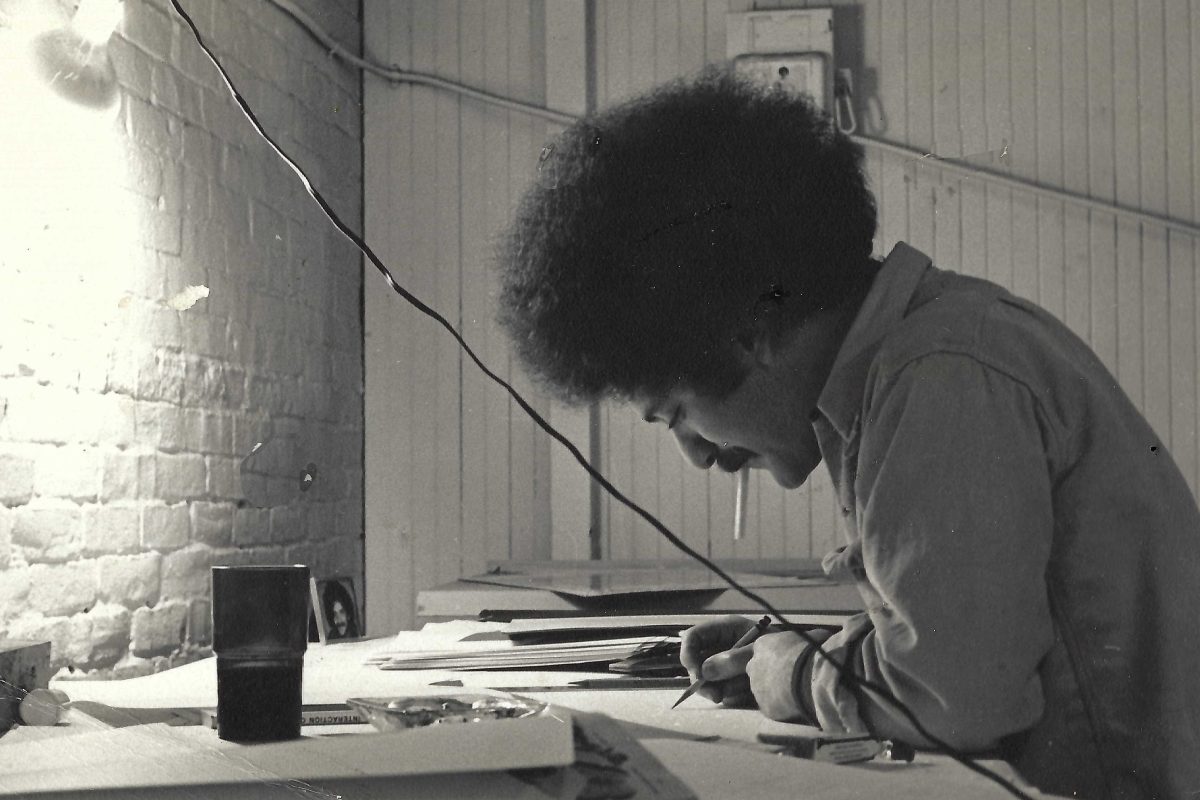

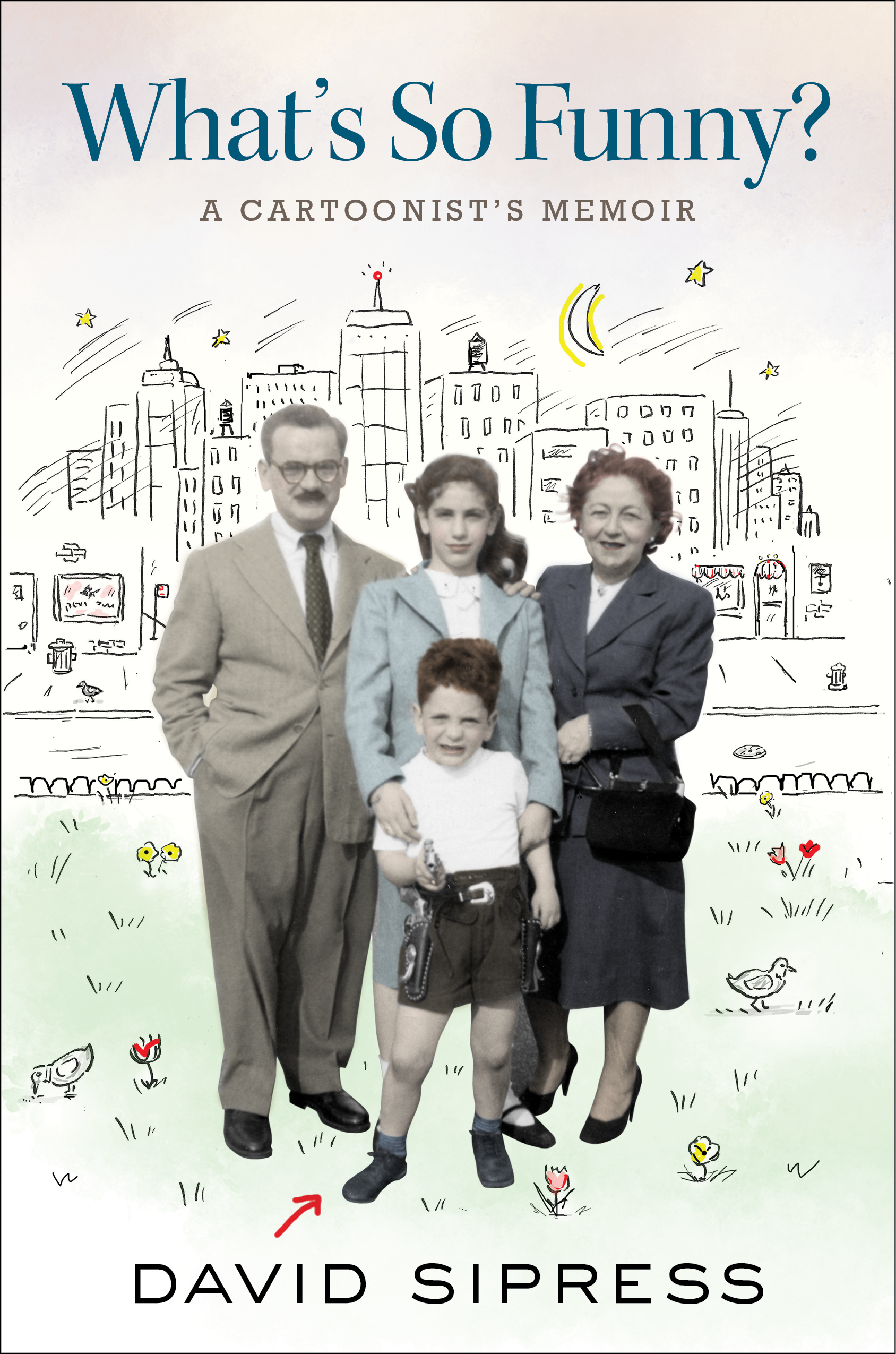

A history major who graduated from Williams College in 1968, David Sipress went on to the Master’s Program in Soviet Studies at Harvard University, but he dropped out after two years to pursue his true passion. Six months later, his first cartoon was published in The Boston Phoenix, where Sipress went on to serve as the weekly cartoonist for 25 years.

Sipress now lives in Brooklyn and has been a staff cartoonist at The New Yorker since 1998, publishing nearly 700 cartoons in the magazine. Sipress, the 2016 winner of the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben Award for Gag Cartooning, is publishing a different kind of work this month with the release of his first book, What’s So Funny?: A Cartoonist’s Memoir (out today, March, 8th). Prior to the release of What’s So Funny?, Sipress was gracious enough to speak with InsideHook about his book, the creative process and New York City.

InsideHook: How did the process of writing your book compare to the process you use for your day job?

David Sipress: I’ve been addicted to doing single-panel cartoons for my entire life. It’s the shortest form creativity can possibly take. You get an idea, draw it and put in the caption. In five minutes, you’ve done your work for the day. The idea of writing a book seemed unimaginably challenging and huge because I had never done anything long-form like that before. I felt like it was a challenge I needed to take on, to learn how to write in a way that didn’t depend on one idea at a time. That’s what got me going. On the days the writing went well, I began to realize it wasn’t that dissimilar. One good idea led to another good idea that led to another. It was kind of like stringing together the single ideas that I’ve been so familiar with for my whole life. It got to be fun and kind of addictive.

Did your experience as a cartoonist help you as an author?

Cartoons involve writing. Caption writing is a very specific kind of writing. Cartoons are a wonderful medium to whittle things down to the essential point and then get it across. The most important thing is to make people laugh. I believe that you can make a point and have it sink deep into the consciousness of the reader by making them laugh. I think that’s the special thing about these simple, little single-panel engines of truth. You learn a lot when you’ve written thousands of them. You learn how to write dialogue, how to put words in a particular order to have the greatest impact and that less is more, generally. A caption needs to be short and to the point. That’s the kind of writing I’ve always loved in the books that I read. I found there was something very familiar about the writing, especially dialogue, in the book.

