By Mark Asch, Charles Bramesco and Jesse Hassenger

Wes Anderson movies just keep going. Nested narratives open up to reveal films within films, side-quest digressions shot in totally different styles, countless throwaway gags and an encyclopedic density of references, and always, always, a new character to meet, a new face to see.

Anderson’s new film, Asteroid City (out nationwide on Friday), boasts “more stars than there are in heaven,” to quote the old MGM tagline: set around an astronomy conference, it sprawls outwards like the universe itself, full of Junior Stargazers and their postwar parents, astronomers and physicists, schoolchildren, a movie star, several singing cowboys, seemingly the entire military-industrial complex — and that’s just the ones from our world.

Anderson collects things and people. Each of his intricate and detailed fictional worlds, like the elaborately detailed and lovingly laid-out Asteroid City, with its luncheonette and trailer park and meteor impact crater, is like a dollhouse whose dolls come to life, as we all once dreamed they would. Even as Anderson’s recent films have been criticized for their increasing clutter of actors and characters struggling to make an impact, dedicated fans — a category which includes the three authors of this feature — find that they are rewardingly full with indelible bits of performance. Many of these performances spring from the increasingly populous stock company of Anderson regulars, a creative family he’s assembled for himself, to go along with the many onscreen families whose often-fractured dynamics Anderson returns to again and again, as if going a few miles out of the way to drive oh-so-slowly past his childhood home.

As such, ranking Wes Anderson characters feels a lot like ranking your own children — which is to say, it’s something you can imagine a parent doing in a Wes Anderson movie. (You’re picturing Gene Hackman as Royal ranking the Tenenbaum children right now, aren’t you? “#3. Margot: Adopted.” And so on. You’ll have to read on for the complete ranking.) There are many traits that make a Wes Anderson character memorable or quintessential to the filmmaker’s project — intellectual curiosity, reckless rambunctiousness, melancholy that clings like a fog, lovable selfishness, epigrammatic wit, sartorial fastidiousness, facial symmetry — and all of those were taken into consideration in the development of the carefully calibrated scientific formula used in assembly of this list, with the ultimate ranking determined by Jesse when Charles and Mark were out at the bar. (Charles and Mark note: there was a good deal of rejiggering in the cold, sober light of day.) In justifying our choices, we’ve found it enormously rewarding to consider Anderson’s recurring archetypes (many ranked jointly), his favorite actors, and his nagging preoccupations; and to consider how each of these little miniatures reflects back outwards onto the filmography as a whole, little worlds in a grain of sand.

189. Peter Flynn – Luke Wilson, Rushmore

Those are your OR scrubs? OH, ARE THEY?!? –Mark Asch

188-184. The Dead

Chas’s wife in The Royal Tenenbaums; Auggie’s wife in Asteroid City; Max’s mom in Rushmore; the Whitman patriarch in The Darjeeling Limited; Esteban in The Life Aquatic; everyone, eventually

One recurring theme of these blurbs will prove to be family; another will prove to be the lure of the past for Anderson and his characters. Meanwhile, a recurring theme of all the horrible A.I. art generated from a “[X] directed by Wes Anderson” prompt that you may have seen chumming your Twitter feed recently is visual symmetry. In “The Guardians,” a 2001 short story by John Updike, the protagonist, raised by two parents and two grandparents, “felt the four adults as sides of a perfect square, with a diagonal from each corner to a central point. He was that point, protected on all sides, loved from every direction.” We meet many of Anderson’s characters already in mourning, sensing love’s enveloping geometry thrown out of balance, and seeking a return to the symmetry of their once-intact families. Everything is in its right place in every one of Anderson’s shots, but these ghosts remind us that this, too, is a temporary state. –MA

183. Paul Duval — Christoph Waltz, The French Dispatch

Some of Anderson’s tougher critics have found his later-period ensembles, which often seem to be striving to include every actor with whom he has ever enjoyed so much as a passing moment, swollen past the point of effectiveness. We don’t tend to agree. That said, there’s a case to be made that Christoph Waltz is not used to maximum effectiveness as one half of an unsuccessful matchmaking, opposite the distracted journalist Lucinda Krementz. That’s the magic of the biggest rep company in Hollywood, though: Next time, maybe Waltz will get a showcase. Or maybe he’ll play a wordless guy painting sets. You never know! –Jesse Hassenger

182. Future Man — Andrew Wilson, Bottle Rocket

A deleted scene reveals the genesis of the “Future Man” nickname — “He looks like he’s from the future.” “He looks like he was designed by scientists for desert warfare.” — but it’s much funnier in the final cut an unresolved bit of mythology from a filmmaker already so adept at world-building, and much more effective for the lingering implication that tomorrow belongs to people like Bob Mapplethorpe’s meatheaded, sneering, uncreative bully of a brother, the antithesis of everything Anderson stands for. Which just makes Bottle Rocket’s losers all the more beautiful. –MA

181. Chou-fleur — Hippolyte Girardot, The French Dispatch

Hippolyte Girardot has appeared in over 100 films, including ones directed by Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais, Olivier Assayas, Arnaud Desplechin and Hou Hsiao-hsien; he has been nominated for three César awards. When I googled “chou-fleur” to refresh my memory about the role he played for Anderson, all the results were cauliflower recipes from French food blogs — “chou-fleur” being, of course, French for cauliflower. Girardot must really like Wes Anderson movies! –MA

180-169. Various Dogs

Including but not limited to: Buckley (The Royal Tenenbaums), Snoopy (Moonrise Kingdom); and Rex, King, Duke, Boss, Nutmeg, Spots, Jupiter, Oracle, Gondo and Scrap (Isle of Dogs)

Let us be clear: Although Moonrise Kingdom has a more philosophical answer to the question of “was he a good dog?” (“Who’s to say? But he didn’t deserve to die”), these are very good boys. In the pronounced case of Isle of Dogs, an authentic affinity for our canine pals animates the stop-motion around the trash island reigned over by the gang of castaways trying to live up to the alpha-dog supremacy of their names. Every Anderson film builds to one line of leveling earnestness; he reserves the sentimental power of “I’ve had a rough year, Dad” for “What ever happened to man’s best friend?” while invoking the obliteration of the atomic bomb on Japan. Some found his cross-cultural sampling flip or clumsy, but he’s not wrong that the death of a good pooch hits like the end of the world. –JH & CB

168. Professor Watanabe — Akira Ito, Isle of Dogs

As the leader of the Science Party in opposition to the anti-canine fascists mercilessly taking over Megasaki, Professor Ichigo Watanabe (voiced by Tokyo theater fixture Akira Ito) stands as a powerless hero behind his cool-customer sunglasses. He wields far more influence in death, becoming a galvanizing martyr in the wake of his assassination just as he synthesizes a cure for the dog flu. Revolutions need icons, and he posthumously leaves his followers a stirring image to rally around. The authoritarians can poison their enemies, but they can’t poison an idea. –Charles Bramesco

167. Uncle Joe – Henry Winkler, The French Dispatch

Moses Rosenthaler’s reluctant gallerist intones the four unholy words that have echoed around every masterpiece of modern art, and every Wes Anderson film: “I don’t get it.” But Winkler, a kosher ham of the first order, brings a fussy, worried affect to “The Concrete Masterpiece”’s riotous collision of art and commerce, and is a perfect neurotic foil to Anderson’s Looney Tunes–like scenes of antic violence. –MA

166. Assistant Scientist Yoko Ono – Yoko Ono, Isle of Dogs

She may not have been able to keep the Beatles from breaking up, but she was integral in reuniting the people of Megasaki with their missing dogs. –MA

165. The Mechanic — Barbet Schroeder, The Darjeeling Limited

In the emotional centerpiece of The Darjeeling Limited, the movie flashes back to its three lead characters, the Whitman brothers, on a frantic and doomed mission to pick up their late father’s car from a mechanic, so they can drive it to his funeral. The mechanic is played by filmmaker Barbet Schroeder, who made Reversal of Fortune and Single White Female. He is not the focal point of this scene, though he is very believable in the sense that you don’t assume that the mechanic has also directed Single White Female. That’s the character’s function: to serve as a convincing bystander in the brothers’ chaotic grief, which Schroeder imbues with a wispy, mysterious strain of his own mourning. –JH

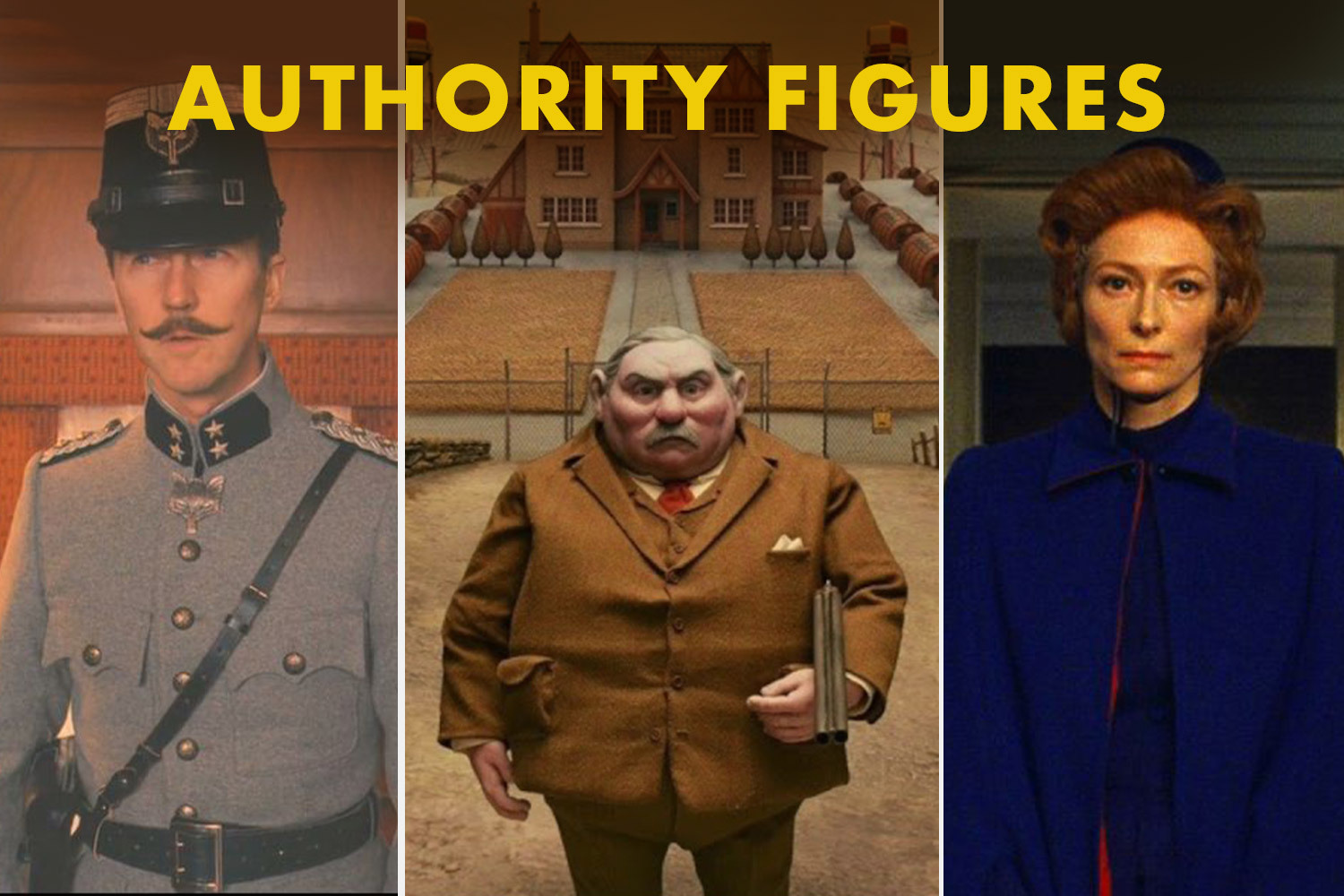

164-153. Various Authority Figures

Mayor Kobayashi (Kunichi Nomura) in Isle of Dogs; Chief Steward (Waris Ahluwalia) in The Darjeeling Limited; Coach Skip (Owen Wilson), as well as Boggis (Robin Hurlstone), Bunce (Hugo Guinness) and Bean (Michael Gambon), from Fantastic Mr. Fox; Oseary Drakoulias (Michael Gambon) in The Life Aquatic; Grif Gibson (Jeffrey Wright) in Asteroid City; Nelson Guggenheim (Brian Cox) in Rushmore; The Commissaire (Mathieu Amalric) in The French Dispatch; Albert Henckels (Edward Norton) in The Grand Budapest Hotel; perhaps most memorably, Social Services (Tilda Swinton) in Moonrise Kingdom.

