Barry Bonds owns a ton of insane baseball stats. He’s the game’s home run king, he’s fourth all-time in WAR (there isn’t a single other contemporary batter in the top 15) and he’s got seven MVP awards on his mantle. When he won his first, George H.W. Bush was president. When he won his last, George W. Bush had just been elected to a second term.

My favorite of all the stats, though, is his all-time record for IBB (intentional bases on balls). It’s an imperfect, incomplete stat, in that MLB didn’t officially start tracking it until 1955, but Bonds’s command of the list is so absolute that I find it difficult to even care. The retired slugger was intentionally walked 688 times throughout his career. Albert Pujols is second-ever with 315. The rest of the top names — Stan Musial, Hank Aaron, Ted Williams — all came in below 300.

What more proof could you need that a hitter was respected (RE: feared) than the fact that nobody wanted to pitch to him? Buck Showalter, one of the proudest managers in baseball, once infamously walked Bonds with the bases loaded — in the bottom of the ninth, with two outs, in a two-run game. The ploy worked, and his Diamondbacks finished the game with a 8-7 win, but the messaging was clear. We’d really rather not let this happen.

Bonds missed out on his last chance to make the Hall of Fame yesterday. The writers blew it. Bonds has been eligible for induction since 2007 (the old rules allowed 15 years; he and other stars were grandfathered into 2014’s 10-year revision), and despite younger, more open-minded voters joining the BBWAA, more than 25% of the association’s ranks refused to allow a Bonds plaque in Cooperstown. If he ever makes it, it’ll be through the Today’s Game committee, a sort of “our bad” system, where a group of 16 electors vouch for players between the years 1988 and 2017 who slipped through the cracks. Bonds will need 12 votes, and will likely fall short in his first shot this December.

We know why he didn’t get in the conventional way, obviously. But we don’t know why Bud Selig, the man who oversaw MLB’s most contentious era, had no trouble getting into the Hall in 2017. Or why more recent eligible ballplayers with links to performance-enhancing drugs (David Ortiz) have an easier shot at getting in during their tenure. Or why we’re okay with the passes that were given to ’50s legends who scooped amphetamines like Skittles before games, or the many enshrined names of players and coaches who sexually assaulted women or sympathized with the Ku Klux Klan.

The Hall of Fame — and its attending voters — isn’t a sham. But this obsession with its perceived “purity” certainly is. If the museum were actually a library, then Barry Bonds is one of the most-read books of the last three decades. What are you going to do, not stock it because the author was indicted on perjury charges once? If anything, that makes for a better story. Jeff Passan summed up the news well in a story for ESPN yesterday: “Really, maybe it’s just as simple as the guy with the most home runs ever should be in the museum that exists to tell baseball’s story.” Your stated mission is to preserve history. So preserve it. Home runs, intentional walks and all.

So. How is Barry Bonds taking this news? Unclear. He’s definitely had a long time to process the fact that he might not have an induction ceremony. That said, we do have one telling look into his life, and it suggests that the now 57-year-old may have found some post-retirement peace. Bonds, believe it or not, is now a prolific cyclist, who lives a bucolic existence in the foothills of Marin County.

