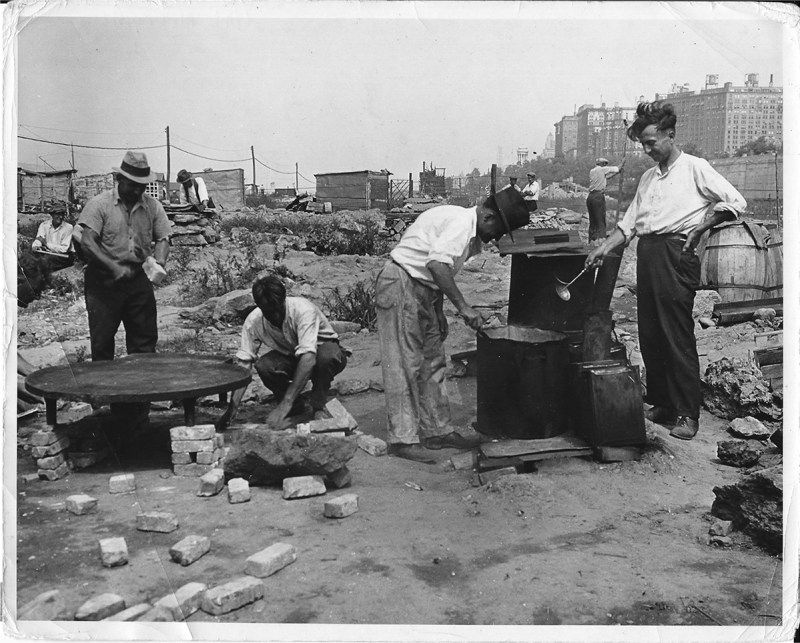

When you learn about the Great Depression in high school, it’s usually about the fallout from the stock market crash of 1929—the lives ruined, the breathtakingly high unemployment numbers, the breadlines.

But you’ll likely never think twice about what was consumed by Americans during the era, because “next to nothing” doesn’t sound so appetizing. Americans still ate though—and there’s a great untold story of their Depression-era diet, which includes such forgotten dishes as lima bean loaf. (Really.)

