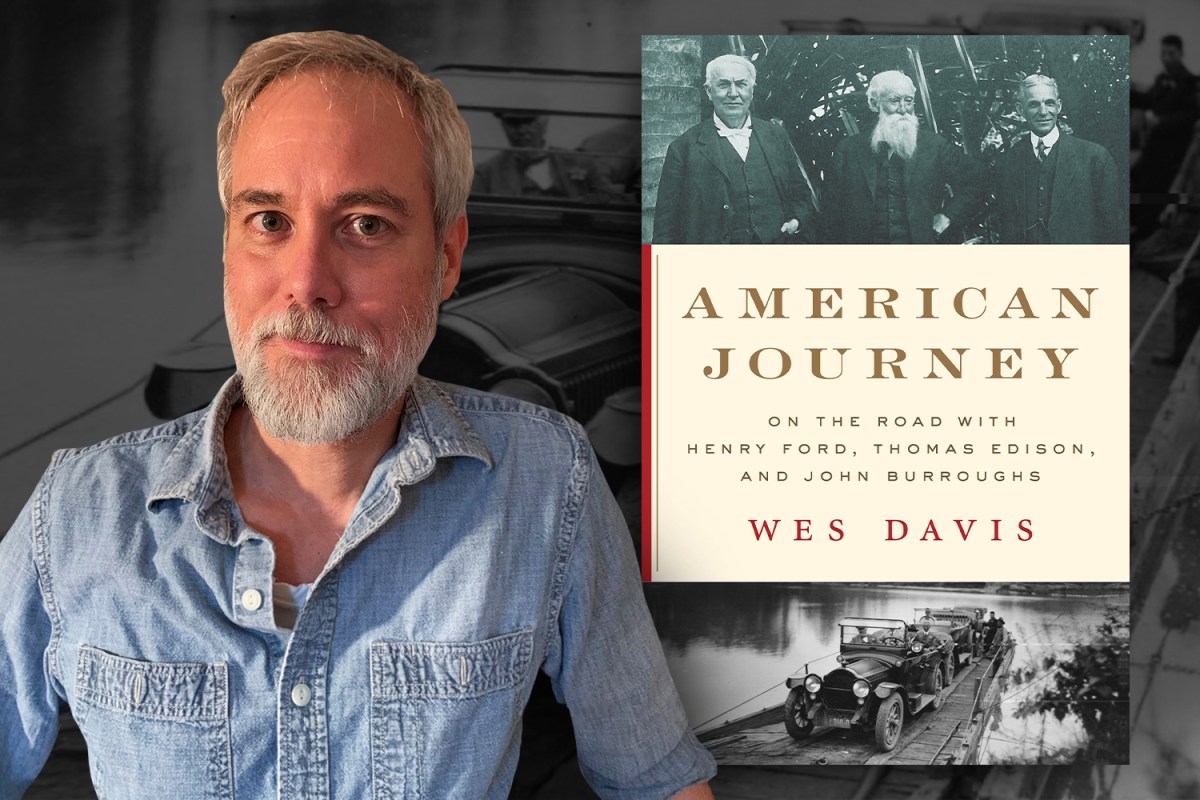

In his new book American Journey: On the Road with Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and John Burroughs, Wes Davis explored the trips that these three friends took together. The narrative covers plenty of ground, from the group’s connections to the likes of Walt Whitman and Theodore Roosevelt to the meticulous rules Edison set for himself and his traveling companions. And, in describing how Ford’s thoughts were overrun by antisemitic conspiracies, Davis also chronicles some of the fissures that developed among the three men.

InsideHook spoke with Davis to learn more about the genesis of this project, the origin of road trips and how one traveled the country at a time before road maps were ubiquitous.

*This interview has been edited for length and context.

InsideHook: The subtitle of your book references Henry Ford, Thomas Edison and John Burroughs, and I feel like Burroughs himself is much less well known in 2023 than the other two. How did you first come across him and, through him, this unlikely friendship between these three men?

Wes Davis: First of all, you’re exactly right. He’s certainly not remembered today in the way that Ford and Edison are. But in fact, he was my pathway into this story. He was, by the beginning of the 20th century, among the most popular writers in the country. I think he had two dozen books out by the time Ford met him. These mostly had to do with the natural world.

His first book was called Wake Robin. The title is taken from a flowering plant that flowers in the spring just about the time robins returned to the Northeast where Burroughs lived. He was quite popular, especially among schoolchildren, because a number of his essays had been incorporated in a series of readers that students used in their classes. So wherever he went, schoolchildren would line up to get a look at John Burroughs, who was this figure they all knew.

