In recent years, there’s been a lot of debate about museums and universities possessing objects obtained unethically from around the world — whether as the result of imperialism or something else. Unsettlingly, that’s included a host of remains of Indigenous people once held by several American colleges and universities, including Harvard. Recent efforts have sought to redress those historical injustices, with Harvard’s Peabody Museum pledging to return Indigenous hair samples last year.

This practice is, unfortunately, not a new one. And a recent article ventures further back into the nation’s history to find an equally unsettling window into history — one that’s even more disquieting because of how it ended. And it involves the early days of Yale University in the 18th century, at a time when it was still Yale College.

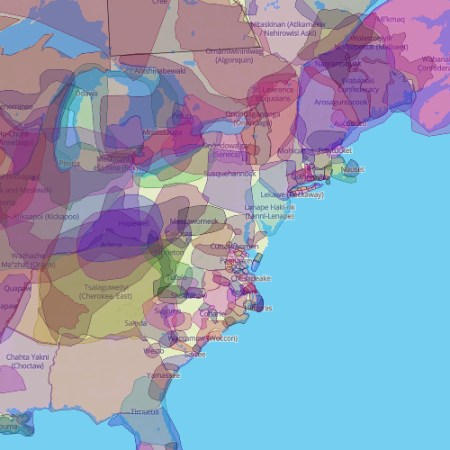

In the article, Matthew Wills describes the legacy of Ezra Stiles, who became the President of Yale in 1778. As Wills describes, Stiles had a penchant for obtaining various artifacts and objects from Indigenous communities in the Northeastern United States and adding them to Yale’s collection — despite what now appear to be sizable ethical lapses in the process.

As Christine DeLuca wrote in a 2018 article for The William & Mary Quarterly, Stiles’s penchant for collecting included the displacement of ritual stones. “When such stones were forcibly wrested from Indigenous sacred landscapes and transported to the college museum or other locales for display before colonial eyes, the very act of collecting caused damage to those objects and their meanings for Algonquians,” DeLuca writes.

Yale’s Controversial Vinland Map Conclusively Revealed as a Forgery

It’s old, yes — just not that oldUnfortunately, the fate of the collection Stiles worked to assemble at Yale is even more frustrating. As Wills recounts, the array of artifacts that he gathered did not remain in the university’s possession after Stiles’ death. As for where the objects he gathered ended up, that question remains lost to history.

Stiles’ historical legacy remains complex. One of Yale’s colleges is named for him, and in 2016, a plaque was placed on the premises honoring three men whose lives were, in various ways, controlled by Stiles. “Two were African American and one was Native American (Western Niantic). One was a slave (he was manumitted), and the others were indentured servants, but none were free,” the plaque reads. “We remember them here.”

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.