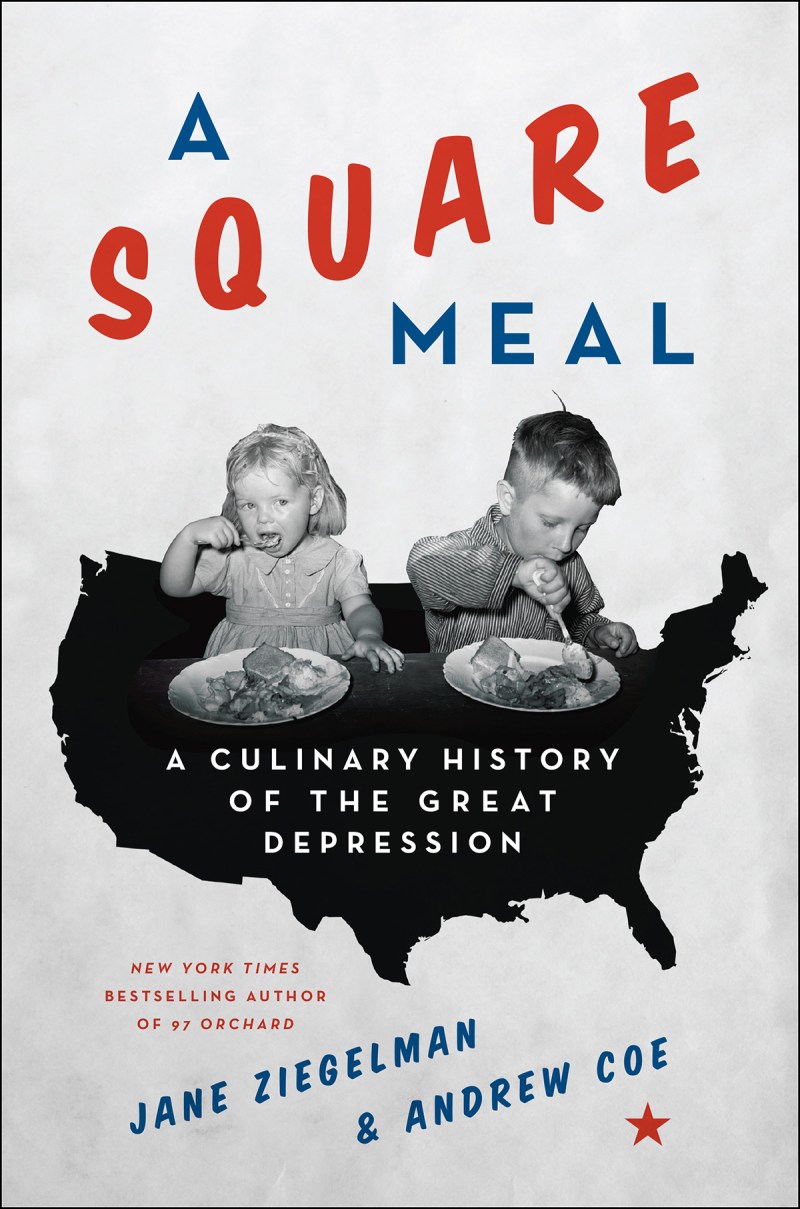

That’s where authors Jane Ziegelman and Andrew Coe, a husband-and-wife team of food historians, come into play. In the couple’s A Square Meal: A Culinary History of the Great Depression, the two talk about the lead-up to the Great Depression, the Great Depression itself, and its aftermath, all through a deeply researched culinary lens.

RealClearLife caught up with the authors at home to discuss their new book.

What drew you to the idea of writing about Depression-era food?

Andrew Coe: We had both written books about food history—I wrote a book about the history of Chinese food in the United States, and my wife wrote a book about Lower East Side immigrant food in New York. When we finished those, we were looking around for another project, and we realized that [the Depression era was] the time when food was one of the most important topics of conversation and on everybody’s mind. Like ‘How are they going to put food on the table, and what kind of food are we going to eat?’

Why was it important for you to tell this story?

AC: One of the reasons is that poverty and hunger…and malnutrition, which became huge topics in the Great Depression, are still with us today. ‘Should we feed the hungry and unemployed?’ or not. And we’re still struggling with what is good nutrition, and what we should eat.

Jane Ziegelman: I just want to add that it’s amazing how little the conversation has changed; the language is almost exactly the same, the questions we ask are the same, and we still don’t have a good way to answer them.

In your book, it’s fascinating that at the time, the notion of what a balanced meal was and what constituted nutrition were trending. Jane, you’ve done some work with the Tenement Museum in New York City. Did your work there help inform this topic?

JZ: In a certain way, it does play in, because the project that I wrote my previous book [on] was in connection with the Tenement Museum. It was looking at families that lived in the building before it was a museum, and I tell their stories using food as a kind of lens. What I realized is that I was really excited by telling the food stories of people that didn’t have a lot. So these are stories in which women were really dependent on their own ingenuity and their own energies to round up food, and get things on the table, and just the way the food economy worked in a really poor neighborhood like the Lower East Side. So in a sense, [A Square Meal] is a kind of extension, because it’s another project about food and wont and poverty. Those stories I find especially compelling.

Have you tested out any of the recipes from the years covered in A Square Meal?

JZ: Yes, we have been cooking dishes for research purposes. We really wanted to know what these foods were all about. I can tell you that they are very different than foods that we eat today. In many ways, [they] don’t have many of the qualities that we’re looking for in food. So you can really see that this is food from another time, which is based on a whole other kind of system of evaluating what tastes good and what tastes not so good.

AC: In short, they are bland and overcooked. [They] kind of have a texture that is uncomfortable in our mouths today.

It’s interesting to read about FDR eating prune pudding to show solidarity with Depression-era Americans. Have you made that recipe?

JZ: Oh yes we have. And it was, I would say, not as bad as it looks. It’s not a pretty dish. But once you get into it, it has some redeeming qualities. Right now, I’m making a lima bean loaf; it’s in the oven as we speak, and it was one of the really commonplace meat replacement foods, so it was something you would bake like a meatloaf and then slice it up and eat it with gravy.

AC: Lots of gravy. Lots of highly seasoned gravy, hopefully.

JZ: We’ve been trying to feed these foods to our children.

Lima bean loaf sounds like a child’s worst nightmare.

AC: It is; they won’t eat it. They don’t understand how and why we’re having these foods on our table.

JZ: I thought this one was OK, actually, next to some dishes that were really truly nauseating. We made a gelatin salad with canned corned beef. It’s not a nice product, and then to put it in a gelatin mold just makes it even stranger. So yeah, the lima bean loaf, I think is a little bit like falafel.

AC: Well, that’s what you think.

Were there moments of clarity or sorrow during the research process? We can imagine writing about these sometimes awful foods people had to eat during this trying era must’ve been quite difficult.

JZ: I would say that reading some of the descriptions of how people were living and what they had to do to get food on the table was really sobering. And this was especially true for some of the people that [my husband] researched. Southern sharecroppers that worked on cotton plantations and whose diet was severely limited. Really, it’s kind of heartbreaking to hear what they considered a full meal.

