Either cocktail napkins are an unlikely candidate for “survivorship bias” — they’ve reportedly given us Harry Potter, Pixar, Shark Week, the Super Bowl trophy and the first model of Chicago’s grid — or there really is some magic to scrawling an idea down at the bar at the end of a night.

At some point in 1975, the same year Steve Prefontaine died, a first-year track coach at the University of Michigan named Ron Warhurst sat down for a few beers and got back up with a blueprint of the most notorious running workout ever created.

Warhurst couldn’t stop thinking about a circuit that Coach Bill Dellinger — the man who took over for Bill Bowerman at the University of Oregon — had apparently put Prefontaine through in Eugene mere weeks before the star runner’s fatal car crash. It involved running 1200 meters over and over on the track, yet, crucially, splicing each rep with a two-mile-plus tempo run on one of the trails around campus, right around a pace of five minutes per mile.

It was an extremely unconventional conceit for a running workout. For one, power workouts (track repeats) are often separated from endurance workouts (tempo runs). But the mixture of track and trail was what really got Warhurst’s creative juices going, according to a 2018 profile by runner’s journal Løpe Magazine. He started thinking how the construction could help simulate what racing really felt like, with surges that arrive at indiscriminate times, which have to be run on legs that logically shouldn’t have anything left.

So, naturally, he leaned into the illogical route and created “The Michigan,” a notorious circuit that’s been idolized (and bastardized, into countless similar forms), by coaches at the prep, collegiate and professional levels for the last five decades.

Here’s what it looks like:

- Two to three miles of warmup

- One mile at 10K pace on the track

- One mile at 5K pace on a trail nearby

- 1200 meters at 5K pace on the track

- One mile at 5K pace on a trail nearby

- 800 meters at 5K pace on the track

- One mile at 5K pace on a trail nearby

- 400 meters on the track, with whatever you’ve got left

For those looking for a hand on the mathematics, that’s five and a half miles of running, plus a couple miles for the warmup, for nearly eight miles total. But the mileage isn’t what makes The Michigan so feared or respected. Big-time runners are accustomed to long workouts. It’s that the workout acts as a stand-in for the most competitive runner you’ve ever faced — it doesn’t care who you are, or where you are in the effort. It demands sudden bursts of intensity without announcement or fanfare, before spitting you right back to a baseline pace that’s mildly torturous.

When Warhurst designed The Michigan he reportedly tried to get into the brain of “a runner who felt good.” For every runner whose internal dialogue invokes the common-sense questions and equations of racing (like: Am I saving enough here? Maybe I’d be better served making my move in 800 meters?), there is a pack-leader who could care less. They will drop the hammer whenever, if that’s what it takes to drop everyone on their tail.

Prefontaine quotes turned pastiche a while ago, but his words continue to offer an inlet into the minds of stud runners: “The best pace is a suicide pace, and today looks like a good day to die.”

Some of Warhurst’s best runners — guys like Kevin Sullivan, or Nick Willis, both of whom went on to compete in the Olympics — took to The Michigan with this level of intensity. Finally, a worthy opponent. But the trick (and the genius of it all), is that they’re really just locked in a battle with themselves.

I have significant track workout experience. I’ve been running them off and on for the better part of 15 years. Somehow, though, I’ve been spared of ever running The Michigan. Earlier this month, I decided that needed to change, and I found the courage to attempt the workout on a temperate Tuesday. I use the word “attempt,” because I’ve long read horror stories of runners DNF’ing with several reps to go.

Walking away from a workout is understandable if you’re nursing an injury or succumbing to the heat. It implies that you physically couldn’t finish the circuit. But leaving The Michigan is different; it more specifically means you couldn’t hold on to the pace any longer. You could finish, at a minute or two slower per mile, but what would be the point in that? This is a workout designed to destroy. Once the pain overrides your ability to accept (and even embrace) that premise, you might as well call it. To be clear: that’s nothing something to be ashamed of, it’s just a fact. The Michigan is not a marathon you fundraised or traveled for. No one is necessarily watching. You can always attempt it again. If your first try results in running so hard that you can’t finish, that’s a bizarre, drunken victory in itself.