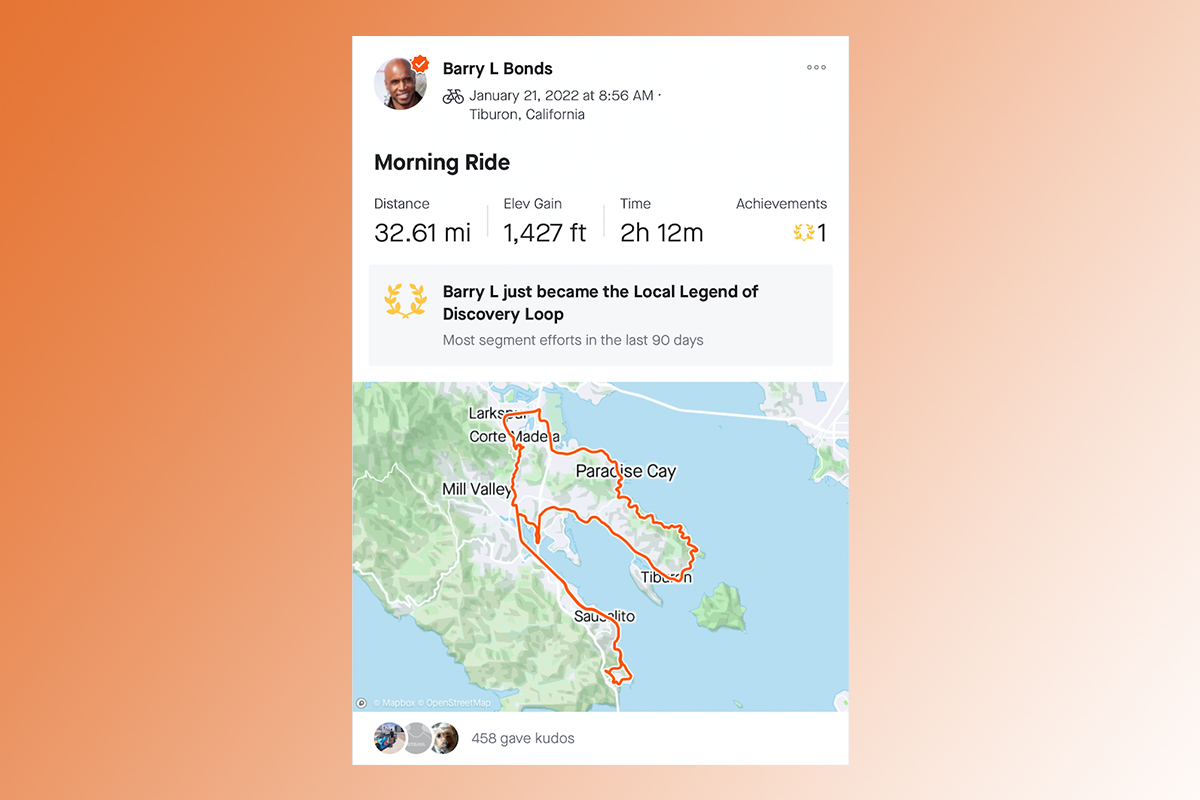

That’s right — the man who once made a living hitting moonshots into San Francisco Bay now spends his days biking around that bay, most recently on a Tarmac SL7 from Specialized. It’s a true cyclist’s bike, beloved by pros for its speed and comfort, with a price-tag over $12,000. Bonds likes to start his route in Tiburon, follow the water, cross Redwood Highway, then loop down past Mount Tamalpais, Tennessee Valley and Sausalito before returning to Tiburon. He records all of his adventures on Strava, via a Garmin watch, and it’s customary for hundreds of fellow riders to “kudos” these routes, or even leave a comment.

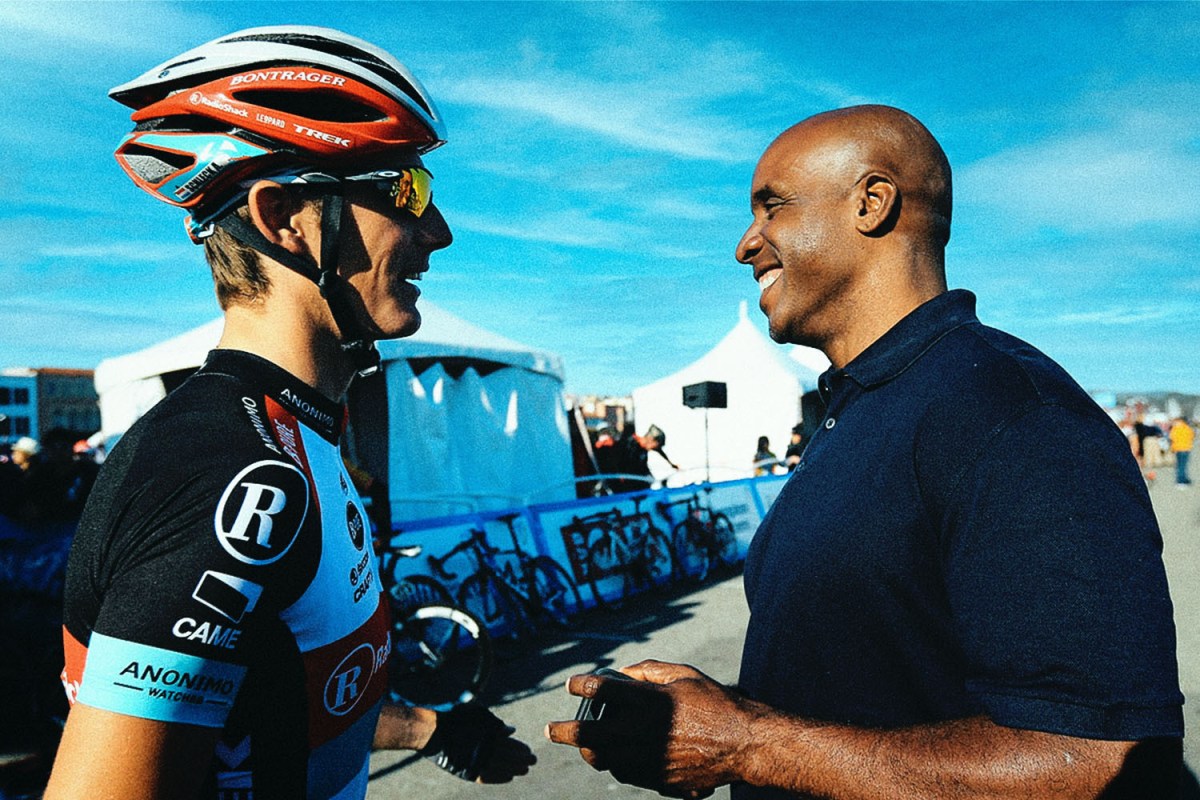

Just a few days ago, a cyclist quietly commented on Bonds’s 36-miler: “Thank you for showing me the route.” Bonds replied: “It was great to meet you and you are welcome.” They’re now following each other on Strava. Earlier this week, another cyclist wrote: “I hope you get the 75% Barry. You deserve to be in the Hall. I met you at Interbike years ago and you took the time to chat with me for a few minutes about baseball and bikes. Thank you! Good luck.”