His roots actually stretch deep into the Transcendentalist movement in the middle of the 19th century. So he was a very close friend of Walt Whitman. They met when Whitman was living in Washington, D.C. during the Civil War and trying to help wounded soldiers. Burroughs wound up moving to D.C. at the same time, and they crossed paths — literally. They were both great walkers. And they were out separately for walks one day, met up, went for a walk. From there, this friendship developed. Burroughs wound up writing one of the earliest books about Walt Whitman and wrote two books about Whitman eventually.

The other great figure in Burroughs’s life is Ralph Waldo Emerson, on whom Burroughs very closely modeled his early style. And in fact, when Burroughs’s first major essay was published in the Atlantic Monthly, this piece called “Expression,” he sent it in and the editor of the Atlantic actually got in touch with Ralph Waldo Emerson because he thought maybe this writer he had never heard of had lifted this from some Emerson publication. And Emerson said this is not my work, but this is a smart young man. He writes like me. So that piece came out and — are you familiar with Pool’s index? Have you run across that?

I’m familiar with the term.

Yeah. So Pool’s index was this catalog of periodical literature that was published throughout the 19th century. And Pool’s index actually listed that Burroughs essay as being by Emerson. It continued to be attributed to Emerson for many, many years. In fact, I looked in a Pool’s index when I first started this project, and I found it, attributed to Emerson. So that’s where Burroughs starts. I think he recognized that he was perhaps too closely aping Emerson. So he began to develop his own style, which is much more closely focused on the actual details of the natural world. Emerson always, you know, wants to turn everything into a kind of allegory. And Burroughs goes in the opposite direction and looks closely at the actual world.

Is Burroughs still read today at all?

He certainly has his following among readers who are interested in environmental issues. Burroughs traveled in the wilderness with Teddy Roosevelt and wrote a book about that — actually, he wrote a couple of books about various travels with Roosevelt. I think those are read because people are interested in Roosevelt. But probably Burroughs’s readership has declined.

He’s the figure who hooked me into this story. I’ve been interested in him since I was quite young. I was a young teenager when I encountered his books because I had a friend whose name was John Burroughs, although spelled differently. And I liked going to this friend’s house because his family had quite a good collection of books. They had Professor Elliot’s five foot shelf of books, that collection that Harvard Press put out of great books. And they also had, because of the happenstance of having the same name, early books by John Burroughs. And so I borrowed those books; I borrowed Burroughs’s first book, Wake Robin, and Plutarch’s Lives from that collection. And so, in any case, I’ve been reading Burroughs for a long time.

I’m very interested in literary history and the correspondence of writers. So I was digging through his letters and I found this letter from December 1912 in which he’s telling a friend, “Mr. Ford of automobile fame is an admirer of my books.” And he reveals that Ford wants to send him a Model T. And so I started digging into this story. I had to find out what this is all about and wound up unraveling this whole story that comes out in the book.

In American Journey, you mention that some of Henry Ford’s children were embarking on journeys of their own during the same time Ford, Edison and Burroughs were on the road. Was the idea of a road trip still a fairly new thing, or was it something people had begun to do as soon as there were cars with any kind of range for it?

It was certainly getting started. The earliest transcontinental trip I know about is around 1903, and you have a couple of trips in that era. But you have to remember that roads were not really constructed yet for long-distance travel. So if you’re inside a city or in the vicinity of a city, roads can be quite passable. But between cities, they sort of diminish, often covered in dirt and then down to wagon tracks in some cases.

Despite that difficulty, the road trip as a concept was getting going. And it’s kind of amazing to learn that Edith Wharton, who we think of as this novelist of high society, published a book in 1908 called A Motor-Flight Through France, in which she took a car trip through France. And that’s fascinating for two reasons. One, in the beginning of that book, she says that the automobile has restored the romance of travel, which is the opposite of what we expect. But what she meant is that the automobile allowed you to enter a city the way you might have entered it in a carriage in the 18th century, whereas through the end of the 19th century and up to that moment she’s writing about, you would enter a city through the railway station. And those were often built in industrial parts on the fringes of cities. It was quite different from sort of rolling into town on the main street in a carriage. So in that sense, she has a point.

But what’s interesting is that her book almost never mentions the automobile after that. What she gives us is very much sort of the old 19th century grand tour, European travel narrative. As far as I know, it isn’t until Emily Post publishes her book about a transcontinental trip from New York to San Francisco that you get something that, at least in literary terms, looks like what we think of as a road trip.

This is Emily Post, the etiquette maven. But this is years before she takes up that role. And I think she was a struggling novelist who decided she wanted to make this trip. And all of her friends in New York tell her there’s just no way you can do this. And they start saying, you’ll have to have a chauffeur, you’ll need a mechanic — and even then it’ll be difficult. You have to make sure you take a revolver because it’s going to be dangerous out there. And she takes off and winds up making this trip.