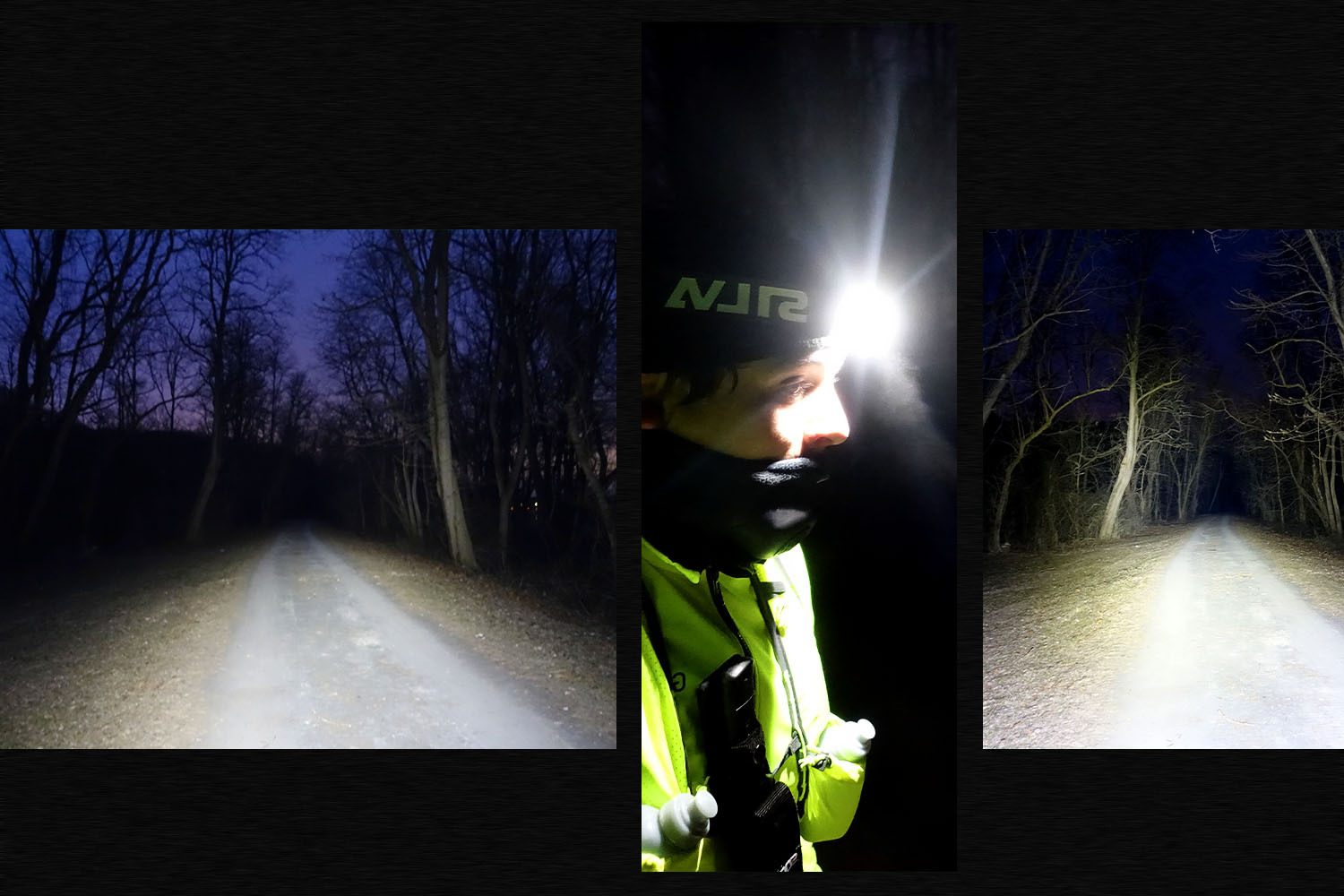

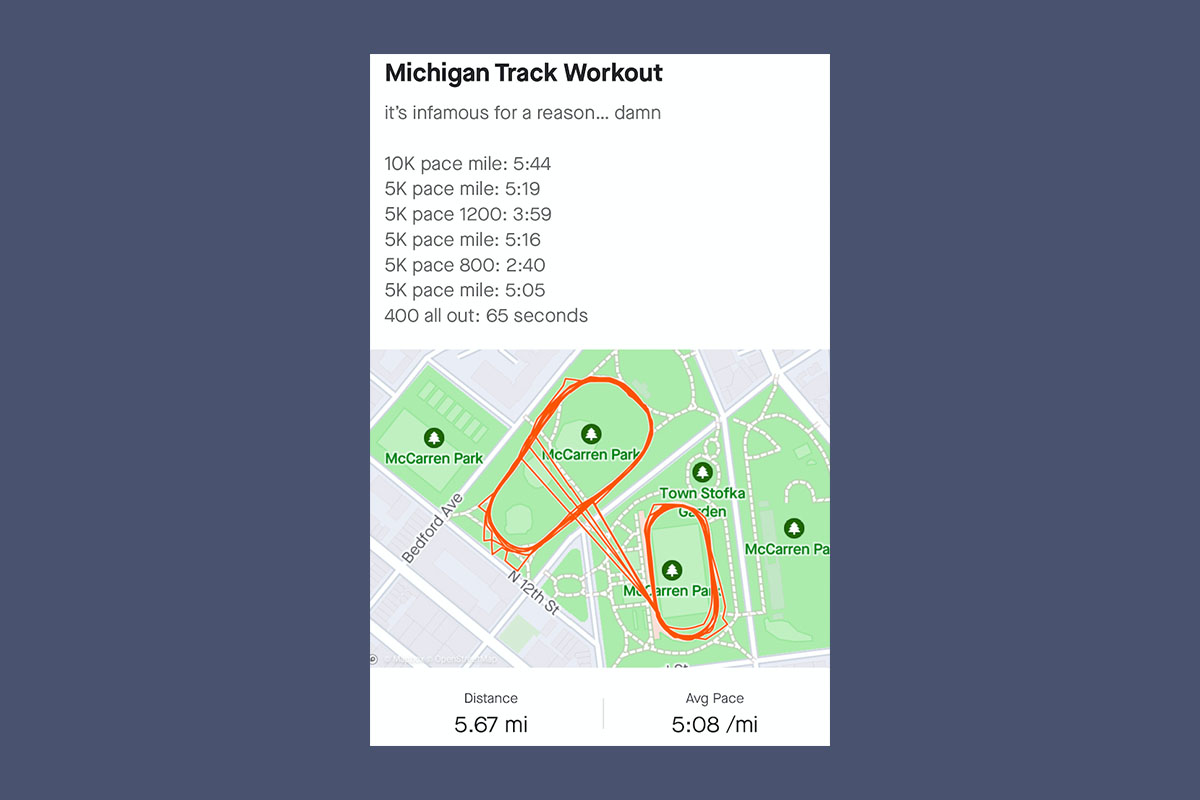

Fortunately, I was able to complete the workout last week. I ran it at McCarren Park in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood, a convenient location not just because I live around the corner, but mainly because it includes both a fantastic track and a park with a public path. I could filter between track and trail without any hassle.

I’ve had to run some humdingers over the years. One of the worst ever was 400-meter repeats (20 of them!) paced by a guy who had run for the University of Miami. You’ll find yourself in a very dark place during conventional, “counting” track workouts. But at least your body has a chance to settle in; the pain becomes familiarized, almost automatic, until the last few reps of the entire workout, when the top guns start separating from the pack, and you do all you can not get embarrassed.

In contrast, The Michigan is schizophrenic by nature. It darts between specific forms of agony. Not once in my workout did I feel “settled.” There was too much think about, and especially because I was doing my own pacing. Plus, my goals were steep:

- One mile at 10K pace on the track: 5:45

- One mile at 5K pace on a trail nearby: 5:25

- 1200 meters at 5K pace on the track: 4:00

- One mile at 5K pace on a trail nearby: 5:25

- 800 meters at 5K pace on the track: 2:40

- One mile at 5K pace on a trail nearby: 5:25

- 400 meters on the track, with whatever you’ve got left: 65 seconds

If you take a look at my Strava data above, I did manage to meet or sneak under every goal time. It was the hardest running workout I’ve ever put my body through. It’s somewhat shocking to me, after running for so much of my life, that I can confidently say that. But there’s no recency bias here — no workout has ever asked me to do so much on tired legs. If I had to pinpoint the exact time they died, I’d say the second lap of the 800-meter run on the track. I barely met my goal time of 2:40 (a 5:20 mile pace), and couldn’t fathom running another mile out on the terrain.

How did I run a 5:05, then? And manage a 65 for the final 400? I don’t really have an answer, and I’m okay with that. Races (like most forms of performance) thrive on exhausted improvisation. The Michigan has an uncanny capacity for hacking into that mental wiring, and coaxing out the character you need to assume in such situations. Plus, at that point in the workout, the physical and emotional investment is off the charts. If you think there’s a chance you can do it, why quit with one mile left?

