For anyone familiar with the world of action sports, Selema Masekela needs no introduction. The legendary sports commentator was ESPN’s host of both the X Games and Winter X Games for 13 years, has covered both the Olympics and World Cup for NBC Sports, and served as both host and executive producer of VICELAND’s docu-series Vice World of Sports. His voice and visage are inextricably linked with some of the most — if you’ll pardon the expression — “holy shit” sporting moments of the last quarter century.

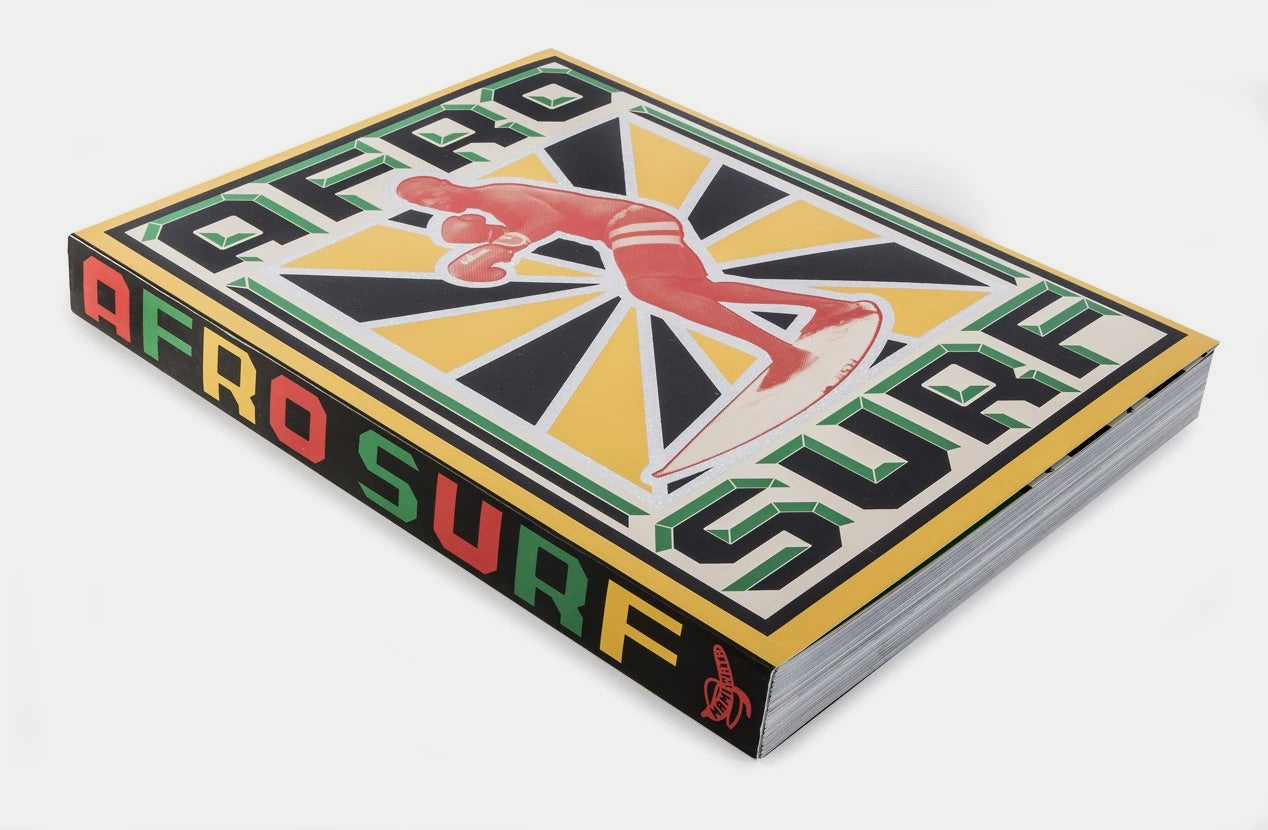

The son of famed South African jazz musician Hugh Masekela (and an accomplished musician in his own right), Selema has also spent a significant portion of his life on the African continent and has of late been hard at work on Afrocentric surf apparel brand Mami Wata. The term “Mami Wata” translates to “Mother Water” (or “Mother Ocean”) and serves as a powerful moniker to invoke the brand’s celebration of African surf culture as well as their mission to create jobs, grow economies and support youth surf therapy organizations on the African continent. In addition to their range of eye-catching tees, hoodies and boardshorts (all designed and produced in South Africa), Mami Wata also supports said organizations via the book AFROSURF, described as “a visual mindbomb packed with over 200 photos, 50 essays, surfer profiles, thought pieces, poems, playlists, photos, illustrations, ephemera, recipes, and a mini comic, all wrapped in design that captures the diversity and character of Africa.” It’s a dope read and we highly recommend picking up a copy.