How about your background as a history major and buff?

I read a lot of history, and I studied it way back when. I had to make peace with the fact that my version of my history was mine and mine alone. I knew maybe not everything I put down as history necessarily happened the way I said or is true. But it’s how I remember it and how I’ve always viewed events in my past. That’s something you learn very early when you study history. Everybody who writes history is writing it from their point of view and there’s no absolute truth about what actually happened, who won that battle, who was at fault. I was really liberated when I had read a memoir called The Pigeon Tunnel by my favorite writer John le Carré. In it, he says that memory is as elusive as a wet bar of soap and the truth that matters is not some objective truth, but your truth. What matters is what I remember and what I remember says about me. If you study history, you always have to keep in mind that whoever you’re reading is giving you their truth, not an absolute truth.

How prominent a role has New York City played in your life?

Ever since I was a child, this place excited and inspired me. I always thought of it as the place to be if you were an artist. The city is constantly informing me and giving me ideas. It’s my home and it’s my inspiration in many ways. Someone described my book as a love letter to New York. I never thought of it that way, but a lot of the stories depend on there being a New York. All of it has a New York basis. I’m still experiencing the city in much the same way I did 50 years ago. Every day when I get up and go out and walk the streets, something interesting is going to occur to me. I’m going to see something I might want to make a cartoon about or something I might want to write about. It’s a very exciting place for a creative person and it’s a place where you can form connections to lots of people who do exciting and interesting things.

Is there a takeaway you are hoping readers of What’s So Funny? will walk away with?

I hope the reader will see my story as an example of how humor can be an invaluable way to process the difficult stuff in life, including, of course, the difficult stuff with family. As I revisited the past in the course of writing my memoir, what became increasingly clear to me was that “my cartoon brain,’’ as I call it, has kept me sane and saved me over and over from taking myself too seriously. When I get anxious, worried or angry, I think up cartoons. I really can’t help myself. So when people ask that inevitable question, “Where do you get your ideas?” I can honestly say I get them from living my life. The creative process is connected to the life you live. It’s not a separate thing.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.