As I say in the book, at that same time, Ford and Edison are traveling out to San Francisco. This is the summer of the Panama-Pacific Exposition, and the whole country is leaning towards San Francisco. So they travel out there by train. They had a great trip, but I think it’s the stories they then got from their children that started to stir up this idea that the older generation should embark on some of these road trips, too.

One of the most memorable details, for me, was that Edison had these very strict rules about what a road trip should consist of and what camping should consist of. Could you talk about that a little bit?

First of all, I’ll say that Edison created all of the itineraries for these trips. He planned the routes. He would contact — or have one of his employees contact — the Geological Survey Office and get very detailed maps of the areas they were going to travel to. And he used a guidebook called the Automobile Blue Book.

I was actually able to track down copies of these books from the years of their trips, which I thought would be background reading for me and would give me a sense of atmosphere. And it turned out that by combining other information from archival sources, I could see in these guidebooks exactly where Edison was going. I could follow them almost turn by turn. It was incredible.

One of his goals was always to get into the most rugged terrain. He wanted to really embrace the real wilderness whenever he could. And he also wanted the atmosphere of the trip to reflect that engagement with wilderness. So he vowed never to sleep indoors once these things had started. He didn’t believe in shaving once these had started. And at one point, someone asked him in one of the towns they passed through, aren’t you in need of a shave? And he points to Burroughs, who has a beard tumbling down to his chest and he says, “Burroughs doesn’t have to shave — why should I?”

I think this was in 1916, when Firestone and Edison showed up at Burroughs’s farm up at West Park on the Hudson. They expected Burroughs to travel with them on this trip up through the Adirondacks and across Lake Champlain and down through Vermont. But they arrived, and Burroughs says that he doesn’t want to go — he’s feeling too old, he doesn’t have the energy to do this. And Firestone, who has brought a chef who works for him at one of the Firestone facilities, has the chef cook up this really scrumptious meal. After the meal, Burroughs announces, “Okay, I’ll go, I’ll go.” The food sways him.

I bring up that evening because even there at Burroughs’s house, Firestone and Ford were camped in the yard by the house. Firestone comes in to do his ablutions in the evening. Edison, even in that moment when the trip has not really begun, he won’t go in to use the bathroom. He stays outside. Firestone was of a different bent. I think Firestone really enjoyed these trips, but he didn’t have the same stringent rules, though he knew Edison had them.

I’m thinking of one night in particular, on the 1918 trip, when it had been quite cold the night before and it was decided that it’s going to be very cold again. It’s decided that Burroughs, who’s having some ailments, maybe can’t withstand that cold. And so Firestone takes him into a nearby town to find him a room. And when Firestone sees the rooms and the baths they have, he can’t leave. So he stays there, he gets a shave, spends the night and the next morning takes Burroughs back to the place where Edison and the others are camped by this river. And Edison takes one look at him and says, “Dude.” Which in Edison’s vocabulary is the most profound insult. It’s this over-addressed city person who doesn’t know how to handle the wilderness.

You were talking a little earlier about the Blue Book. Can you talk a little bit about what that would entail to someone who hasn’t necessarily seen one in an archive?

They’re very strange. They’re incredibly thick books, and they’re printed on paper that the Bible is traditionally printed on — a very thin paper so you can get lots and lots of pages in there because there’s just so much information that needs to be imparted. You have to remember there’s very little signage outside of cities because there’s just no real tradition of travel between cities, except maybe by farmers who are taking their harvest to the mill or whatever, and they know where they’re going. So these books have to be very specific.

There are hundreds and hundreds of different itineraries listed that will get you from one place to another. For example, they give mileage, so you have to track the odometer and it will say, “At this crossroads you’ll see a stone trough, you want to turn left there.” It also gives you conditions of the roads — “So there’s a good gravel road for a mile and a half, at which point it turns to dirt, and there are switchbacks going up the mountain.” Even down to the level of telling you what the bridges are made of: “At this point you want to cross the iron bridge, and there you’ll cross the wooden bridge.” They’re fascinating documents.

Can Thomas Edison’s Reputation Be Salvaged?

The late Pulitzer Prize winner Edmund Morris explores the enduring appeal of mercurial geniusesI was impressed by some of the historical connections here. In Burroughs, you have someone who was close to the Transcendentalists and Walt Whitman. But later in the narrative, a young Dwight Eisenhower shows up. I tend to think of Whitman and Eisenhower as occupying very distinct periods of American history, and your book points to the connections between them. Was that something you were aware of beforehand? And were there any other unexpected historical connections you found when putting the book together?

I would not have put Walt Whitman and Dwight Eisenhower together before starting this project. And so you wind up with seven degrees of John Burroughs — how many people can he connect? I did know a fair amount about Burroughs, but one thing that surprised me is that Burroughs actually knew Oscar Wilde.