InsideHook sat down with Selema to discuss the brand, the book, his viewpoint on surf culture and surfing as therapy, memorable moments in his career, and the joys of dancing on Instagram.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

InsideHook: Let’s start with the genesis of the Mami Wata project and your role in it — how did it all come together?

Selema Masekela: So, Nick (Dutton, Mami Wata co-founder) and company in Cape Town, they’ve been working on it since about 2017. I was visiting South Africa, my father was sick with prostate cancer. I was really spending most of my time in South Africa in 2017, going back and forth with him for treatments, etc. I’ve spent a lot of time in South Africa in general, obviously because my family’s there, but it was very intensified around that window.

A friend of mine named Maria McCoy — this dope South African footwear designer who knows how much I love surfing — was like, “Yo, you need to meet these kids in Cape Town, they’re doing something that I think that you will be blown away by.” She connected me, we started talking, and they had made us this short film called Woza that was beautifully, artistically done. It had an indigenous Black South African kid as its protagonist, but it was normal — it wasn’t like, “Oh my gosh, these are Black guys surfing.” It was richly South African, but also digestible for anyone who saw it. So I connected with them and we started talking and really quickly I was like, “Yo, this is dope. I can’t believe that it’s only here. This would be amazing in America.” Shortly thereafter, they brought me on as a co-founder and I just started helping right off the bat, growing the brand.

You’ve been into surfing for a really long time. What was it like to be creating this brand at this stage in your life and career?

It was always a dream for me growing up as a kid, in So-Cal with So-Cal brands — I never saw anything that was reflective of me in the marketing and storytelling of surf culture. And everything that I experienced as far as how people reacted to me as a surfer was very much novelty. This idea that I was some sort of outlier Negro who liked water. People patting me on the back like, “You’re different. You’re more like us, rad.”

It’s interesting to have a passion for a thing like surfing or snowboarding that affects you, and it’s your place to express yourself and to find peace, and also have to constantly be dealing with people looking at you strangely or wanting to comment that you’re even there in the room. Or dealing with the micro and less micro aggressions towards you even being there in the first place. And then nothing to back up your presence in any of the storytelling around the thing that you love the most. So I always dreamt of being able to build a brand that storytold it from another perspective.

I used to draw logos for a thing called Ebony Waves. That was my dream brand. And Ebony Waves didn’t come to pass, but Mami Wata became this opportunity to make Ebony Waves a reality of sorts. And to be able to do so from the depths of my heritage on the largest, most surfable continent on the planet, and African peoples and their relationship with water and the ocean. Gone is this idea of us being outsiders in the space. This is our history.

It’s really been a blast to continue to develop it and to take my experience from my years and years of work in the action-sports industry and work in brand building, and apply it to something like Mami Wata. My father had a song in 1975 called “Mami Wata,” beautiful song. My dad was fascinated with the story of this mother ocean, Mami Wata, this goddess of the ocean. And so to be able to suddenly find yourself in a place like, “Whoa, here I am.” A little over 40 years later, I’m telling that story with different musical notes.

What’s exciting about it is that it’s taking modern African design and graphics and storytelling and applying it to a thing that everyone’s familiar with, which is the ocean and surfing. It just happens to be through an African lens. We in the West have been doing a great job of making our brands appealing and aspirational to people all throughout our country, and we make it so that in other countries, that’s the only way that you can have recognition in the streets is to wear shit that comes from this place that defines your cool, right? I would just say that Africa is entering the chat. You know what I mean? We’re entering the chat, we’re expanding the WhatsApp group, if you will. And the cool thing for the consumer is it’s an opportunity for discovery, for a continued discovery through this lens.

And then just how all of what we make and how we make it and how it’s packaged, etc. is done 100% in South Africa. Made of African cotton and made from raw, sustainable African materials with African creators. And that is something that is an immense source of pride. And that’s never going to change.

Was the AFROSURF book born out of the brand or vice versa?

The book was born out of the brand. We started talking about what a book would look like in late 2018 and our original intentions for how the book was going to be made were much different. It was going to be very much us going place-to-place and shooting it and gathering stories that way. Then COVID happens and the whole world shuts down. And it was like, “Okay, maybe as we all learn how to connect and build connection and utilize our digital spaces for real connection, as opposed to just like, shit, maybe we can quarterback and build this book in community, and do so digitally during this time.” And we all had the time to focus on it.