There’s probably a whole essay to be written about the evolution of authority figures as depicted in Anderson’s films, and the ways in which their officious frustration with the lead characters’ various antics will sometimes give way to acceptance, or at least temporary tolerance. In this way, Anderson doesn’t seem as skeptical of authority as, say, Hal Ashby, nor prone to designating real villains at all, even when they seem to present themselves for just that purpose. (Sometimes, it’s even his characters who are clearly in the wrong, as with nominal authority figures like the Chief Steward in The Darjeeling Limited.) Cox’s Dr. Nelson Guggenheim is very much the crusty old dean of campus comedies, only he has, we gather, shown substantial patience with Max Fischer’s extracurriculars-packed, academically floundering transcript; Social Services seems so-named as a way of poking fun at the kinds of characters that serve as de facto bad guys in stories about orphans, and is ultimately overridden. Anderson’s stop-motion works provide handy exceptions as needed; Mayor Kobayashi is a fascist and the Dahl-created Boggis, Bunce and Bean are grotesqueries of capitalism. He recognizes the existence of evil — Grand Budapest Hotel, with its own band of Nazis, doles out some bloody-handed endings — but seems more interested in recognizing how complicated people cope with it than staring it directly in the face. If this means that villains aren’t his strong suit, and his authority figures are more memorable when issuing comically awkward speeches (see Grif Gibson in Asteroid City), well, who can blame him? –JH

152. Dusty — Seymour Cassel, The Royal Tenenbaums

Royal’s elevator-operator buddy and eventual co-worker at the Lindbergh Palace Hotel is mostly just a chance to grin at seeing Seymour Cassel again; Dusty is a delight, but as far as elevator-operator characters, he’s not quite as memorable as the Coen Brothers’ Buzz, who makes the elevator do what she does in The Hudsucker Proxy. –JH

151. The Chauffeur — Edward Norton, The French Dispatch

The mastermind behind the kidnapping that sets the final segment of The French Dispatch in rollicking motion prefers to operate from behind the scenes, heard on a phone line and glimpsed mostly in passing. We get the best look at him while he waits for the ransom money at his hideout, strumming an acoustic guitar with 90-degree elbows in a pose making subtle reference to Anderson’s favored jazz plucker Django Reinhardt. But could there be another layer of allusion to his choice to introduce Norton with six-string in hand, the same position the actor assumes when first shown in Death to Smoochy? Maybe! Probably not. But we have no way of knowing for sure. Anderson’s got diverse tastes. –CB

150. Mitch-Mitch – Mohamed Belhadjine, The French Dispatch

Anderson is no one’s idea of a radical political filmmaker, but his veneration for 20th century intellectual culture leads where it leads, including, in The French Dispatch, to the Algerian War, courtesy the travails of student radical turned Algerian War draftee turned deserter Mitch-Mitch, a ‘60s Godard pastiche who also later turns black-box playwright in one of Anderson’s most tossed-off depictions of characters metabolizing life into art. –MA

149. Clotilde – Léa Seydoux, The Grand Budapest Hotel

Anderson’s treatment of sexuality has come a long way since Rushmore’s centering of jealous adolescent prudery and The Life Aquatic’s script-girl peekaboo; arguably a turning point came when he dressed Seydoux — at time of shooting on the cusp of a Palme d’Or for her soul-baring performance in the in-the-can Blue Is the Warmest Colour — in a fetching (if geographically dubious) French maid’s uniform as the Grand Budapest’s lissome help. More overt eroticism was to follow, with Seydoux’s considerable aid. –MA

148. The Father — Irrfan Khan, The Darjeeling Limited

Khan’s role as an Indian father mourning the accidental death of his son might be the diciest part of The Darjeeling Limited, which generally pokes fun at the little-boy insensitivities of its white tourists but isn’t quite as surefooted when it comes to crossing their paths with actual little boys (and actual Indian people). But man, does Khan make up a lot of that ground with sheer grace, and man, does everyone miss the hell out of seeing this gone-too-soon performer in movies. –JH

147-138. Musicians and Other Bands of Merry Men

The filmmakers and makeshift sailors of The Life Aquatic, including/especially Seu Jorge; various Jarvis Cocker characters including Tip-Top (The French Dispatch), Petey (Fantastic Mr. Fox) and the singing cowboy he plays in Asteroid City; other singing cowboys (including the one played by Rupert Friend) and various stagehands from Asteroid City

An expertly curated soundtrack has become a trademark of Anderson’s films, as amateur Wes-watchers have made a side sport of incorrectly characterizing what sort of music might turn up in the next one. It’s a fool’s game, because as great as his taste is, Anderson seems increasingly interested in the process of making music and other art as much as the art itself: The collective communities that spring up around a play, a doomed film shoot, a political movement, or even a campfire; he often makes the art itself just rickety or questionable enough to undercut the embarrassing romanticism this might otherwise entail. (It also makes a sly counterpoint to the director’s supposed fastidiousness.) Witness the flight of Petey, the singer voiced by Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker in Fantastic Mr. Fox: He strums a jaunty banjo ditty about the titular character, only to be interrupted by his employer, who admonishes him for bad songwriting. But Jarvis, along with Anderson’s other various bands of stagehands, actors, musicians and interns, will ultimately prevail. The films get made, the songs get sung, the show must go on. –JH

137-133. Narrators/Hosts

Alec Baldwin, The Royal Tenenbaums; Courtney B. Vance, Isle of Dogs; Bob Balaban, Moonrise Kingdom; Bryan Cranston, Asteroid City; Anjelica Huston, The French Dispatch

Whether establishing a playful remove from his storybook worlds, or reorienting our attention as the narrative skips back and forth between multiple layers of fiction, Anderson’s narrators, with their surreally lucid tones and wry verbosity, remind us that above all these stories are authored, and poke good-natured fun at the intellectual traditions that continue to inspire him. Hyperattentive, he seems to have taken equal notice of — and now takes equal pleasure in — the stories that saw and read, and the formal traditions and industrial conditions that shaped them. –MA

132-123. Literati and Media Types

Conrad Earp (Edward Norton), Schubert Green (Adrien Brody) and Saltzburg Kietel (Willem Dafoe) from Asteroid City; The Author from The Grand Budapest Hotel; the entire magazine staff (including Jason Schwartzman, Fisher Stevens and Elisabeth Moss) plus Julien Cadazio (Adrien Brody) and J.K.L. Berenson (Tilda Swinton) from The French Dispatch; chat-show hosts (Larry Pine, Liev Schrieber) in The Royal Tenenbaums and The French Dispatch, respectively; Antonio Monda playing himself in The Life Aquatic

It was so thrilling for me as a teenager to see each character in The Royal Tenenbaums introduced with the cover of a book or magazine they had written or been the subject of — at a time when I hadn’t really made anything yet, but loved the work of people who did, and knew who they were, I understood it as the pinnacle of aspiration: to channel your interests into something permanent and of real cultural import, to cross over from spectator to participant. Anderson’s movies are full of the stuff of culture — the cafés and lecture halls where ideas foment, the typewriters and studios where things are banged or sketched out; the tattered dust jackets and magazine covers in bygone styles; the talk shows where it’s discussed and debated. And it’s full of the people of culture, too, talk-show hosts and fact-checkers and academic celebrities and authors, to populate this ecosystem, to affirm these acts of imagination. –MA

122-121. JJ Kellogg and Roger Cho — Liev Schreiber and Stephen Park, Asteroid City

Some fathers aren’t tragically absent or deeply flawed eccentrics. Sometimes they’re just impatient guys prone to frustrated outbursts and, occasionally, impulsively wielding their son’s death-ray, like JJ Kellogg. And sometimes they’re mostly just supportive of their son’s genius, like Roger Cho. In conclusion, Asteroid City is a land of contrasts. –JH

120. Sandy Borden — Hope Davis, Asteroid City

As mentioned, the parents chaperoning their brainy youngsters into the desert for the Junior Stargazer and Space Cadet Convention err on the side of the supportive, but one mom barely conceals her exasperation once the government-mandated containment unit comes to town. Sandy can’t help speaking her mind, whether in offhandedly mentioning to an actress that no one liked her favorite role or casually snitching on her own daughter for being an obsessive fan. She loves her dear Shelly, but in Anderson’s world of crossed intentions and actions, love takes many counterintuitive forms. –CB

119. Upshur “Maw” Clampette – Lois Smith, The French Dispatch

While French Dispatch publisher Arthur Howitzer ran off to Europe to pursue his aesthetic passions, Maw Clampette brought the continent to the heartland. Equally plainspoken and discerning, the Liberty, Kansas patron of the arts is a composite of several Midwestern collectors, the kinds of local gentry whose bequests filled the walls of museums in places like the Texas of Anderson’s childhood. In a film about Americans abroad, Smith’s salty performance is a tribute to the ones that stayed home. –MA

118. Hank the Mechanic — Matt Dillon, Asteroid City

Matt Dillon doesn’t seem like an obvious choice to drop into Wes Anderson’s world 11 features in, yet here he is, perfectly cast as Hank, another mechanic (who did not direct Single White Female), who lays out a pair of possible automotive maladies early in Asteroid City, only to blithely diagnose the problem as an unknown third thing. Both sides of that interaction are pretty relatable, to be honest. –JH

117. Motel Manager — Steve Carell, Asteroid City

Perhaps destined for trivia by assuming the role Bill Murray was set to play before an ill-timed bout of COVID, Carell nonetheless makes the motel manager of Asteroid City, first seen trying to sell a guest on the advantages of a tent over a proper room, his own oddball creation. Had Murray played the part, we might have too readily believed that he could sell customers on various desert flim-flam. That Carell radiates obsequiousness without ever backing down from, say, selling land parcels via vending machine, makes this running gag of a man even funnier. –JH

