It’s a great time to be a history buff. It’s also an eminently frustrating time to be a history buff. Spend enough hours online, and you’ll see why. There’s a receptive and growing audience for historical explainers and deep dives into once-obscure archives. Unfortunately, there’s also a lot of historical misinformation floating around out there, with a growing number of ways to distribute it.

What’s a responsible historian to do in times like these? In the case of Princeton University professors Kevin M. Kruse and Julian E. Zelizer, the answer involves debunking misinformation and long-standing myths. The two of them recently co-edited Myth America: Historians Take on the Biggest Legends and Lies about Our Past, which features a wide variety of contributors chronicling their areas of expertise.

InsideHook spoke with both men to learn more about the project and venture into the history of bad history in the United States.

InsideHook: Was there a specific moment that inspired both of you to put this anthology together? Or was it more of a general feeling about the current state of American politics and history?

Julian E. Zelizer: We’ve worked together before on another book, Fault Lines. Part of what we were doing was reacting to the last few years where there was a lot of stuff circulating in public about American history, including issues connected to the classroom, that we knew were at odds with what most historians have been writing about — not just in recent years, but really, for decades.

There are a lot of interesting historians who’ve surfaced in some ways in the last few years and have been writing a little bit more for the public, whether it’s on social media, op-eds or other venues. And we thought, “Why not have a book that showcases their work?” It’s short, fun and accessible essays that bring together decades of scholarship on issues that are front and center for so many Americans these days.

Were you approaching different writers and historians with topics in mind? Or did you go to them and see what they were interested in writing about?

Kevin M. Kruse: We started out by thinking about the people who were already engaging with these issues in the public sphere, often through radio and TV and especially through social media, and who had the kind of the skills we were looking for — not just really bright experts in their field, but really effective communicators.

We started with that and ran up a good core. And then we looked for topics where we had any blind spots and went to people who had expertise on those things to say, “Hey, would you consider writing an essay on this topic?” But our first priority was really thinking about getting the best people and then looking for coverage after.

Within Myth America, you cover some pretty recent events. Was it a challenge to put this book together as some of the misinformation that gets covered in it returned to the foreground in different ways?

JZ: It is a challenge in that we were putting together a book as some of the wrong narratives were gaining currency, but I think overall it energized us. Both Kevin and I would read or hear some of these things that are out there from Fox News or social media that we knew were totally at odds with what most historians have been writing about and have been discovering in the archives.

The more that we saw it and continue to see it, it really made us double down. It made us want to put this book out even more, and we’re pleased that some of the interest in and response to it suggests that there’s a readership out there that really wants to know and have a better understanding of what’s taken place in this country’s past.

If you spend enough time on social media, you can see some horrific examples of misinformation, but you can also see people being really responsive to long threads that highlight a particular moment in history. How do you see social media evolving as far as both history and misinformation are concerned?

KK: Social media certainly allowed a lot of lies and misinformation to spread with lightning speed, but at the same time, it’s given historians and political scientists and scholars a platform to push back against that misinformation. So, it really works both ways.

That’s another thing that animated a lot of us to get involved. It’s certainly become incredibly easy — and, we found out, even effective — to push back on social media against these things that Trump was saying, or that politicians were saying or that Fox News was pushing out. This is a really effective way to engage with politicians, the press and the general public, too.

Did a Romance Novelist Fake Her Own Death?