So we started working on building what the template would look like and then just started reaching out via our relationships with people in Senegal and in Ghana and across the continent — a lot of it through social media, just seeing if people were down and they’d be on board. And the manner in which folks responded was truly incredible.

So it became almost like creation through aggregation.

Creation through collaboration. But a real sort of new form of what the depths of that collaboration could look like. We did a Kickstarter, I shot a video here at my house telling people the story of what the intention for the book was. We put together some imagery and next thing you know, 1,500 people decide to support us in the middle of the weirdest time on earth when no one has any money. People are like, “No, here’s $60. Go make your book.”

We shipped the books from the Kickstarter in December, in holiday of 2020. And then that pass-along started happening. People would have this thing, and now they’re sharing it with friends, and there’s a limited number of copies, and people are like, “Yo, what is that?” Then the phone starts ringing off the hook from actual real book publishers that are like, “This is dope. Do y’all want to do this for real?” It came down to Penguin Random House through Ten Speed Press, and they’ve been incredible partners. Since June I think we’ve moved somewhere around 15,000 books. And the entirety of the profits from this book just continue to fuel what the original Kickstarter was — which was to support these surf therapy organizations on the continent, specifically Waves For Change and Surfers Not Street Children. We felt like we had won just off that first round like, “Oh, cool. Look what we get to support these organizations with.” And now obviously it’s a whole lot more.

It seems like the book and the brand are sort of a celebration of bringing Africa — as you were saying, the largest surfable continent in the world — more to the forefront of the surfing conversation. Are there particular surf destinations in Africa that you feel deserve more shine or awareness?

Outside of South Africa, which is traditionally been known through the white gaze of surfing, and the attractiveness obviously of what Morocco has to offer in the winters, all of the conversation about surfing in those places has been about the waves — not about the people, not about what the culture looks like and feels like there, and how it influences the whole. We give most of the credit in terms of influence — when it comes to the culture — to Southern California, Southern Australia. And I don’t even think we give enough to Hawaii and Polynesia, or even Southeast Asia. We talk about the waves, but those places don’t have as much opportunity to drive the bigger conversation of what the culture looks like, right? The aspirational part, this other lifestyle end of it.

I think that this book really focuses on the people. Why and how the ocean affects people in different places and what their relationship with surfing means to their everyday life relative to where they come from. And then you get to see what the local culture looks like, feels like, tastes like, how you move to it. You’re able to expand the landscape of what the definition of surf culture looks like.

I mean, the first essay in the book is like, “Yo, here’s documented evidence of indigenous Africans surfing in the late 1600s all the way through the 1700s and mid 1800s. Sorry, not trying to change history, but also, like, let’s add that to the mix of our storytelling. Which is very jarring for people for some reason. Like, “Oh, you people are always trying to rewrite history.” No, we’re just trying to share the history that we’ve been deprived of. The world’s a better place when we know various pathways of how we’ve gotten here.

So I love the idea of people putting on their shred destination bucket list, going to scour the coast of Africa for surf. But also to engage with its people and learn about its culture and to do so in Mozambique and in Liberia or Nigeria, Angola. To discover the magic of Africa. Of these 54 countries — without them, the world is a much, much, much different place on so many levels. But most people’s conversation, or even definition or sphere of how they think about Africa is like, “I want to go on a safari one day. Or maybe climb Kilimanjaro.”

And I think what I love about the book is the way people respond, like, “Yo, I had no idea that Africa was so dope.” [laughs] You know what I mean? Because they think of it strictly from a Discovery Channel perspective. And it’s modern, it’s vibrant, and it has so much, as far as its history and its culture, to share and influence the world with.

And then there’s this connection to the mission of these surf therapy organizations in Africa. I’m interested in your personal experience in that regard, in the idea of surfing as therapy. It seems like surfing is a very good conduit to improving your life in so many ways.

Yeah. For me, as a teenager, it for sure saved my life. When I think of the things that I was struggling with and the angst that I was carrying, and identity shit that I was trying to figure out, family stuff, etc., it was the one place where I could go and just be so … even. The idea that what was taking place on land was just completely not relevant. It’s also this dance between joy and survival. And relationship — you have to build relationship with the ocean, and by building relationship with the ocean, you in turn build new relationship with yourself.