116. Clive Badger — Bill Murray, The Fantastic Mr. Fox

Every crook needs a good lawyer, someone to keep an eye on the fine line between illegal and inadvisable, to offer counsel the fast-living thrill-seekers can take or ignore. Master thief Mr. Fox has Clive Badger, Esq., licensed practitioner of the attorney arts and closet demolitions expert, who warns the heist squad against their perilous mission before joining anyway. He’s a ride or die pal, and willing to prove it by putting his own life on the line for his favorite client. –CB

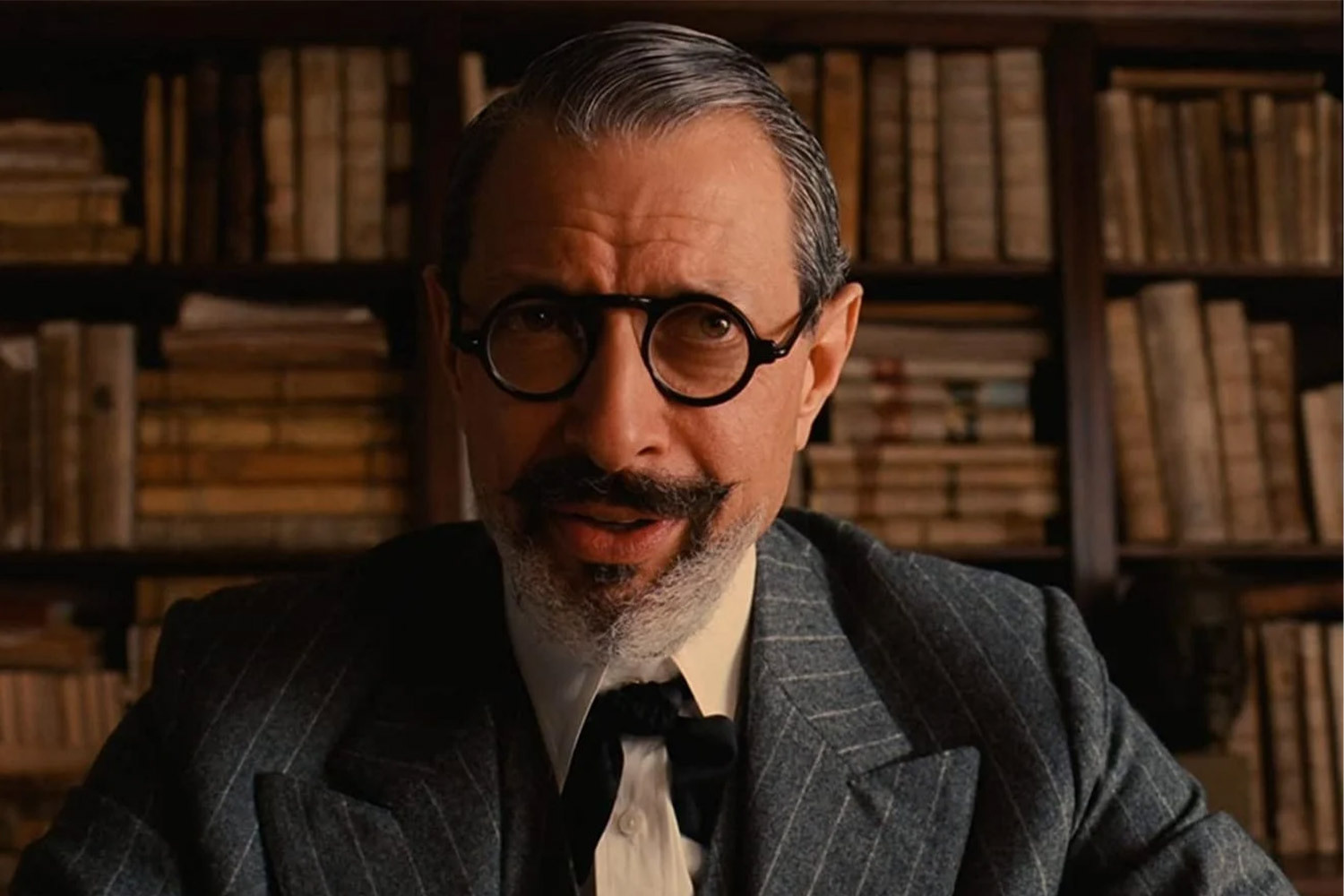

115. Vilmos Kovacs – Jeff Goldblum, The Grand Budapest Hotel

The official legal counsel of the Grand Budapest Hotel just wants to offer sage and reasonable advice, and he gets a bag full of mangled cat remains as his reward. It’s not just; hell, in the moment it’s darkly hilarious. But it portends the larger tragedies coming down the pike for some of the film’s more important characters. –JH

114. Albert the Abacus – Willem Dafoe, The French Dispatch

Perhaps it’s telling that Anderson — an American independent filmmaker who’s seen the Hollywood that took a chance on him as a twentysomething Texan with a single short to his name become ever more agglomerated, risk-averse and leveraged in the time he’s struggled to make his personal films — makes The French Dispatch’s imprisoned criminal mastermind an accountant. (And not just any accountant: An accountant played by an actor with Resting Plague Mask Face.) Perhaps it’s a coincidence! Either way, The French Dispatch was named a “PQ recommendation” by PQ Magazine, which describes itself as “an award-winning magazine for part qualified accountants.” –MA

113. Serge X. — Mathieu Amalric, The Grand Budapest Hotel

This suspicious butler doesn’t have too much to do in the mad scramble to locate a missing painting — he thickens the plot with exposition about a secret second copy of a secret second will before meeting a grisly fate — but the mere presence of the beady-eyed Mathieu Amalric occasions a haunting lit-from-below head-on shot. Anderson loves to sneak in a bit of expressionistic portraiture, and Amalric’s vaguely rodent-like features mount a singular canvas for chiaroscuro shadows. –CB

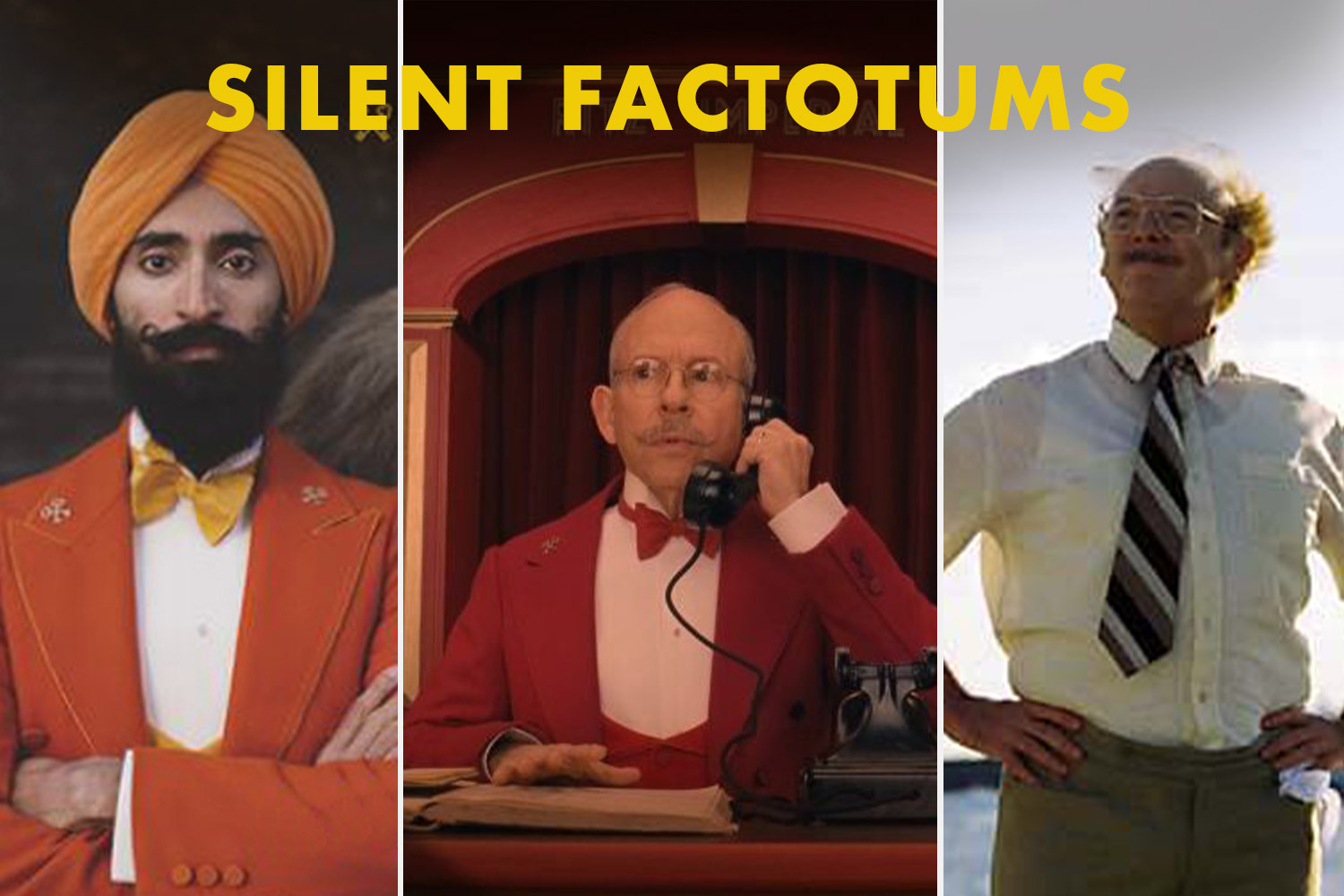

112-97. Silent and Near-Silent Factotums

Bill Udell, Bond Company Stooge (Bud Cort) in The Life Aquatic; M. Chuck (Owen Wilson), M. Martin (Bob Balaban), M. Georges (Wallace Wolodarsky), M. Robin (Fisher Stevens), M. Dino (Waris Ahluwalia), M. Ivan (Bill Murray) and M. Jean (Jason Schwartzman) in The Grand Budapest Hotel; Major Domo (Akira Takayama) in Isle of Dogs; Uncle Nick (Bob Balaban) in The French Dispatch; Tony Revolori, Bob Balaban and Fisher Stevens in Asteroid City; Brendan (Wallace Wolodarsky) in The Darjeeling Limited; Kylie (Wallace Wolodarsky) in Fantastic Mr. Fox; various French Dispatch staffers (including one played by Wallace Wolodarsky)

It’s simple math: when you shorehorn three dozen actors into two hours, giving everyone lines will make things feel crowded, and so some characters must rely only on their appearance, a tacit gesture, and the simple fact of their presence to make an impression. These professional sorts have a businesslike briskness to them, too busy keeping everything in order and accounted for to bother chatting. The patron saint of this stock type is longtime Anderson buddy and early-years Simpsons staffer Wallace Wolodarsky, from a cameo as a referee in Rushmore to a namesake character played by Noah Taylor in The Life Aquatic (James Gray was going to play the role, then bailed when he learned he’d have to hang out in Italy for five months) to a French Dispatch staffer known for collecting a paycheck without actually writing a single word. Anderson’s having a little fun at the expense of the guy he’s glad to have around, regardless of whether or not he’s doing anything. –CB

96-73. Scrappy Kids

Shelly (Sophia Lillis), Ricky (Ethan Josh Lee), Clifford (Aristou Meehan), and the three witchy little sisters from Asteroid City; Ari (Grant Rosenmeyer) and Uzi (Jonah Meyerson) from The Royal Tenenbaums; Atari (Koyu Rankin) and Tracy (Greta Gerwig) from Isle of Dogs; Dirk Calloway (Mason Gamble) and Magnus Buchan (Stephen McCole) from Rushmore; Kristofferson Silverfox (Eric Chase Anderson) from Fantastic Mr. Fox; the various scouts of Moonrise Kingdom; the grumpy revolutionary teenagers of The French Dispatch; etc.