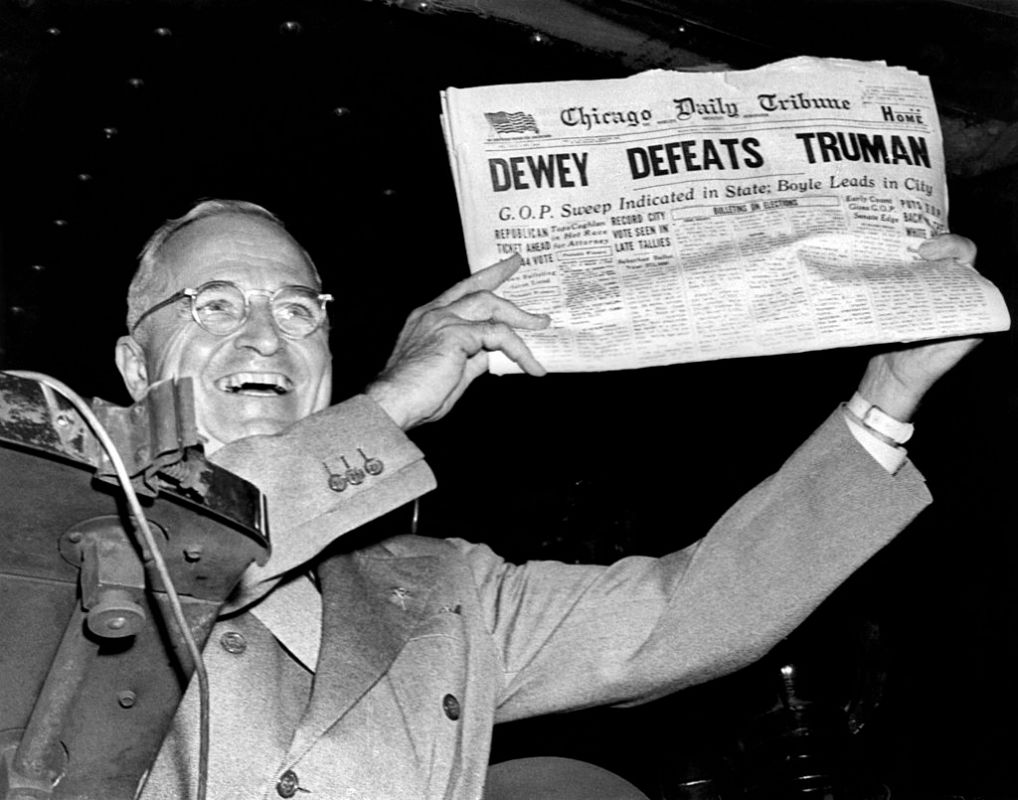

An especially surreal literary scandalBased on your own experience, would you say that misinformation is growing, or do you think there’s always been a place for it in American history?

JZ: There’s always been misinformation. In fact, historians have written about this throughout the years. Richard Hofstadter, one of the great historians, wrote about conspiracy theories in America and American politics. So it’s nothing new. But certain changes have taken place, which I think amplify how fast they can spread and how much currency they can get.

The media has changed in dramatic ways during the last couple of decades from much more partisan outlets that are willing to promote historical facts that only mesh with the stories the press wants to tell — you see this a lot on Fox News — to a kind of filterless median environment. This is one of the challenges of social media where it’s not only easy to get anything out there, but once it gets out there it can spread very quickly. Those are structural changes that I think have taken something that’s always been part of American culture and politics and amplified it.

We also talk about partisan politics a bit. Both parties certainly are guilty of having their myths, but a radicalization of the Republican party, really since the 1980s, has expanded the willingness of prominent pundits and politicians to embrace some of these kinds of arguments about American history that, again, are just not grounded in what most historians are writing about.

One of the really fascinating things that I learned from Myth America was a quote from Ronald Reagan in the 1960s talking about JFK as Karl Marx in disguise, which was incredibly jarring for a number of reasons. As editors, what came up in the essays that surprised you or that you had been unaware of?

KK: A lot of the writing in this is based on things that have been conventional wisdom for historians. Julian and I were, I think, pretty familiar with a lot of the 20th century stuff. When we got out of our own personal and professional comfort zone, I was certainly surprised by a lot of things. Take Ari Kelman’s great essay where he shows the ways that Native Americans were erased from American history in the 19th century. Things that were often seen as sympathetic to Native American culture like the famous book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee actually helped further this myth about the vanishing Native American. That was something that I think really took me by surprise. It probably wasn’t surprising to Ari and people in his field, but in a certain way, it was revelatory for me.

JZ: Another very provocative essay connected to something I talk about constantly, the idea of a backlash. It was by Lawrence B. Glickman, who teaches at Cornell. It challenges the concept of the backlash, especially in discussions of civil rights, where legislation passes or is being proposed and it stimulates a backlash because it’s gone too far.

He really questions whether that’s the way to think about what happened; rather than a white backlash, he’s talking more about a reactionary movement against civil rights, using these moments to try to expand support. But it’s not the legislation that’s causing the response, it’s a long-running movement. It’s a great essay that pushes me — and others, hopefully — to rethink a basic term that we use in American history.

How did both of you determine what you were going to write about?