And to see the way that idea has worked in surf therapy. If you look at Surfers Not Street Children taking kids who are young — eight, nine, ten, eleven years old — who are living in the streets and engaged in things that no child should be forced to because of various circumstances that are affecting them socioeconomically. Taking these kids, putting them in the ocean and watching them be transformed. Like who they are and suddenly having a why that informs where and what they would like to be when no one has believed in them and they’ve had a difficult time comprehending love and connection. These are all things that surfing can give. With Waves For Change, taking communities and helping them build relationship with the ocean, and then the manner in which it affects the overall connectivity of the community and these neighborhoods in which crime goes down. Working with people who have experienced all different types of trauma and being able to shed that trauma from something as simple as learning to feel comfort and safety and freedom in the ocean.

We’re just trying to share the history that we’ve been deprived of. The world’s a better place when we know various pathways of how we’ve gotten here.

You see the manner in which it affects people who are dealing with all different types of things they carry, things that make life different. I’ve gotten to participate in some of the surf therapy work with autistic folk. People who don’t have the ability to express themselves in the way we’re familiar with. People with the frustration of living in a world where the rest of the world can’t comprehend you and you have to have a difficult time comprehending it and therefore act out in ways that people are scared of. And then you see a kid enter the water and just whoosh … gone. You see them at peace, smiling and laughing in a way that their parents are crying and beyond themselves because it’s not something that they get to see with their kids at home. You’re seeing it with so many organizations, with Life Rolls On and people with spinal cord injury and who just feel like in life they would never would have the opportunity to be that free. To see someone who’s a paraplegic or quadriplegic learning how to ride waves and navigate them, and just their whole life, whole perspective on existence change. So, yeah, I think the ocean is so much more than recreational. And without it, we’re not here.

What do you think it is about riding waves that makes it so universally therapeutic? Is it just that baseline connection with nature that you can physically feel and then try to fall in sync with, or …?

I believe it’s deeper than physical. I think it’s deeply spiritual. I think it’s deeply spiritual, on a different frequency. I went to church three times a week from the time that I was five years old. And when I stood up on a surfboard for the first time when I was almost 17, that was the first time that I felt a connection to whatever God might be. That was the most spiritual experience that I have had to date. And it completely changed the trajectory and direction of my life. Like I got out of the water, I moved five degrees this way, and I went here when I was going to be here and eventually I was out of frame and on a new plane. I think that’s what it does. And I think each person receives that and connects with it — with whatever their energetic frequency is — differently. It brings people peace. If you’re struggling, if you come from a life of struggle, unsurety, identity … the stories are always the same. People are like, “Yo, this is where I come for peace.”

And I feel like everyone’s been dealing with some degree of struggle over the past two years.

And to your point, more people have entered the ocean in these last two years during the pandemic than at any other time in modern society that we can remember. People literally streaking to the ocean and taking on surfing for the first time and taking on snowboarding and hiking and camping and kayaking. Like really making an effort to connect to the earth and charge up and find that peace in the thing that many of them sort of mocked before, right? They were like, “Oh, that’s not, for me. I’m busy being successful, etc., etc.” And suddenly those reasons for existence that they thought mattered no longer exist, and it’s like, “Ahhhh, what do I have now??” So that’s what it’s doing for people who are successful. Imagine what it does for people whose struggles are far more acute and real and more life and death.

Do you feel as though surf culture as a whole is moving toward a more accepting and welcoming place with new people trying to get into it? I feel as though traditionally it’s been a bit like, “Stay off my wave, kook.”

That element is still very much alive, especially here in Southern California. There was such a deep backlash, like, “I can’t believe all these people are doing my thing now.”

“I can’t believe Jonah Hill is surfing.”

Exactly. Those are people for whom the convenience of being able to do the thing and being raised to think that it’s theirs … the stuff that you and I are talking about is hard for them to digest that that’s what surfing is. Because for them, it’s far more competitive and far more a way to make a name for themselves. If you’re a really good surfer in your town, it dictates the way people treat you on land. You get to do some peacocking that comes from that.

And now this is another end of surfing that doesn’t have anything to do with that. It’s just people coming in and being like, “I fell 10 times. I had the greatest time ever.” As opposed to like, “Oh, look at that kook.” It’s different. So it’ll be interesting to see what it looks like five years from now. But I do think it’s going to change. I’m bolstered by the amount of places that are willing to have more conversations about inclusivity.