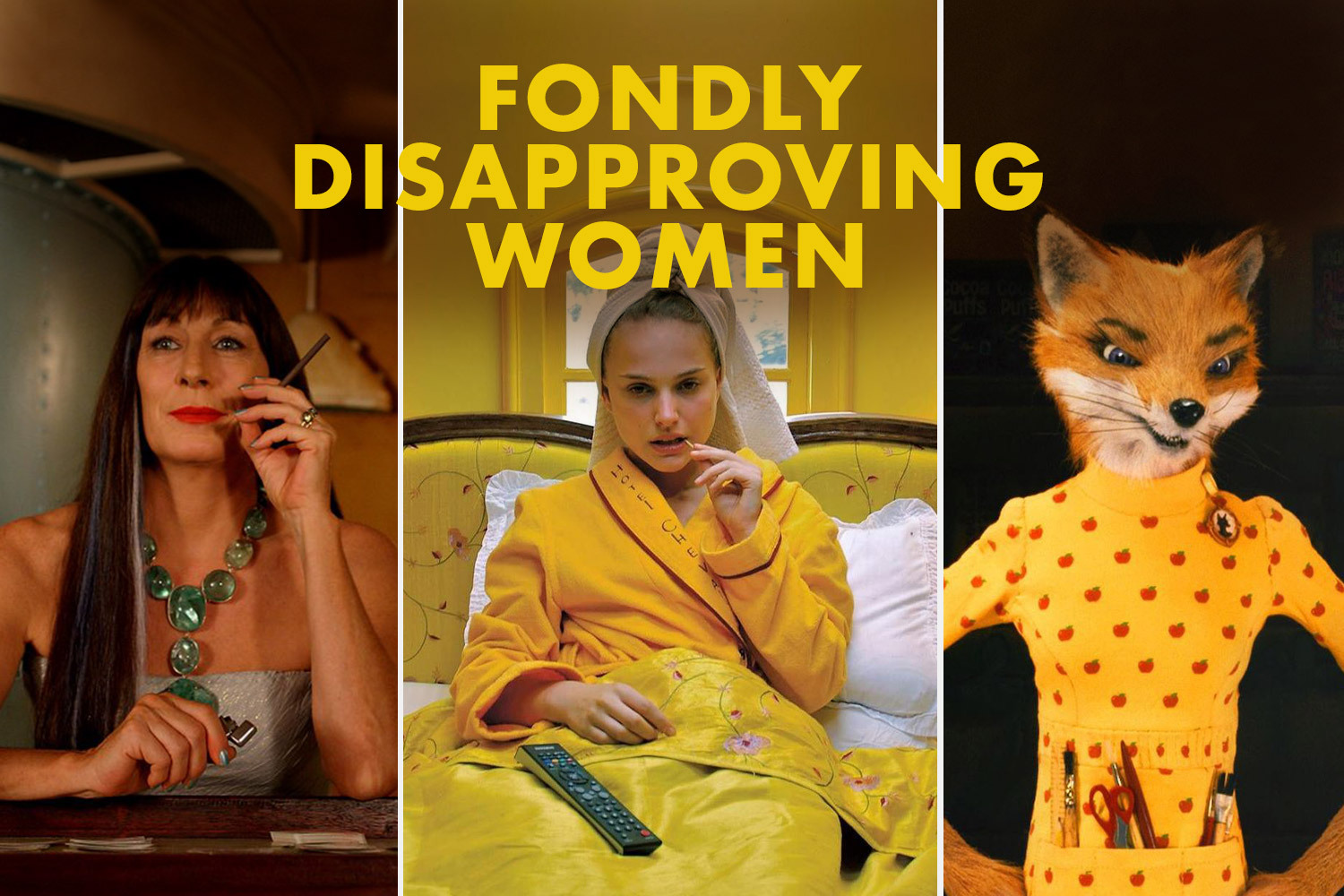

The Wes Anderson childhood is not one-size-fits-all, even in minor supporting roles; he recognizes that kids can be sensitive li’l geniuses, as in The Royal Tenenbaums; sweetly mischievous, in that very same movie; collectively cruel or brave, as in Moonrise Kingdom; full-on bullying, like Magnus in Rushmore; or just plain weird, as in the Macbeth-like trio of little sisters periodically invoking dark magic during Asteroid City. What ties these supporting kids together like background plays in a Peanuts dance scene is their scrappy resilience, almost always giving way to some kind of acceptance akin to Magnus’s confession to Max: “I always wanted to be in one of your fuckin’ plays.” Anderson’s movies are full of death, repeatedly breaking a key dictum of American cinema by killing off innocent dogs, but they tend to ultimately leave the kids alone and let them survive, even or especially if it means growing into childlike adults. (Is survival not enough? Must we also become boring?) The Darjeeling Limited offers the exception that proves the rule, where the death of a child, even a stranger, feels so wrong that it disorients everyone in the act’s terrible orbit (and, metatextually, maybe feels like a bit of a cheat in the movie itself). Though his movies lack think-of-the-children sanctimony, it’s also hard to think of an American filmmaker so keyed into the roughness and weird glories of kidhood. –JH

72-63. Ambivalent or Fondly Disapproving Women

Eleanor (Anjelica Huston) in The Life Aquatic; Patricia (Anjelica Huston) in The Darjeeling Limited; Rhett (Natalie Portman) in The Darjeeling Limited and Hotel Chevalier; Rita (Amara Karan) in The Darjeeling Limited; Agatha (Saoirse Ronan) in The Grand Budapest Hotel; Mrs. Calloway (Connie Nielsen) in Rushmore; Polly Green (Hong Chau) in Asteroid City; Simone (Lea Seydoux) and Junkie/Showgirl (Saoirse Ronan) in The French Dispatch; Inez (Lumi Cavazos) in Bottle Rocket

Anderson often prefers the suggestion of things to things themselves: he crafts visions of foreign nations based on postcards and pop culture, refers to life-shaping events with passing scraps of dialogue, and collapses decades of decline into a single brutal cut. This can get hairy when writing women, their complexities hidden away in elisions meant to reflect the inadequate understanding of the foolhardy men in their lives. While stunted male protagonists go off to pursue the quixotic missions they’re convinced will make them whole, the women who know better offer a piquant mix of pity, annoyance and begrudging warmth. They bear the burden of maturity, a thankless duty assigned out of esteem, bestowing some (Simone, Polly, Rhett) with suggestive windows into compacted depths of the heart and leaving others (Agatha, Inez, various Angelias Huston) frown-smiling from the sidelines. –CB

62. Dr. Hickenlooper — Tilda Swinton, Asteroid City

Swinton usually goes big, heavily made-up and swoopy for her Wes characters, among her most stylized co-creations this side of Snowpiercer. But she’s most affecting as Dr. Hickenlooper, an earnest, probing and at least partially clueless scientist in the midst of an alien encounter in Asteroid City — so transparently a grown version of the socially awkward nerds she takes under her wing. –JH

61. The Actress — Margot Robbie, Asteroid City

What would possess Margot Robbie to say yes to a role with a minute or two of screen time, no name and enough lines to count on two hands? Her absence places such a heavy weight on each tier of the nested narrative that her long-awaited appearance requires a matching gravitas only a star of her stature could supply. The character hovers over the various levels of metatext like a specter, eventually revealed as the dramatic fulcrum supporting a tangled thicket of missed connections from the center. She’s the one that got away, as only she could be. –CB

60. Madame D. – Tilda Swinton, The Grand Budapest Hotel

The dowager owner of the GBH takes her name from the title character of Max Ophüls’s flawless 1953 melodrama The Earrings of Madame de…, and although Swinton is game (when is she ever not?) for some impossibly regal old-age makeup, one notes that Ophüls’s original Madame de…, the grand dame of French cinema Danielle Darrieux, who died in 2017 aged 100, was still alive at the time, and had appeared onscreen as recently as 2011. You know Wes asked. –MA

59-58. Mr. & Mrs. Bishop — Bill Murray and Frances McDormand, Moonrise Kingdom

Okay, yes, the pair of lawyers communicating via bullhorn and leaving books about what to do with your mentally disturbed daughter in plain sight may not win any medals for Parents of the Year. But like all of Anderson’s misshapen adults, they’ve got their own stuff going on; a man who responds to stress by clutching a bottle of hooch and venturing into the woods with a hatchet should probably look inward before getting involved with his kid’s mental health. The pair bicker like children, setting the example that Sam and Suzy swear to overwrite with their two-person commune, a needed Eden never to be spoiled by the hostile questioning and low-simmering animosity she’s learned to associate with marriage. –CB

57. June Douglas — Maya Hawke, Asteroid City

As a good Christian teacher shepherding her roll-called flock of rapscallions through an event challenging the existence of God, Miss Douglas tries to keep it together and continue with her lesson on the solar system while the laws of physics crumble around her. It comes as a miniature treat, then, when she undoes a couple schoolmarm buttons for a carefree hoedown with the cowpoke what’s been romancin’ her real polite-like. It’s the end of the world as she knows it, and she figures there’s no harm in letting herself feel fine. –CB

56. Ned Plimpton — Owen Wilson, The Life Aquatic

He may be named after George Plimpton, the intrepid “participatory journalism” progenitor in line with The Life Aquatic‘s robust hunger for exploration, but Ned boards the Belafonte as a meek fan half-duped into financing a wild goose chase. He takes a more explicitly Oedipal route than most of Anderson’s arrested development cases to a long-delayed manhood, roused to action by sexual competition with the non-dad he never knew over a woman already pregnant with someone else’s child. In a film preoccupied with several different strains of male impotence, he preserves his newfound dignity in the only way Anderson’s universe of elusive contentment will permit. –CB

55. Lt. Nescaffier — Stephen Park, The French Dispatch

As the preeminent authority in the discipline of police cuisine, the immigrant lieutenant (his name a portmanteau of French-beloved coffee brand Nescafé and haute cuisine codifier Auguste Escoffier) made himself indispensable in order to claim his piece of a country that often shunned him as a foreigner, a placelessness that cues up the film’s most disarming moment of shared empathy before a noble sacrifice. More schooled in the use of a paring knife than pistol, he gets a special exemption from the whole ACAB thing. –CB

54. Rat — Willem Dafoe, Fantastic Mr. Fox

He’s there in the original Dahl book, though more of an angry, self-pitying drunkard than stylish psychotic, perfectly matched to Willem Dafoe’s Green Goblin menace. And Dahl certainly doesn’t give him a memorable death scene, where he laps up puddle water, convinced that it’s the finest alcoholic cider in the land, or this poetically pitiless eulogy: “Redemption? Sure. But in the end, he’s just another dead rat in a garbage pail behind a Chinese restaurant.” (Chased by an addendum: “He went bananas.”) –JH