Warhurst, who is now 76 and retired, and years ago bequeathed Michigan’s track program to one of his pupils (the aforementioned Sullivan), has a pair of amazing quotes on what it feels like to run The Michigan. The first: “It’s not a bee sting. It’s a steady thing that keeps coming at you. It’s a toothache, a grind. But you can function with a toothache. It’s an annoyance, but you can’t feel sorry for yourself. You get through it, and when you’re done you feel like you climbed Mt. Everest.” And the second, TL;DR version: “It’s like eatin’ dirt and spinach.”

Some lasting impressions from my first Michigan: I found the intervening tempo miles harder than the track shifts. This is different for many college stars and pros, who purposely hammer their track times well below 5K pacing, in an attempt to knock out world-beating splits. The workout is infamous enough that they can send those numbers to runner friends without explanation, and they’ll understand what they’re in reference to. For my part, I stayed on task while on the track, and struggled more with the mile intervals (which also, I should add, took place on uneven ground). Why? In dopey terms: it was just a long time for me to be running so fast.

In an age of carbon-plated shoes and lightweight spikes, The Michigan creates an equipment conundrum. There isn’t much rest in between sets (I am confident I was milking time that no NCAA coach would’ve granted; there was at least a few minutes separating that catatonic 800 and my final tempo mile), and you’re basically jogging straight from the track to the park. That means definitely no spikes, and based on the terrain — roots and rocks can have their way with a racing shoe — maybe no $250 Nikes, either.

I was lucky this part of Brooklyn has zero elevation gain. I can’t imagine finishing The Michigan the way I did if I had to worry about a hill. This wouldn’t be as triumphant of an article, let’s leave it at that. But that also speaks to the endless cruelty versatility of the workout’s design. You could put the tempo on a hilly course map. Or add another mile and a 200. Or attempt it on a windy day. The basic idea remains the same: no workout is going to force the body to change speeds, recruit different muscle fibers, push your VO2 max, build strength, melt your brain, or test your mettle quite like one jotted down on a cocktail napkin, 50 years ago this year.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.