Chance run-ins and well-wishes for his Hall of Fame status … both appear to be a common refrain in Bonds’s feed. Bonds also tends to pick up admiration whenever he completes a particularly difficult local route. A couple weeks ago, after logging a notorious 23.5-mile out-and-back that finishes with a 13%-grade home stretch footpath, a follower commented: “Congrats! Mt. Diablo is a beast.” Mt. Diablo is one of the most iconic climbs in the Bay Area, usually showing up on the “top three” or “top five” lists of local bloggers. Point being: Bonds is legit. He loves this community. He belongs in it.

In fact, he may have been so successful in creating this second life that some in the area fail to realize he’s that Barry Bonds. This past December, a Strava user reached out with an invitation: “Hey there Barry. I frequently check out the leaderboards where I ride to see who’s near me. That’s you. I’m part of a bike club. We’ll be doing the Paradise Loop in March … We MTB and road cycle. Check us out and maybe come ride with us. You’ve got the same name as a sports fella, cute. Cheers.”

There’s something oddly morbid about baseball. The Cooperstown plaques are tombstones, the induction day speeches are eulogies. There’s a sense that your career happens, and then you die. Maybe you come back as a coach or manager, or work in the front office. But you’re decomposing at that point. Your powers are gone, your body’s withering away. You’re a fading star.

In an interview with ESPN Magazine in 2015, Bonds said the following words: “I may have my problems, but I’m not dead. And this is a good thing.” He was referencing the steroids of it all — the BALCO investigation, the obstruction of justice conviction that was overturned, the chance his extremely public trial would make it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. But he was also channeling hope. He wasn’t dead. There was still time, and plenty of it. Maybe not enough time to change people’s minds about what they thought about Barry Bonds, or what they remembered, but time enough to change his own.

During a “teary-eyed soliloquy at his 50th birthday party,” which featured a “cake molded into the shape of a mountain with the figure of a rider at the base,” Bonds told friends and family that cycling saved his life. He repeated the claim to ESPN. “Cycling took me away from a lot of pain I was going through, a lot of personal problems,” he said. His favorite photo is one taken during the midst of his three-week trial in 2011. It was the first time he rode across the Golden Gate Bridge, and the only time during that period that he felt stress-free.

As the 2010s wore on, and Bonds racked up miles, his bristly attitude appeared to soften. In an interview with the veteran sportswriter Terence Moore, he tried to explain how things had fallen apart to begin with: “I’m not going to try to justify the way I acted toward people. I was stupid. It wasn’t an image that I invented on purpose. It actually escalated into that, and then I maintained it. You know what I mean? It was never something that I really ever wanted. No one wants to be treated like that, because I was considered to be a terrible person. You’d have to be insane to want to be treated like that. That makes no sense … ‘So I just said, ‘I’ve created this fire around me, and I’m stuck in it, so I might as well live with the flames.’”

It took a while, but cycling helped Bonds get his mind right. It transformed his body along the way. Bonds has lost at least 25 pounds from his playing weight since he started cycling. During his first ride, in 2010, on the path between Malibu and Redondo Beach down in Souther California, he said a “70 year old went past me like I was not even moving.” But if you can figure out how to hit 762 home runs when pitchers are only throwing you curveballs, you can game theory the gears on a bike. Bonds went all in.

Bonds explained his process to Moore: “I fell in love with cycling after my career. I had like six or seven knee surgeries. I had back surgery, and I had three hip surgeries. It’s just that I love sports, but I couldn’t run as much anymore. My character is to wake up in the morning, go to the gym, go home, recover, do it again the next day. That’s my love and my passion, and I’ve found all of that in cycling, because I don’t have to beat my body against the ground, and I can compete against myself.” Bonds used to eat 3,000 calories a day and sit around lifting weights. Both kept him indoors, sitting, safe from the world that viewed him as a monster. It would’ve been easier to keep it that way. He’d been exiled from one community — why try to join another?

But cycling forced him back into the world. He started staging collaborations between his foundation and SoulCycle. He got involved with Zwift, a pioneer in multiplayer online cycling. He began funding (and training with) a women’s Bay Area cycling team called Twenty16. When the pandemic hit, and events were cancelled, Bonds stepped up to fund the Colorado Classic, a four-stage women’s pro road bicycle road race, which supports over one-hundred female riders.

It sounds trite to conclude that Bonds wound up with a more important prize in the end. But it feels true. When Bonds first got into cycling, he was thinking about his father, Bobby Bonds, another ballplayer, who died of complications from a brain tumor and lung cancer at the age of 57. Bonds vowed to take his own health more seriously. He is now 57 years old himself, and Hall of Fame or not, sure seems to be in the best shape of his life.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.