The alien beauty of Antarctica and those who dare venture into its cold, desolate heart have long captivated me. I distinctly recall being in awe of Ernest Shackleton, the most famous polar explorer, when I first learned about him in sixth grade. He was, as Alfred Lansing writes in Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage, “an explorer in the classic mold — utterly self-reliant, romantic, and just a little swashbuckling.” I was taken, as were many of his contemporaries, by Shackleton’s leadership as well as the all-consuming demands of his expedition. The journey required not only incredible physical endurance, but also deep reservoirs of mental fortitude and, above all, a wellspring of optimism despite brutal conditions.

Today, as we burrow still deeper into a national lockdown and deliberate about how to reopen society, I recall these stories of human triumph, draw strength from their character and lose myself in this otherworldly landscape. Though our conditions are vastly different, I believe there is value in emulating the same qualities that proved necessary to surviving in the Antarctic: camaraderie, hope and sheer willpower.

Antarctica is hostile to most life, and yet, since it was discovered 200 years ago, those who have stepped foot on the continent often return obsessed with the place. “Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons,” wrote Shackleton in The Heart of the Antarctic. “Some are actuated simply by a love of adventure, some have the keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden paths by the ‘lure of little voices,’ the mysterious fascination of the unknown.”

I too am drawn to the “lure of little voices,” and seek them out in beloved books on polar exploration, such as Endurance by Alfred Lansing, Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez, Brother in Ice by Alicia Kopf and The White Darkness by David Grann. Of these, I have reread none more than Grann’s, a slim volume detailing the remarkable life of British military officer Henry Worsley and his efforts to retrace the footsteps of his hero, Shackleton, in 2009.

Worsley modeled his life after Shackleton, who in many ways was a failure. Each of Shackleton’s expeditions fell short of their intended goal, but unlike other explorers, Shackleton and his men always made it out alive. Shackleton’s decision-making was always selfless and wise; he always put the safety and security of his crew above any quixotic designs on becoming a hero. That mentality has inspired a legion of acolytes and imitators, Worsley among them. Worsley was, in the words of Grann, that “rare apostle whose life seems to affirm his master’s teachings.”

Upon successfully retracing Shackleton’s journey with two other men, Worsley later returned to Antarctica to traverse the entire continent alone and unaided — a task never before attempted. An unsupported journey meant Worsley would travel from coast to coast on foot with no food caches and no sled dogs. Instead, he would haul a 325 lb. sled full of provisions (“nearly double his own weight,” Grann notes) across 900 nautical miles of ice. It would prove to be Worsley’s final expedition.