53. Dinah Campbell — Grace Edwards, Asteroid City

Conceived in part as a female opposite for our boy Woodrow — she articulates the contents of his soul when she claims to feel more at home outside the Earth’s atmosphere — this crush object could’ve been a flat projection of desire. But Edwards brings a deeper wisdom and ineffability to her brief time onscreen, credibly embodying the untold depths a lovelorn boy might imagine in the cute girl at camp. –CB

52. Henry Sherman – Danny Glover, The Royal Tenenbaums

The author of Accounting for Everything is an outsider in the rarified air of the Tenenbaums, and in the Anderson filmography in general, for reasons that go beyond skin deep (though Henry’s Blackness, the subject of multiple still-shocking Royal quips, is surely Anderson’s preemptive response to critiques of his insularity). Played by Glover with immaculate gentleness and rectitude, Henry is polite, self-conscious and conscientious in a world of brash solipsists; he’s one of the only men in the entire filmography who acts his age. –MA

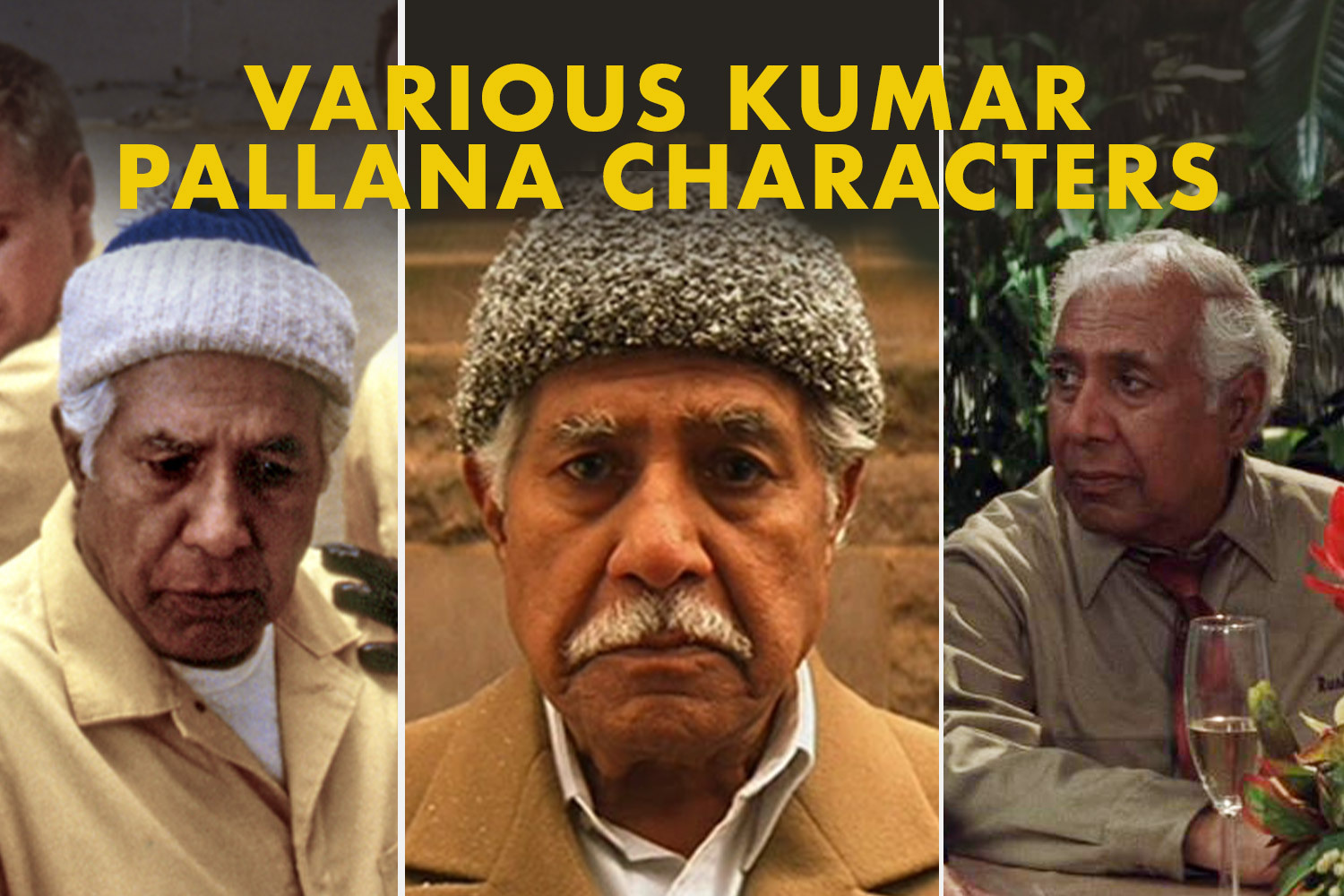

51-48. Various Kumar Pallana Characters

Pagoda in The Royal Tenenbaums; Mr. Littlejeans in Rushmore; Kumar in Bottle Rocket; an old man on the train in The Darjeeling Limited

Are we heading into #problematic territory? It’s certainly true that there aren’t a wealth of major nonwhite characters in the early films of Wes Anderson, and that he uses Indian-American performer Kumar Pallana largely for laughs. But Anderson, who met the former vaudevillian (early film and TV roles: uncredited soldier in Viva Zapata! and spinning plates on The Mickey Mouse Club) at a Dallas cafe owned by Pallana’s son, held obvious affection for the man, who died at the age of 94 in 2013 — and Pallana goes after those laughs with his understated delivery, whether cavalierly explaining that he can’t crack a safe in Bottle Rocket (“I lost my touch, man”) or matter-of-factly stabbing his boss Royal in The Royal Tenenbaums. –JH

47. Cousin Ben — Jason Schwartzman, Moonrise Kingdom

Jason Schwartzman can serve as the soul of Anderson’s movies and the director’s frequent stand-in. Or, in between those leading gigs, he can just be kind of a prick, insisting on keeping a can full of nickels as a fee for performing an extralegal marriage for a couple of barely-adolescent kids. –JH

46. Abe Henry – James Caan, Bottle Rocket

The landscape architect and criminal mastermind in the middle phase of Dignan’s 75-year-plan is played by Sonny Corleone himself, with bluster and gusto, but it turns out that life as a landscaper-cum-accessory to armed robbery isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Anderson’s first feature is also his first film (of many) with a disappointing father figure; made when the director was entirely unknown, it’s also his first film (of many) to be graced by a legendary actor playing a distillation of his famous persona, suggesting that the overarching adored patriarch in the Anderson filmography is cinema itself. –MA

45. Alistair Hennessey – Jeff Goldblum, The Life Aquatic

Suave, successful, condescending, and, by his own admission, part gay, Steve Zissou’s professional nemesis stands apart from the Belafonte’s atmosphere of scrappy camaraderie — though by the end of the film he, too, is reconciled and reabsorbed into the core group. As Steve reminds him: “Supposedly, everyone is” — part gay, that is, but also, perhaps, welcomed into Anderson’s ensemble, to which Goldblum has continued to contribute off-kilter line readings since. –MA

44. Chief — Bryan Cranston, Isle of Dogs

As cataloged earlier, Anderson has a whole kennel’s worth of very good boys in his filmography; Chief stands out because he transposes the defensive woundedness of other Anderson characters into the body of a canine, so often depicted as particularly eager to please. Chief grapples with his willingness to attach himself to a new human, before relenting in the face of child bravery; he struggles, so that other dogs may give themselves over to a flawed, sometimes cruel humanity with abandon. –JH

43. Woodrow Steenbeck — Jake Ryan, Asteroid City

Anderson has never made a movie as naturalistic as Richard Linklater’s Boyhood, but occasionally you catch a glimpse of a similar effect when he brings back players from his various kid ensembles (see above) to promote them into bigger parts. Case in point: Jake Ryan, the little brother who growls an inquiry about his missing record player in Moonrise Kingdom, is now Woodrow Steenbeck, a nerdy teenager who has recently lost his mother and is perched between childhood and the adult world, with all the heartache (an emotionally constipated dad), wonder (a new girlfriend?!) and mystery (do I even belong here on Earth?) that may entail. –JH

42. Jane Winslett-Richardson — Cate Blanchett, The Life Aquatic

A forgotten heroine of the Anderson oeuvre, possibly because Blanchett never re-upped for more (did Tilda replace her?), or possibly because she stands her ground and eventually, presumably departs the weird little world she visits when writing a profile of Steve Zissou. Either way, the toughness Blanchett brings to the part becomes oddly touching. –JH

41. Bert Fischer — Seymour Cassel, Rushmore

This list is originally running around Father’s Day, and is there a flat-out better dad (as opposed to an unexpected father figure) in Anderson’s filmography than humble, soft-spoken barber Bert Fischer? He may not be a temperamental match for his son Max, but whatever of Max’s wildest plans seem beyond Bert’s understanding remain unspoken. He’s not a complicated guy, which might make him one of Anderson’s more low-key fantasies; would that more kids would have the luxury of saying that about their dads. –JH

40. Etheline Tenenbaum – Anjelica Huston, The Royal Tenenbaums

Although we earlier devoted a whole umbrella category to “fondly disapproving women,” both the fondest and the most disapproving is Etheline Tenenbaum, mother of geniuses, ex-wife of Royal (played by Huston, herself the precocious scion of an accomplished, larger-than-life family — in old photos from her modeling days she looks not unlike a dark-haired, or rather unbleached Margot). Etheline’s delicate yet acid-tipped inflections convey her character’s singular mix of dotty indulgence, impossibly high standards and sheer exhaustion at the constant antics of her prodigal brood; so many of Anderson’s characters come off like — or actually are — energetic, hyperarticulate, emotionally unsophisticated children, and it’s through Etheline’s eyes that we see them most clearly in their totality. –MA

39. Dudley — Stephen Lea Sheppard, The Royal Tenenbaums

A subject of researcher Raleigh St. Clair, Dudley is a teenager suffering from a “rare disorder combining symptoms of amnesia, dyslexia and color-blindness, with a highly acute sense of hearing.” (He’s also quite astute at pointing out dents in cabs.) As played by the inimitable Stephen Lea Sheppard (geek guru Harris on Freaks & Geeks), he’s a glorious reminder of just how sanitized and overscrubbed so many Hollywood-borne teenage nerds and outsiders really are. I desperately want a Breakfast Club redo with Dudley types in at least two of the main roles. –JH

38. J.G. Jopling — Willem Dafoe, The Grand Budapest Hotel

Shadow of the Vampire first noted the resemblance between Willem Dafoe and Nosferatu‘s Count Orlok in the year 2000, a likeness deployed by Anderson to delightfully unsettling effect for the brass-knuckled attack dog unleashed by the perfidious Dmitri. Hot on our heroes’ trail and leaving a trail of corpses behind him, he verges on the nonhuman in his tireless drive to kill, a vampiric bloodlust accented by close-ups complete with German Expressionist lighting. Dafoe did his part just by having one of those faces. –CB