AC: It was called the “Three M” diet, which was “Meat” (and meat means salt pork), “Meal” (which means cornmeal, so they would make it into cornbread), and “Molasses.” Essentially, you’re eating bacon and cornbread with molasses poured over it for seasoning. And this had a lot of fat in it, of course, and it filled your stomach but it had no nutritional content whatsoever, and people came down with horrendous malnutrition diseases, particularly pellagra, which you could die from. And people were dying during this period. So one of the things for us, which was difficult for writing this book, was that we are food writers, so we write about people eating, and a lot of this book was about people not eating.

In the lead-up to the Depression, America had been fighting World War I, and we were amazed to read in your book how well-fed American soldiers were. That’s an interesting contrast to the reductive lifestyle people were living on the home front to support the cause. That must’ve made the Depression hurt quite differently for each party once it struck. Can you speak to that a bit?

AC: The sad thing about the veterans during World War I [was that] they were fed the most incredible Army rations of any army on earth—they had beef and bread and potatoes; filling, protein-, carbohydrate-rich foods every day, and they lived like kings. And by the time the Great Depression rolls around, these are now men in their 30s and 40s, and maybe things haven’t been going well for them, and they become unemployed, and suddenly, they’re on the breadline, and they don’t have any food, and the government isn’t helping them, and it is a really harsh blow to them. They became part of this movement called the Bonus Army, which tried to force the government to give them food and money and support, and with not very successful results from either Hoover or Roosevelt. Roosevelt was, of course, a bit better, but not great. They were fed after a fashion with him. But Hoover just absolutely refused.

Another really interesting morsel from your book was the breadlines: One, that the breadlines existed prior to the Great Depression; and two, that when you see pictures of breadlines, you don’t see any women on them. It must’ve been twice as hard to be a woman in that era as it was to be a man.

JZ: I think that that’s right for a whole bunch of reasons. I didn’t realize this when I started researching the book, but 25 percent of the labor force was women. So when it was time to lay people off, guess who were laid off first? Women were disproportionately unemployed next to their male counterparts, and they didn’t have the breadlines, for instance, to go to. Breadlines were considered a really distinctly male institution, and they were kind of rough around the edges, and the guys who patronized them maybe didn’t have the most respectable backstories, and to protect your honor and your dignity, you would not fraternize with these people. Add to this the humiliation of putting yourself on a public breadline and essentially telling the world that you’re not only a failure, but [also] that you have no man to take care of you, [and] that was a double-whammy. Women were technically allowed to stand on breadlines, but the force of social convention kept them off [them]. They wouldn’t subject themselves to it. And as a result, they suffered more than their male counterparts.

Food is so indelibly linked to the American experience. Would you say that hunger is just as much?

AC: No! At that time, we had no national conscious or memory of hunger, unlike almost any other country on earth, from China to Western Europe. Western Europe during World War I had huge problems with hunger and starvation, and that wasn’t an American thing. So this was the first time that hunger came to the forefront, and it was a very difficult thing for Americans on every level to deal with. I think for the people of the generation who grew up during the Great Depression, a lot of them were really, really strongly marked by that. It really affected them and affected their behavior through the rest of their lives.

What was the biggest takeaway you had from writing this book? Do you feel spoiled knowing what earlier generations had to deal with?

JZ: Yes, we are incredibly privileged to have the variety and the abundance of food [and] all these fantastic choices in terms of the wide spectrum of immigrant cuisines that have been brought to the United States. All that’s great, but I would say that the book also shows us some of the really fantastic historical local food traditions that have been lost since the Great Depression. Just lost under the kind of steamroller of modern supermarkets and mass production, and these are food traditions that we can no longer sustain in the modern world. I also think in some ways, it was a time when people were really food idealists. They really cared about food, and they really thought food could make the world a better place. Not just feed people, but that adopting the right food policies could make a better American society. Despite the Depression, there was something very hopeful at the bottom of it.

AC: But I think it was also a reminder to us that [even though] we live in this time when there’s incredible food out in the United States…life is precarious, and bad things happen, and this could happen to any of us or to all of us. And so, enjoy it while you can. There’s certainly hungry people still in the United States, but the big difference is that they’re hidden, while during the Great Depression, the breadlines were out in the streets and people [were] saying, ‘Buddy, can you spare a dime for a cup of coffee?’ So we’re not nearly as aware of hunger as people were during the Great Depression.

You can buy A Square Meal here.

—Will Levith, RealClearLife

Every Thursday, our resident experts see to it that you’re up to date on the latest from the world of drinks. Trend reports, bottle reviews, cocktail recipes and more. Sign up for THE SPILL now.