Now that you say it, that makes sense.

I mean, it makes sense in the sense that they are both writers in the same era. But if you think about the spectrum of authors, I think they would be just about as far apart as you could possibly put two people. And yet, they seem actually to have gotten along. Wilde said about Burroughs that he looks like a farmer but he speaks like a philosopher. I mean, he made his living working as a farmer at Riverby, his house on the Hudson.

Wilde was telling someone about this meeting and said, “No, he’s this intelligent, interesting man.” And then, finally, he couldn’t stop himself. He said, “I would like to take him out to buy some new clothes.”

Reading American Journey, I kept trying to imagine what would happen if comparable figures from today decided to get in a couple of cars and drive across the country — how much of a logistical and media circus it would be. It was an interesting way of looking at how celebrity has shifted.

I feel like there would be insurmountable security issues today — that the people who are responsible for keeping somebody like Elon Musk safe would just not allow this to happen. I think it’s very difficult to imagine.

In the book, I build up to the 1918 trip. So I follow Ford and Burroughs up to Concord, Massachusetts, where they explore Emerson’s world in 1913, and then down to Edison’s house in Fort Myers where they go camping in the Everglades, which is quite an adventure itself. And then there’s that trip I mentioned up through the Adirondacks.

My culminating point is this 1918 trip into the Smoky Mountains, which all of these people in later years would point to as the best trip they ever had. With Burroughs, they have one more trip in 1919 through New York, through the Adirondacks again, and I use that as a sort of epilogue to reflect on what these trips meant to them and what the historical outcomes were. Burroughs dies in 1921 and the trips continue. Ford, Edison and Firestone continued to travel together up through about 1923.

But those trips become more like what you’re imagining would happen today. They’re huge media events, with motion picture cameras following them everywhere. More members of their families become involved; the caravans get larger and larger, reporters are following them everywhere. Calvin Coolidge takes part in one of these, Warren G. Harding is involved for awhile in one of them. Firestone brings some saddle horses along on one, everything just explodes. And to me, it’s no longer a road trip. It doesn’t have the same interest as those ones leading up to 1918 and 1919.

In the book, you cover Henry Ford’s growing anti-Semitism and the ways in which Burroughs and Edison had to reckon with that. Ford having these awful beliefs is something that’s been fairly well documented, but what were some of the challenges of writing about that that you faced?

To be honest, that kept me from starting on this book for quite a while. I discovered the story, and I started digging into it. I saw there was a great atmosphere, that there were great stories. But I didn’t want to wrestle with that part of Ford’s character. I find it completely baffling; it doesn’t really seem to fit with other parts of his character. I almost thought I wouldn’t write this book. And then I began to discover that Burroughs was equally baffled and equally repulsed by this particular element in Ford. At that point, I realized that I could look at that part of Ford through the eyes of Burroughs, and that allowed me to work through this.

There is an evolution through this period. I tell the story early on about the trip to Seminole Lodge, Edison’s house in Fort Myers. And while the group is there, the Leo Frank case is in the news, in which a young woman had been murdered at a factory in Atlanta. Leo Frank was suspected and eventually charged with the crime. Frank was a Jewish man who had moved from New York to Georgia to run this factory, and it appeared that he didn’t get a fair trial, that he was railroaded. There were horribly antisemitic uprisings around the trial. And as it happened, as they followed this case, Ford agreed with Edison and Burroughs that this man hadn’t gotten a fair trial, that his religion shouldn’t matter, that he should be tried fairly. At that point, it seems like they all see eye to eye.

But in the 1915 peace ship affair, Rosika Schwimmer, who comes up with the idea that Ford supports, is herself Jewish. And Ford says to her, as he’s discussing this peace plan with her, that he knows what has caused World War I, and he says it’s international Jews. So he’s already beginning to move in that direction. Rosika Schwimmer must have been an amazing woman because she didn’t show that she took offense at this and instead nudged Ford along to launch this peace ship plan.

But by 1919, when the group was camped on that trip, Ford would not let this subject go and he’s constantly ranting. And there’s one night when Burroughs goes back into his tent, and he writes in his journal that Ford is ranting about Jews. He blames the Jews for everything, like the war and mounting crime and violence in the country. Edison had worked the year before for the Naval Consulting Board trying to come up with technology that would help the Navy modernize its warfare capabilities at this time in World War I — but the Navy didn’t ultimately adopt many of these things. And so Ford blames Jewish interests on this, too.

Burroughs is just fed up and so he writes, “Ford would even blame the Jews for an eclipse.” At that point, I think he doesn’t understand what’s going on with Ford — and I certainly don’t understand it. That gave me a way to push back against it.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.