37. Margaret Yang — Sara Tanaka, Rushmore

What about the prodigious kids who aren’t afforded prep school, elaborate field trips or books extolling their genius? They can look up to Margaret Yang, the public-school girl who reaches out to Max Fischer after his expulsion from Rushmore Academy. He rebuffs her at first, and she manages to maintain her empathy without seeming like a pushover; her last line in the movie is telling Bill Murray to get his own dance partner. –JH

36. Lucinda Krementz – Frances McDormand, The French Dispatch

Many of Anderson’s characters are published authors, but Krementz—based on New Yorker Paris correspondent Mavis Gallant, and named for the photographer Jill Krementz, Kurt Vonnegut’s widow—may be the best writer. As heard in voiceover, her prose channels a long New Yorker tradition of writers, mostly women, who levy devastating intellectual judgments and recount roiling emotional subjectivity with the same brisk, insinuating lucidity. –MA

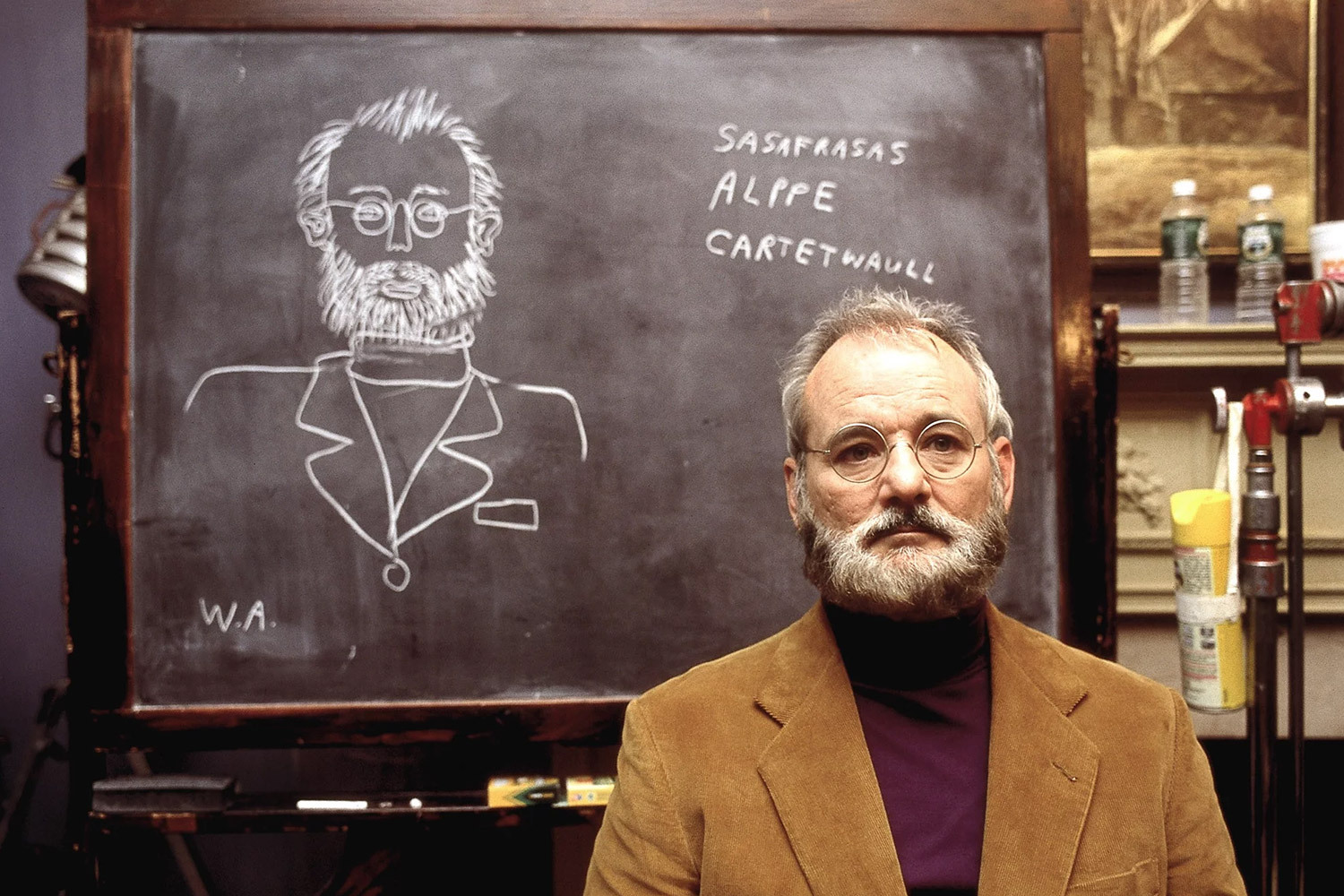

35. Raleigh St. Clair — Bill Murray, The Royal Tenenbaums

“A neurologist who can’t see past the protective walls his wife has built up around her mind” sounds like an ironic invention one notch too clever for its own good, and yet Murray plays the cuckold’s combination of hyperintelligence and interpersonal obliviousness with a moving hint of concession. He’s accepted that he’s a supporting figure passing through the life of Margot, an elaborate drama in which she always sees herself as the main character. He knows he can’t fully know her, and that that’s just how she likes it. -CB

34. Bob Mapplethorpe — Robert Musgrave, Bottle Rocket

Wes Anderson tends to stick by his roster of actors, but Robert Musgrave — discovered in a Texan bar where his buddies Luke and Owen Wilson used to hang out — promptly returned to the obscurity from whence he came after stealing scenes as the wild card in Bottle Rocket‘s crack team of amateur criminals. He set the template for the oddballs rounding out the many taskforces in Anderson’s oeuvre, and then true to the spirit of fast-living crook Bob Mapplethorpe, decided he’d rather spend the rest of his life taking it easy. –CB

33. Ash Fox — Jason Schwartzman, Fantastic Mr. Fox

Perhaps aware of the leeway afforded to an adorable little stop-motion fox, Ash Fox is a surly teenage crank, grumbling about his underappreciated athletic prowess and plotting revenge against his mild-mannered (but more athletic) cousin. It’s a change of pace in a world where even the most cocksure characters tend not to be jocks, aspiring or otherwise, and cloak teenage rebellion in fastidious fashions. That he’s a named character at all feels like an act of rebellion unto itself; in the Roald Dahl novel, Mr. Fox has four essentially anonymous children. In the movie, Ash demonstrates that you don’t need a litter of siblings to feel “little,” overlooked and pissed off about it. –JH

32. Stanley Zak – Tom Hanks, Asteroid City

Asteroid City is Anderson’s most Americana-steeped movie, and so it’s naturally America’s Dad, WWII history buff Tom Hanks, who brings a fundamental decency and reassurance to the role of a crusty, benevolent grandpa arrived at an interstate motel wracked by grief and steeped in Atomic Age paranoia. Adlai Stevenson never stood a chance. –MA

31-30. Zeffirelli and Juliette — Timothée Chalamet and Lyna Khoudri, The French Dispatch

Ah, those crazy kids. The hot young revolutionaries of May ’68 find worthy avatars in preternaturally pretty leftists Chalamet and Khoudri, their disaffection and political principles tempered by the blinkered vantage of adolescent idealism. They’re ideologically pure to a fault, though Anderson (and the embedded journalist who sleeps her way into her own story) have no interest in chiding them, instead guiding them to a reminder that we only make war so that we can get back to making love. –CB

29. Jack Whitman — Jason Schwartzman, The Darjeeling Limited

The bridge-torching narcissist of Listen Up Philip may not even be the most Difficult Male Novelist Schwartzman has played: Jack, with his cruel quips and callous treatment of new and old love interests alike, is a perfect example of the trope and Anderson’s attempt, post-Tenenbaums, to push his inquiry into the psychological effects of formative trauma into darker territory. Because it’s Schwartzman, and because we remember him young, it’s sad and scabrous at once. –MA

28. Dmitri — Adrien Brody, The Grand Budapest Hotel

A foulmouthed homophobe, a greedy little weasel, a violent brute without the mettle to get his own hands dirty, a Nazi collaborator — Dmitri provides no shortage of causes for contempt, but Anderson identifies him as the true villain of this Alpine adventure with his dour all-black costuming. In a world where style, luxury and manners act as currency, he’s utterly bankrupt. –CB

27. Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro and Tony Revolori), The French Dispatch

Though Benicio Del Toro plays murderous imprisoned artist Moses Rosenthaler for most of the French Dispatch segment “The Concrete Masterpiece,” he’s embodied in early scenes by Tony Revolori, playing the character as a younger man. As his time in prison stretches out in front of him, Anderson makes one of his simplest presentational moves yet: He simply has Del Toro walk into the frame and gently tag Revolori out, assuming the role of an older Moses in front of our eyes. No matter the violence that follows, Moses will never shake that poignancy. –JH

26. Klaus Daimler — Willem Dafoe, The Life Aquatic

Late in The Life Aquatic, adventurer and filmmaker Steve Zissou divides up his team for a “lightning-strike rescue op,” and doesn’t place his right-hand man Klaus on the team he’s leading. “Thanks a lot for not choosing me,” Klaus spits, an ocean of hurt crossing his face as he laments being placed on the B-squad. On one hand, if someone as intimidatingly intense as Dafoe can be made to feel this way, what hope do any of us have? On the other, if Dafoe’s distinctive glower can be reduced to a little-boy scowl, maybe we can give ourselves a break on our own childish instincts that lurk beneath our grown-up skin. And may we all be comforted with the combination of coddling and honesty contained in Steve’s response: “You may be B-squad, but you’re the B-squad leader.” –JH

25. Scout Master Ward — Edward Norton, Moonrise Kingdom

WesWorld is overrun with grown-up nerds holding fast to their lifelong preoccupations, and it’s not as if Scout Master Ward has a dayjob far removed from his: He teaches eighth grade math, a seemingly good gig for an upstanding guy sporting a natural rapport with kids. But at one point in Moonrise Kingdom, Ward has a revelation: He is Scout Master of Troop 55, “math teacher on the side.” Whatever this doesn’t sum up about his character (and it gets at most of it) is provided by the presence of Edward Norton, somehow matching his earnest best years past his most youthful go-getter roles. –JH