The people that I see doing work to go out and essentially give access to the gospel of surfing to people who didn’t even know that they had it. I love seeing what the Gudauskas brothers are doing with Positive Vibe Warriors, and City Surf Project in San Francisco is amazing. These kids grew up in SF and grew up in Oakland, grew up in the city, they go and paddle out and they’re like, “Yo, am I in Hawaii? I’m at home??” Didn’t even know that it was something that they had access to, and that changes your life.

Shifting gears, you’ve called some of the most iconic moments in the history of action sports. Is there one or two that still stand out in your mind? Like where the “holy shit” hasn’t worn off?

Man. There are so, so, so, so many. I mean, fuck, obviously Tony Hawk’s 900 is the one. I mean, I was standing on the ramp. I was right there. I don’t think we’d be having these types of conversations we are today or action sports would be something that continues to influence pop culture and global culture the way it does, if it wasn’t for that moment. That transcended the entire planet. And I got to be there for that and participate in storytelling that.

And then the Travis Pastrana double backflip. That was the greatest energetic night of any sports moment I’ve ever participated in. That was some quantum physics-type shit.

You guys rightfully lost your fucking minds a little bit on the broadcast. That clip is so amazing, there’s just so much energy and joy coming out of it.

Yeah, and I think what you don’t understand if you weren’t in the room is that in the moments leading up to that, it was 18,000 people in the Staples Center in some form of collective prayer that this person wasn’t gonna die.

I just remember the mood that entire day of competition and knowing it was leading up to that, there was just an air. The air was thick with what was to come and you couldn’t hide from it. Shit was serious. It was real. I remember seeing his mom in the tunnel before I went out there and she was just standing in the corner, like in tears. And I was like, “FUCK.” Then just looking around that audience of people holding hands … I believe that the collective energy in that room was a part of that being able to take place. We were all one network, connected. That was some beta Metaverse shit that took place.

Ok last question, before I let you go: I have to say your dancing posts on Instagram are some of the most joy-inducing things I’ve ever seen in a hot minute. Do you have any music recos for the people out there who might want to incorporate a little movement into their own morning routines?

A little joy movement?

Yeah.

You know, I never planned on doing the videos. I dance in my house and listen to music a lot, and then suddenly something will happen and I just break the camera out and it’s on. Presently, I definitely recommend the Silk Sonic record — that Anderson Paak, Bruno Mars shit is just like … if you need joy in your life, just listen to that album loud. If you’re not dancing and feeling good from those records, that’s when there might be something really, really wrong with you. Yeah, you’re in the sunken place.

But I mean, for me, it could be anything in this house. I could be doing that to Wu-Tang. I could be doing that to Depeche Mode. I could be doing that to Jay-Z. I could be listening to Brazilian classics. I’m a weirdo. My dad always used to say, “There’s only 12 notes. It’s all music.” It’s also a great way to learn about people, listening to stories from musicians in places that aren’t necessarily your jam. I have a weird secret thing with Miranda Lambert.

Not so secret anymore!

People would probably be like, “Whoa, this dude’s at home, vibing out, screaming at the top of his lungs to Miranda Lambert.” Yes. Yes. That is a thing. In fact, I think that’s one of my videos. Yeah, I do have a Miranda Lambert video up in my reels.

People are constantly telling me that I’m blowing it because I’m not on TikTok. They’re like, [funny bro voice] “Duuude, if you were on TikTok, you don’t even know hard you’d kill ‘em.” But I don’t know.

They’re not wrong.

[laughs] I know, it just feels like another thing. But the thing I do see when I look at TikTok videos, it’s like the last place and it has its dark entity. But it is that last place where people don’t have to try to be something. Where people are celebrated just for where they are and who they are in the moment. And I hope that’s what social media as a whole could be the driving force for. For that collective possibility and the manners in which you see sameness in people that you’re maybe not necessarily “supposed to.” I think that’s what I enjoy about those moments. I feel like I’m doing something that anyone else might be doing in their house and maybe people might just be surprised. That’s how I get down. But I’m also a dork and I enjoy making people laugh.

It’s infectious. I would honestly go a step further and say, “Put a record on, force yourself to dance and tell me that you don’t feel better 30 seconds into it.”

Yeah. You just hit the nail on the head. New choices lead to radically new outcomes. And sometimes it’s little choices that lead to radical new outcomes. And sometimes it’s as simple as putting a song on and dancing. And you could feel like complete shit and be hopeless, and you know, two, three minutes later it’ll be like, “Holy shit. I’m back. I’m here.”

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.