KK: In a lot of ways, that was the easiest part. My agent’s been asking me for years to do something with all the threads I’ve done on Twitter. The biggest one for me is that the “Southern strategy” was actually a recent myth. As I wrote those threads, I kept thinking, “Well, I can recommend a massive tome on this.”

Earl Black has a great book called The Rise of Southern Republicans. The problem is that it’s a phone book. It’s hard to recommend to lay readers; it’s a very thick, dense read because of all the evidence inside. I remember thinking, “I wish I had something short and snappy to pass along on this,” and like most professors when we reach a point where we wish we had a reading assignment, we just give up and write it ourselves. And with Julian, I think it was the same way. He’d already written extensively on the Reagan Revolution. So this was a natural fit for him, too.

JZ: This was just something I’d been thinking about, that I’ve been working on in different ways. As Kevin said, I wanted to put together in a very short, accessible piece to really question — or at least complicate — the idea that there was this clean sweep of conservatism in the 1980s and to problematize the concept of a Reagan Revolution. And to understand the period as opposed to thinking of the Reagan Revolution as part of the politics and part of the Reagan administration’s strategy during the 1980s.

In that article, you point out that Eisenhower’s average approval rating was significantly higher than Reagan’s, for instance. Do you think there’s something unique to the American political system that allows for more misinformation and myth-making?

JZ: There’s some of that, clearly, in terms of the disconnect between what the Electoral College is saying and what the popular vote is saying. The Electoral College can give the impression that there’s more consensus in the country than there is.

It’s not simply about Reagan. It’s a way we think of the presidency. We define and shape a lot of our understanding of history around a president. And I think there’s a notion that when a president is in office, especially a two-termer, they define the era and that they commanded immense support. And they do! It’s not that they don’t. But there’s clearly a large portion of the public that are unhappy with the direction of where things are going.

The Reagan Revolution has been triply important because it’s become a staple of how we think of conservatism. We move from the New Deal-1960s period of liberalism to a shift to the right. The Reagan Revolution is a way of thinking about that. I think there are many things working all at once. And again, my essay doesn’t mean to discount Reagan’s popularity, or his importance — it’s just to put him in context and show the persistence of liberal ideas, values and institutions in the 1980s and well beyond.

Are there any other presidents who you would say have been largely misunderstood by the general public or have been mythologized to the point of being unrecognizable?

KK: You mentioned Reagan’s comments about JFK earlier. I think it’s instructive because JFK has been, in a lot of ways, weirdly claimed by those on the right as someone who would have clearly agreed with them. It’s not a myth we really addressed in the book, but I could talk about it now.

If you look at JFK’s record at the time, he was considered a liberal by those in his era. Reagan called him a radical. He thought he was Karl Marx “beneath that tousled haircut.” But if you examine Kennedy’s stances on a lot of issues — on equal pay for women, on affirmative action and on civil rights — he seems in line with kind of a liberal trajectory. But because he cut taxes once and made Cold War speeches, he’s been claimed by the Right as one of their own. It’s really kind of jarring.

As you were putting Myth America together, did you notice anything sort of changing when it comes to misinformation, or is it on a similar trajectory to where it’s always been?

JZ: We started this and we even planned a conference where the authors would present before COVID. A lot of this was written in the era of COVID — we even had a gathering that became virtual. There are a lot of people who are writing interesting things now about how COVID amplified the space of the internet and social media and everything, because people were sitting at home unable to have natural social connections. I haven’t really thought about it, but my guess is that in the time of the writing, there probably was a continued intensity or intensification of these kinds of arguments as the social media sphere gained more currency because we were living through this pandemic.

Is there anything else you’d like people to know about this book?

KK: For people going into it, I think I just say that these are essays by gifted writers and really smart scholars, written with a general audience in mind. Sometimes historians are speaking to each other in the ivory tower. But this is a group of really great writers writing for the general public. So we hope it’ll be accessible to a broad audience.

JZ: I mean, it’s a fun read. It’s not an easy read — the issues are difficult, but these are really good authors. We’re in this period where I think a lot of people have this impression of what college professors are, between the universities and the broader public. And I think these essays really bring to the forefront the work that historians are doing. We’re showcasing people who really know how to write. You can sit down and read this book pretty easily, even though you’re reading about some of the most difficult issues in American history. We hope it’s an enjoyable book in addition to being a provocative and thoughtful one.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.