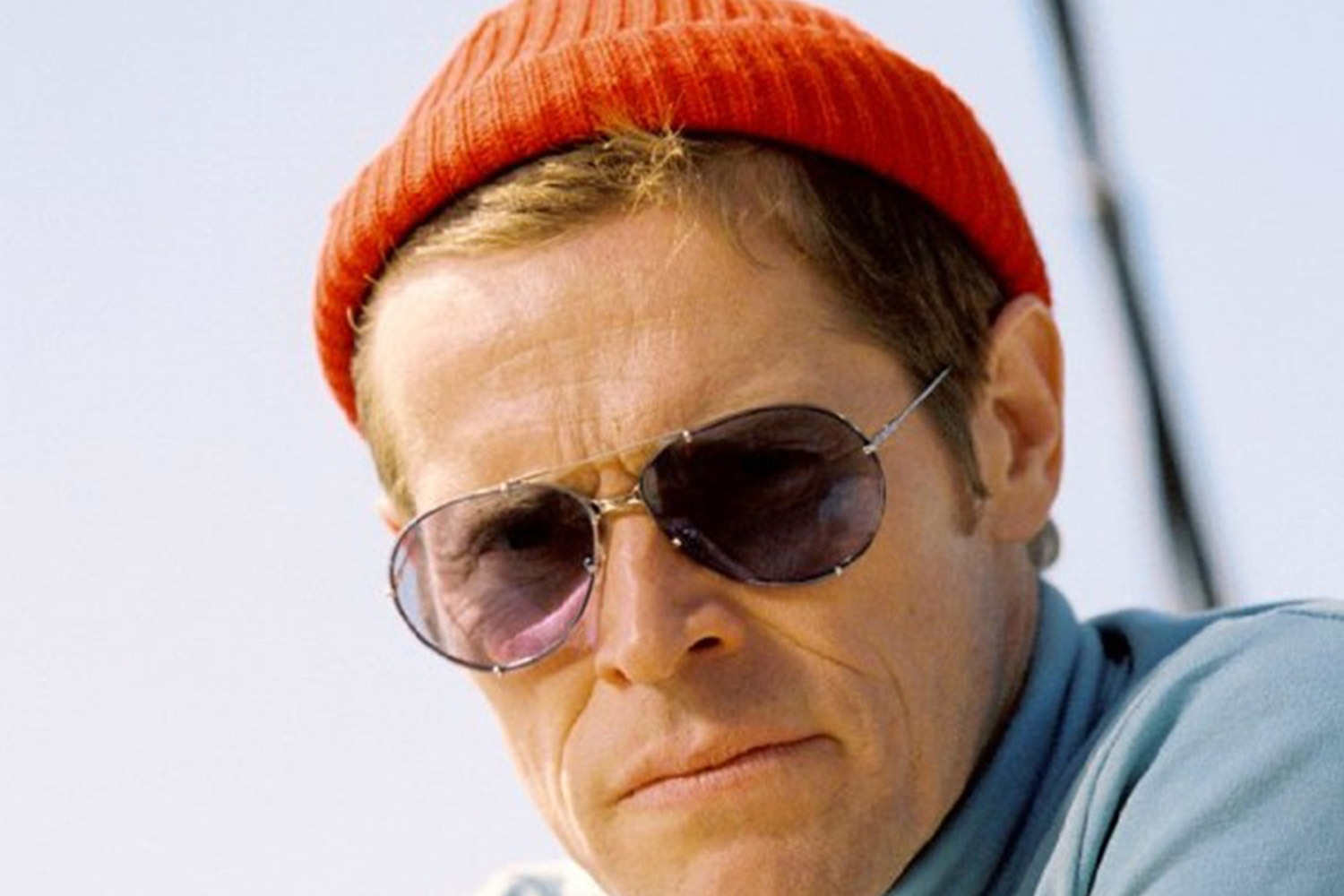

24. Peter Whitman — Adrien Brody, The Darjeeling Limited

The other two brothers at the center of The Darjeeling Limited have recognizable Wes Anderson affectations and accouterments: Francis has his hyper-planned and carefully laminated itineraries delivered via beleaguered attaché, while Jack has his literary career and heartbreak playlists. Peter isn’t unburdened by any of this, but he keeps his curation closer to his chest — or face, as he persists in wearing his dead dad’s prescription sunglasses even as they give him a headache. So many Anderson characters treat their father figures with some remove or resistance; whatever of that existed in Peter remains hidden by his grief. Sad-eyed Brody is hilarious in other Anderson movies, but never more affecting than he is here. –JH

23. Eli Cash – Owen Wilson, The Royal Tenenbaums

Anderson’s most quotable character — “Maybe he didn’t?” is part of the American vernacular, and when Cormac McCarthy died earlier this month, the first phrase that sprung to many minds was “friscalating dusklight.” In his fringed leather jacket and in his clandestine affair with the girl next door, Eli is the ultimate pretender, an urban-cowboy poser who “always wanted to be a Tenenbaum” — it’s he who delivers Anderson’s career-defining statement about the desire to find the place where one belongs, and the people one belongs among. (And it’s difficult to imagine Anderson entrusting the line to any other actor.) –MA

22. Anthony Adams – Luke Wilson, Bottle Rocket

He’s really complicated, but he tries not to be — Anderson’s first protagonist ends up drawn into a life of crime out of loyalty to a childhood friend. Nostalgia is always a potent animating force in Anderson’s films, and Anthony (played by the younger brother of a close friend of Anderson’s youth; both are his longest-running collaborators) embodies the ambivalence with which Anderson characters often approach their own maturation, and the openness to adventure, however ill-advised, that continues to spark wonder in his narratives. –MA

21. Herbsaint Sazerac — Owen Wilson, The French Dispatch

Granted, this is less a character than a vehicle for a glorious barrage of gags, from sight to verbal to slapstick, at the front of The French Dispatch; that he’s also riding a vehicle, taking viewers/readers on a bike tour of Ennui-sur-Blasé, is a perfect hat-on-a-hat Andersonian construction. (In other movies, a hat on a hat is bad. In Anderson’s, you’re like, “Wow, cool, look at those two hats!”) Would-be hardcores have lamented that Wilson no longer co-writes Anderson’s screenplays, but doesn’t having Owen Wilson say your lines in his distinctive Texan surf-drawl constitute a sort of an automatic co-authorship? –JH

20. Rosemary Cross – Olivia Williams, Rushmore

Few men in history are easier to picture than Wes Anderson as a high schooler with a crush on one of his teachers. Ostentatiously bookish, he seems in his films to be eager — to please, to be singled out for his specialness, to be lightly scolded when he takes it too far, to thrive under a reluctantly admiring gaze. But you can’t go to Rushmore for the rest of your life — as Miss Cross makes it clear to Max Fischer through the sharpness of her disapproval and the complexity of her desires. Experience is the greatest teacher, and she’s experience personified. –MA

19. Zero Moustafa — Tony Revolori and F. Murray Abraham, The Grand Budapest Hotel

We’re acquainted first with an aged Zero, the handsome yet weathered facade of F. Murray Abraham’s sturdy visage cracking just enough to suggest a lifetime of accumulated melancholy. He then graciously allows us to peer inside, and shares the whole story: from refugee to proprietor of a palace in decline, all seen through the tea-saucer eyes of remarkable find Tony Revolori. Though his post as lobby boy puts him in a necessarily subservient role, his bravery, hypercompetence, and quick thinking win the day along with the respect of his obligatory paternal mentor. The Grand Budapest Hotel marked the beginning of Anderson’s current political period in 2014, around the same time cheap shots about his casts’ whiteness peaked among the commentariat; the fully-formed, funny yet forlorn Zero was the first in a series of compassionate rebuttals. –CB

18. Arthur Howitzer Jr. — Bill Murray, The French Dispatch

The bond between writer and editor transcends misplaced commas and rearranged sentences, deepening into a sacred trust that Anderson channels into his career-long preoccupation with compromised father figures via Arthur Howitzer Jr., founder and EIC of The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun. Played by Rushmore‘s surrogate bad dad Bill Murray, he mostly hangs over the article-segments that comprise this Gallic anthology, the scant flashbacks in which he stands by “his people” a eulogy for a vanishing model of publishing and the standards that went with it. He looked after and out for everyone, his absence in monochrome underscoring the current of loss that runs through the entire Anderson canon. And on top of all that, he coined an immortal editorial axiom in “Try to make it sound like you wrote it that way on purpose.” –CB

17. Chas Tenenbaum — Ben Stiller, The Royal Tenenbaums

Chas Tenenbaum is right in Ben Stiller’s wheelhouse: Insecure beneath his surface intelligence, quick to anger, frequently irritated by an Owen Wilson type. Yet The Royal Tenenbaums crystallizes something that’s not quite there in Stiller’s other performances, no matter how good some of them are: The neurotic fear of uncontrollable events, and how they increase exponentially in parenthood. Chas doesn’t want to forgive Royal his many parental misdeeds because he truly believes forgiving your parents shouldn’t be necessary — presumably in turn because he fears needing that forgiveness himself down the line, especially now that he’s a widowed single parent. The comic’s neediness that comes through in other Stiller roles turns rawer in perhaps the most heartrending moment of Anderson’s filmography: Moved by his father’s attention to Chas’s young sons, and shaken up by a near tragedy, his voice breaks as he admits: “I’ve had a rough year, Dad.” –JH

16. Captain Sharp – Bruce Willis, Moonrise Kingdom

The young-love story in Moonrise Kingdom is clouded by the promise of adult disappointment; runaways Sam and Suzy are pursued by a roster of grown-ups whose aim is to pull them back into the very world that’s made them all so sad, none more so than New Penzance’s only policeman, who’s weary to the bone and in love with a married woman who mostly tolerates him as a change of pace. It’s a sign of hope when Captain Sharp finds a way to be something other than a figure of deadening authority to Sam and Suzy — and a funny joke when he turns hero during a hair-raising rescue on the roof of a tall building, like a very lo-fi Die Hard. –MA

15. Richie Tenenbaum – Luke Wilson, The Royal Tenenbaums

Poor sensitive jock Richie (in the Joy of Sex–era Björn Borg clothes that constitute one of Anderson’s formative magpie-like pilferings from the breadth of 20th century style and culture), called back to the womblike tent where he used to camp with his sister. Somehow his arrested development is even more poignant for his gifts being physical and instinctive, rather than intellectual. Richie’s suicide attempt, set to Elliott Smith’s “Needle in the Hay,” also laid down a marker for the real stakes behind Anderson’s brand of attractive, diffident mopery, as well as the unerringly curated pop lyricism with which he builds such moments. –MA

14. Midge Campbell — Scarlett Johansson, Asteroid City

A movie’s notion of a movie star can’t fake the light and heat that stars radiate; when a screen idol steps off the train in the remote desert town hosting the convention where her egghead daughter is to receive a commendation, the woman we see needs to be genuinely luminous, radiant, beckoning with the hint of unknowable mystery prized in the Hollywood glitterati. So yeah, it helps if Scarlett Johansson says yes. As a midcentury Actors Studio–styled glamourpuss, she can barely keep her own tragic sense of stardom at bay, resigned to ending life as a Tinseltown cliché in a bathtub surrounded by pill bottles. Behind the camera-ready poker face, behind the many layers of performance draped over one another by the byzantine structure of the film, a small, steady, clear note of sadness rings out. –CB

13. Francis Whitman — Owen Wilson, The Darjeeling Limited

One month prior to The Darjeeling Limited’s world premiere at the Venice Film Festival in 2007, Owen Wilson attempted suicide in a highly publicized episode that turned him off from interviews for a good chunk of his career. The awareness of his real-world struggles with depression informs and enriches his performance as a man at a similar rock bottom, staving off his ideation by dragging his brothers into a contrived “spiritual journey” through India that he’s planned down to the minute. He leads their search for the same inner enlightenment as innumerable white tourists pouring into the hub of Hinduism, but in Francis’s damaged face, we can see the deep-seated, terribly true interior pain behind the ethnocentrism that slowly, gently thaws into humility. –CB

