This is the fourth volume of a weeklong series on the theme of fatherhood in the work of six contemporary filmmakers. You can read the rest here.

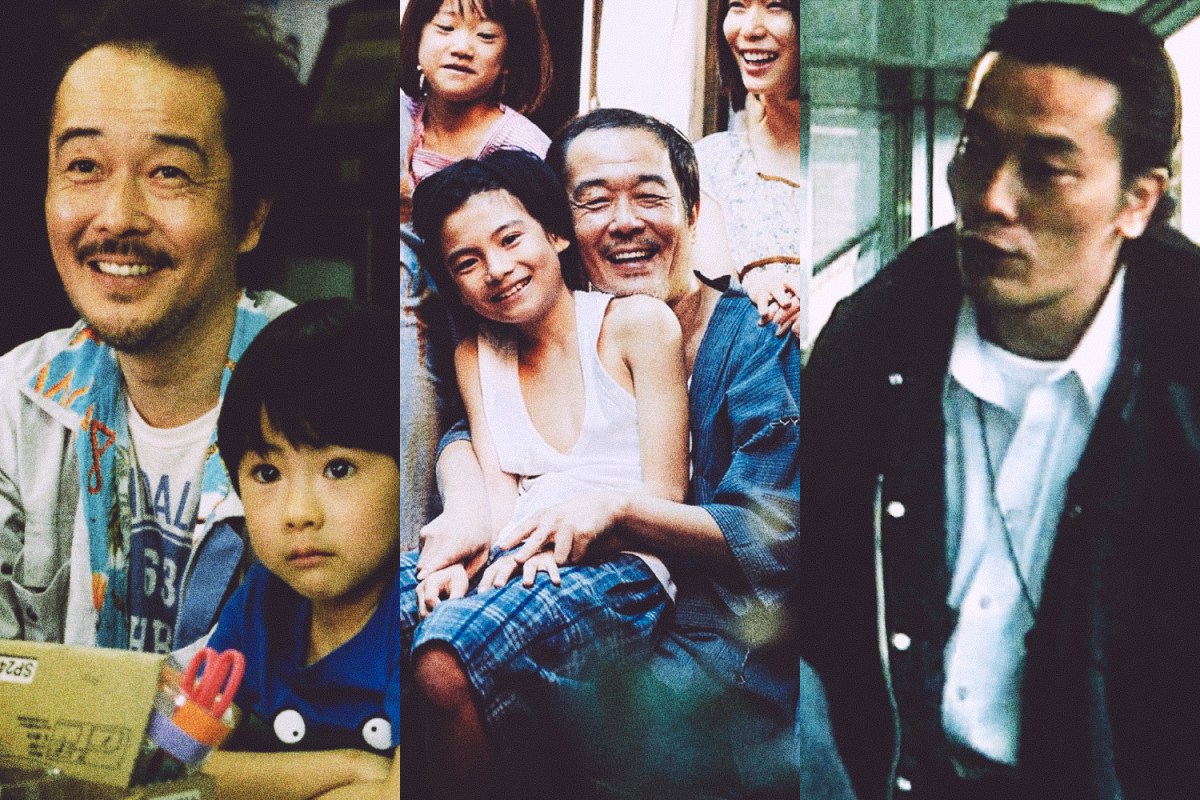

Before we can talk about the fathers in the Japanese writer-director Hirokazu Kore-eda’s films, we have to talk about one of his mothers, the slyly domineering Toshiko Yokoyama, played by Kirin Kiki in 2008’s Still Walking. There’s a dad in Still Walking as well: Kyohei Yokoyama, played by Yoshio Harada. And he too is a piece of work, passive-aggressively making sure his children know how disappointed he’s been in their choices. But it’s Kiki’s sweet-faced Toshiko who has really raised manipulation to a high art form, by pampering her kids with food and special gifts while simultaneously delivering devastating insults.

Still Walking is a vivid drama in a middle-class milieu, filled with rich characters who have such tight emotional bonds with each other that they start to suffocate at the slightest pull. The movie marks something of an endpoint for Kore-eda when it comes to telling stories about families; for much of the first two decades of his career, he explored how social obligations and cultural expectations confined parents and their children. Then, his focus shifted.

What changed? For one thing, he became a dad. Around the time of his 2013 film Like Father, Like Son — the film of his most overtly about fatherhood — he spoke frankly to the press about his worries that his career was keeping him away from his daughter too much in her formative years.

Japan also began to change during what would turn out to be a tumultuous decade for the country. The collapse of the global economy, coupled with devastating natural disasters, effectively led to a realignment of cultural values. Kore-eda has spoken about this in interviews as well, saying he’s been inspired post-2008 by stories about his compatriots who’ve been rethinking their lives while just barely scraping by.

Like Father, Like Son cuts to the heart of the matter. The premise is pretty sensationalistic, as an upper-middle-class family and a family living on the edge of poverty discover that a hospital mix-up has led to each of them raising one of the other’s children. But just when it seems like Kore-eda’s going to drive this story straight into melodrama — with the stuffy rich father plotting to get the courts to award him both sons — the movie veers off in a different direction and becomes more of a low-key character study, exploring what it takes to be a good father.

In one corner, there’s Ryōta Nonomiya (Masaharu Fukuyama), an overworked architect who’s convinced himself that although he barely spends any time at home, his distance is helping his son become more independent. In the other, Yūdai Saiki (Lily Franky), who’d rather loaf than work, but who also makes every day a fun adventure for his kids. While Kore-eda doesn’t exactly give his blessings to Yūdai’s lifestyle, he does indulge in a bit of fatherly fantasy, imagining what it would be like to have all the time in the world to be a dad.