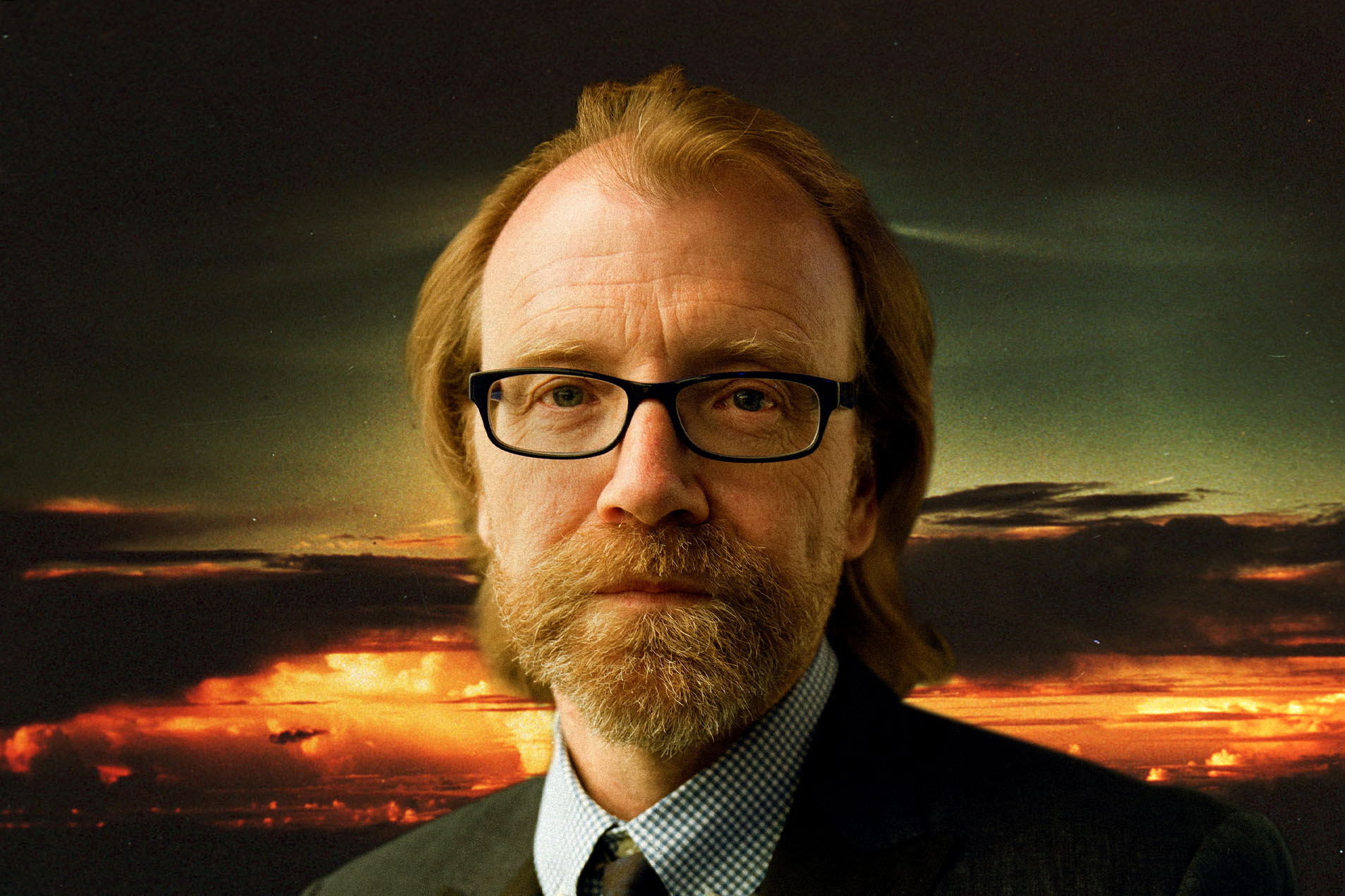

After 70 days and nearly 800 nautical miles, Worsley hit a wall. Each day had become more punishing than the last. Grann, who was granted access to Worsley’s final diaries, tells me over the phone that he could see “the deterioration of his handwriting.” “He had lost dozens of pounds. He could barely put one foot in front of the other … It wasn’t necessarily what he wrote, but the way he wrote. That loss of command over his penmanship spoke so much to me.”

Because Worsley was an “obsessive documentarian,” Grann says he “felt closer to Worsley’s consciousness than anybody I had ever written about. I often felt, because of the way he was recording his experiences hour to hour, as if I was walking beside him.”

Too fatigued to carry on, Worsley spent a day in his tent. He called his family, who urged him to come home, and deliberated what to do next. As he often did, Worsley asked himself: What would Shacks do? The following day, he called “the most expensive taxi ride in the world,” and a search-and-rescue plane was dispatched. He made it back to base, but later died of organ failure.

In many ways, polar expeditions are mythic quests. Their task is often quite simple: reach point X. As Grann notes of Worsley’s group expedition, “their grail was no more than a geographical data point,” indistinguishable from the barren ice that stretched all around them. But embedded within this physical task was a deeper, more personal one — an inward journey, if you will. “What is Antarctica other than a blank canvas on which you seek to impose yourself?” asked Henry Adams, one of Worsley’s earlier companions.

This mythic aspect of polar expeditions is bolstered by the fact that Antarctica is a vast, strange landscape born of the rawest elements: ice, sea, wind. In Endurance, Lansing describes the phenomena of “ice showers,” wherein “millions of delicate crystals, frequently thin and needle-like in shape, descended in sparkling beauty through the twilight.” Can you imagine walking through a suspended chandelier of splintered ice?

But Antarctica is as violent as it is beautiful. Technically a desert, “it is the driest and highest continent, with an average elevation of seventy-five hundred feet,” writes Grann. “It is also the windiest, with gusts reaching up to two hundred miles per hour, and the coldest, with temperatures in the interior falling below minus seventy-five degrees.” In short, Antarctica is one of the most extreme environments on Earth. One misstep and you could be swallowed by a hidden crevasse.

Worsley and Shackleton’s ability to adapt to “extreme circumstances” was, in many ways, what made them exceptionally suited for the Antarctic, a place “where the circumstances could not always be predicted or controlled,” says Grann.

“That is certainly the environment we are living in,” Grann continues, speaking of the ongoing global pandemic. “So how do you manage to endure within that environment?”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.