12. Augie Steenbeck — Jason Schwartzman, Asteroid City

Speaking of that Boyhood phenomenon: Early Anderson fans will surely turn to some bespoke form of neatly piled dust upon the realization that former troubled teenager Jason Schwartzman has now aged into playing the fumbling-dad role, as Augie Steenbeck, a father of four who’s so unprepared for life without his recently deceased wife that he waits weeks to break the news to his offspring. It’s the kind of part that risks disaffection, especially given that Schwartzman has always been the most hipster-presenting of Anderson’s main crew, and Anderson toys with that affectation via scenes in the film’s framing device, with Schwartzman also playing an actor struggling to figure out his character. (At one point, he’s told his mannerisms are maybe a bit much!) That open-hearted uncertainty is all over Schwartzman’s movie-within-the-etc. performance: What’s ultimately so touching about Augie is the way he appears to regard so much human interaction like an alien encounter; as a war photographer, he doesn’t need to be Richard Dreyfuss chasing after a spacecraft to lose himself in the world outside his family. Fortunately, he may not need that otherworldly validation to make his way back to them. –JH

11. Sam Shakusky — Jared Gilman, Moonrise Kingdom

It’s messed up how adults find precocity in children to be a cute quality, reducing their exceptional maturity into an infantilizing novelty. The quiet frustration of being an old soul trapped in a pubescent body takes shape in the stone-faced Khaki Scout Sam, ushered into a grown-up world he can only partially comprehend by the death of his parents. His learned self-sufficiency prepares him for a romance of passionate conviction that he demands be taken seriously by the assorted guardians fussing over them. In Anderson’s most magnanimous gesture, he obliges the request in the sensitive and respectful passages of courtship, even as he lingers on the remaining wisps of Sam’s quickly vanishing innocence. –CB

10. Roebuck Wright – Jeffrey Wright, The French Dispatch

In a nod to the journalist’s “telegraphic memory,” Anderson gives space to Roebuck Wright’s time-stopping eloquence; for what feels like a very long time in the madcap third chapter of The French Dispatch, we simply listen as he narrates his experiences as a James Baldwin–esque Black, gay expatriate. An American in France, an exile forever hoping to find a home, Roebuck Wright feels personal to Anderson, who could be described in similar terms, and that affinity allows him to plausibly, movingly imagine a number of other, less familiar things things — about sexual difference, racial prejudice, incarceration, shame — that push his filmography beyond where it usually goes. –MA

9. Mr. Fox — George Clooney, The Fantastic Mr. Fox

Both as a vulpine cat burglar and as a working dad leaning on his family’s patience to pursue his impractical professional aspirations, Mr. Fox gets away with a lot. And so his voice could only be the crinkly baritone of George Clooney, a human dynamo of charisma able to cruise his way back into the good graces of any heterosexual woman with a look and a smile in place of a whistle and click. He’s the archetypal rascal you can’t stay mad at, perhaps the defining quality of the incorrigible Mr. Fox, a guy promising his wife with each new year that this will be the one he gets out of the game before it plays him. And like the Cloonester — then America’s most eligible bachelor, after rising to fame by healing sickly tots on E.R. — he always stops short of using his innate likability for selfish purposes, defaulting to a dependable foundation of good under the caddish exterior easy on the eyes. He’s a man, yes, and very good at making that work to his advantage, but he’s our man. –CB

8. Suzy Bishop — Kara Hayward, Moonrise Kingdom

Is Wes Anderson afraid of women? I don’t think so, not exactly, but there’s certainly something notable about the way so many of his female characters (see above) threaten to puncture the egos of their male counterparts, romantically or otherwise — and how Suzy Bishop, the 12-year-old girl at the center of Moonrise Kingdom’s pre-teen romance, literally punctures the skin of a classmate with some scissors. Naturally, she’s a dream girl for soft-spoken Sam, even if she romanticizes the orphanhood she knows from her favorite novels and he knows from his actual life. Anderson has a lot of young characters (see above!), some of them rowdy, but Suzy’s unruliness has a fierce focus. She knows what she wants, and if it doesn’t immediately bring her peace, it lends her the strength to weather figurative and literal storms. –JH

7. Steve Zissou — Bill Murray, The Life Aquatic

“What would be the scientific purpose of killing it?” “Revenge.” The Anderson oeuvre is not exactly short of ruined sadsacks — and that’s just the characters played by Bill Murray — but Steve Zissou, saggy in his gender-reveal blues and custom sneakers, a kid’s idea of an adult’s uniform, had the furthest to fall. Zissou is a found-family patriarch, an independent artist hounded by bond company killjoys, and an explorer who taps into the deepest realms of childlike marvelment, where bioluminescent marine life glows with an otherworldly animation — and where the grind of everyday life and mortality and responsibility to other people has the hardest time finding you. The songs on the soundtrack, by the alien-obsessed and chameleonic David Bowie, seem to tease Zissou with the false promise of further escapes, with the impossible dream of reinvention; throughout the movie, as he goes through the motions of the work that once gave him so much joy, and intermittently rises to the occasion, the analogy that comes to mind is that he’s sniffing at an ideal of wonder like it’s a jug of milk past its sell-by date — but maybe it’s not curdled? When Steve finally drinks deep, it’s still good after all. “I wonder if it remembers me.” –MA

6. Margot Tenenbaum — Gwyneth Paltrow, The Royal Tenenbaums

There are a lot of Anderson characters who are distinctive-looking enough to pop off the page of a graphic novel or a children’s book, but even by those standards, the Margot Tenenbaum look — bob haircut with barrette; heavy eyeliner; long mink coat; striped dresses; “alteration of glove” — is as immediately distinctive as any number of superhero get-ups. That’s not to take away from Gwyneth Paltrow’s perfectly judged performance as the secretive middle-child adoptee (or, for that matter, from Irina Gorovaia’s equally perfect work as the young version of Margot). But there may not be a better example of an Anderson character who channels pain and doubt into impeccable self-presentation — in other words, what actors, superheroes and angsty teenagers alike all have in common. –JH

5. Herman Blume — Bill Murray, Rushmore

In his birth as an equally mercurial indie fixture, it was Lost in Translation that brought Bill Murray the closest to Oscar glory, and with good cause. But it’s Herman Blume, the wealthy industrialist who befriends ambitious yet academically challenged teenager Max Fischer, who is the true face of a post-zaniness Murray. A deadpan sadsack with flashes of both amusement and rage — he makes the simple admonishment “UNLOCK IT!” into one of the movie’s (one of cinema’s?) most memorable line deliveries — seems in retrospect a perfect stand-in for Murray’s melancholy aloofness. (Let’s think of the likes of Ghostbusters II as the stand-in for whatever business dealings have eaten away at Herman’s soul.) In a culture that assigns rich people a kind of unearned grandeur, it would be easy for Herman to come across as a Poor Old Rich Boy, especially when played by one of the most beloved comic actors of his generation. Instead, Murray allows a festering self-loathing to seep to the surface alongside his self-pity. And for every great line reading, Anderson and Murray provide an indelible image: Herman rampaging through a basketball game, Herman despondently smoking two cigarettes at once, Herman isolating himself at the bottom of a pool, Graduate-style. It’s just as well that he wasn’t even nominated for an Oscar; that award seems too small and fake for this career-best performance. –JH

4. Dignan — Owen Wilson, Bottle Rocket

In The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, there’s a clever if somewhat maddening section toward the end where Huck suddenly has his pal Tom Sawyer at his disposal to aid him in the rescue of his other pal Jim. Tom concocts a plan, but insists on including more theatrical, fanciful embellishments that ultimately only slow them down. There’s a similarly cracked (and, yes, sometimes slightly maddening) Sawyer-ish innocence to Dignan, the wannabe criminal mastermind at the center of Anderson’s first feature — introduced breaking his friend out of a mental hospital where his stay is entirely voluntary. In some respects, Dignan feels almost like a rough draft of Anderson’s later obsessives (and Wilson’s later space-cases), just as Bottle Rocket feels like a looser, less ornate run-through of his pet themes and ideas. No wonder it’s become a worn-out contrarian pick for his best one, actually. It’s not remotely, but sweetly wounded, admirably ambitious, sometimes maddening Dignan may be the most indelible and original variation on Wilson’s singular persona. –JH

3. Gustave H. — Ralph Fiennes, The Grand Budapest Hotel

We count ourselves lucky to meet one person like Gustave H., the plum-suited concierge at Zubrowka’s world-renowned Grand Budapest Hotel, in the course of our lives. An inveterate flirt, overflowing with charm, blessed with the gift of gab, he puts all those around him at ease in a way that only effervescent figments of the screen can. And yet in his jealously guarded imperfections — his private wounds from past harm, his loneliness poignantly symbolized by the threadbare room where he lays his head — he becomes painfully human, an encapsulation of the central tension in all Anderson’s work expertly reconciled by Fiennes, and with every hair in place. –CB

2. Royal Tenenbaum — Gene Hackman, The Royal Tenenbaums

Written expressly for Gene Hackman “against his will” per Anderson himself, the wily patriarch of the Tenenbaum family may be, line for line, the funniest character Anderson and co-writer Owen Wilson have ever come up with, perfectly embodied by one of the great 20th-century actors at the outset of the 21st. Royal is the perfect counterpoint to the quiet melancholy of his precocious children turned emotionally paralyzed adults, and an endless source of a very character-specific batch of “expressions” (well-put, Etheline). So how, exactly, did this shady character manage to sire two gifted sons and adopt an equally gifted daughter, despite his absenteeism, self-centeredness and general status as “kind of a son-of-a-bitch” (well-put, Mr. Sherman)? To some degree, Royal and the movie take this for granted, and of course the movie is largely about him earning back the family’s trust. But even at the outset, there’s something oddly accepting about Royal, even at his most scheming, insensitive or self-serving; his bluntless allows him to cut through his children’s preciousness, at least when he’s paying enough attention to them to do so. There’s also a more subtle familial connection: Though on the surface Royal is one of the least fussy or image-centric of Anderson’s creations, he does maintain a self-consciousness about what kind of story he’s in: “Can’t somebody be a shit their whole life and try to repair the damage? I mean, I think people want to hear that,” he entreats at one point. It’s a tremendously cynical framing of the bad-dad redemption story, and also not incorrect. –JH

1. Max Fischer — Jason Schwartzman, Rushmore

Who else could it be? Rushmore Academy is, of course, St. John’s School, Anderson’s alma mater, where he, like Max, staged plays that kidded the classics and allowed him to assemble his first set of Wes Anderson Players. Anderson honors Max’s aspirations, giving his elaborate plays a sense of scope and ambition that prefigures his own bigger-than-the-real-thing pastiches. (Orson Welles said that Hollywood was the biggest electric train set any boy ever had; Anderson has found it to be the prep school with the biggest endowment.) Max’s attempts at manipulating relationships, and his playacting at grown-up romance, reveal him as an aspiring puppetmaster who hasn’t yet found his true calling in fiction. So many discussions about Anderson, not least this one, circle around the idea of the filmmaker as some kind of Peter Pan, but that doesn’t quite account for the rueful way Anderson takes the measure of Max. He notes how Max’s charming glibness draws real blood; he maps the real scars — of class, of grief — that Max doesn’t even quite realize his school blazer is covering. He thinks it’s his skin, but Anderson, despite his love of dressing up, knows better. Through Max, Anderson came very close to doing something the film acknowledges as impossible: knowing what he knows now, when he was younger. –MA