It’s an idea he’d played with a bit in his previous movie, 2011’s I Wish, in which two brothers separated by divorce go on a road trip with their friends as part of a plan to bring their parents back together. One of the film’s subtler observations is that only one of the boys is excited about the reconciliation. The other one likes living alone with his father, an indie-rocker who lets him eat late-night snacks. Just because parents may not be “good providers,” that doesn’t necessarily make them unfit.

Kore-eda started out making documentaries, and released his first fiction feature, Maborosi, in 1995. In many of his films — both before and after Like Father, Like Son — parents are defined as much by their absence as their presence. In 2004’s Nobody Knows, a group of kids have to fend for themselves for months when their mother abandons them in search of better economic opportunities. In 2015’s Our Little Sister, three young women meet their half-sister, who knew their long-estranged father better than they ever did.

Lately, Kore-eda has put those absentee fathers at the center of the story. In 2016’s After the Storm and 2017’s The Third Murder, the protagonists are pretty shaky dads. The former is a gambling-addicted writer and part-time private detective who has trouble paying child support and is danger of losing his son to his ex’s new boyfriend. The latter is an attorney who often only sees his daughter when she gets into trouble. The two men end up in different places before the end credits, with the writer coming through for his kid in a crisis and the lawyer left so shaken by an especially grim homicide case that he wonders if humanity itself has been a mistake. But Kore-eda clearly feels for them both.

Like two of his key influences, Yasujiro Ozu and Mikio Naruse, Kore-eda has long been interested in the in the myriad ways that family dynamics can be warped by perceived slights and miscommunicated expectations. He’s highly attuned to the casual cruelties of traditional families, where people can share a pleasant afternoon tea while also pecking away at each other.

What’s changed since Still Walking is where Kore-eda’s sympathies lie. He still cares about how children are affected by their moms and dads, but he also seems to understand the parents.

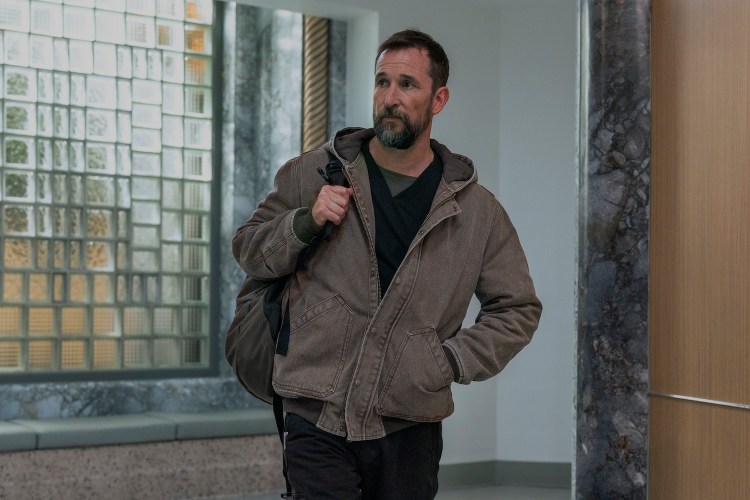

Ten years after Still Walking, he made Shoplifters, a film in some ways its mirror-image while also informed by a decade of Kore-eda movies about slacker dads. Like Father, Like Son’s Lily Franky returns as a similarly big-hearted small-time thief named Osamu, who helps take care of a cluttered house full of kids and adults alongside his partner Noboyu (Sakura Ando). But while the multiple generations in Still Walking gather out of blood obligation, nobody in Shoplifters is officially related to each other. This is a home full of foundlings and people bound by a combination of circumstance and convenience, and they’re all making it work, pooling their meager resources and sharing each other’s pains and joys.

Shoplifters won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, where Kore-eda had competed multiple times before winning the top prize. (Like Father, Like Son did receive a special Jury Prize.) It’s arguably his fullest film, combining his usual domestic melodrama with elements of mystery, all in service of story about a collection of marginalized misfits who seem generally more compassionate and emotionally stable than the “respectable” families in his other movies. It’s only when the authorities show up in Shoplifters and reframe Osamu’s life as one of self-serving grift that his “take what you can get” ethos becomes suspect. That climactic switcheroo sets up a powerhouse ending.

There are several strong contenders for the title of “Kore-eda’s best,” including 1998’s After Life, the film that firmly established him as one of his generation’s finest filmmakers. After Life isn’t directly about what it means to be a dad, or even to have one. But it is about what it means to be alive, and it shares with Kore-eda’s “family” movies a fascination with the bric-a-brac that humans accumulate and then leave behind.

In After Life, the newly dead decide what scene from their lives they want to inhabit for eternity. In Still Walking, a pair of sometimes exhaustingly demanding parents honor their family’s history and quietly express their love for their offspring via the piles of books and clothes they’ve never tossed out. In Like Father, Like Son, an overworked father misses his son the most when he looks at the boy’s scattered toys and photos. In After the Storm, a part-time dad hopes to stay in his son’s life by buying him some baseball gear.

If there’s one big idea about fatherhood that recurs throughout Kore-eda’s work, it’s that what matters the most is just being there: as much of a constant and a comforting part of a child’s daily life as a poster on a bedroom wall. And for those who can’t, or maybe won’t? Sometimes, the best that all fathers can hope for is to leave some tangible proof that, if only for a little while, they were around.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.