This is the darkest time of year to be a runner, literally and figuratively.

There is a special communion, though, in encountering other cold-weather runners and exchanging a knowing wave. It means far more than the “Hey, we bought the same car!” wave. A runner’s wave (or interchangeably, a runner’s chin nod) is a quick, agreeable conclusion that you don’t know each other, you will probably never know each other, and yet you are of the same tribe.

You’re both putting in icy miles, windy miles, no-sun miles — whether or not you’re training for any race in particular — because running routines don’t go into hibernation. They find a way.

It’s an admirable pursuit…which is also built on some compelling science. Cold-weather miles have a real capacity to supercharge a runner’s physical and mental fitness, making us fitter, leaner and meaner for the full year of running ahead. We dive into the benefits of the practice below.

How to Use Running to Unlock Your Kindest Self

Done right, the pastime rewards patience and cultivates perspectiveIt’s Science

For starters, let’s debunk the myth that running in the cold “burns more calories” than normal running. Running longer distances, or running them through six feet of snow in Russian backroads a la Rocky IV, burns more calories than normal running.

That said, there have been scientific studies that prove cold-weather running helps improve performance. A team of sports scientists at St. Mary’s University in London had test subjects run 10Ks in two different “environmental chambers” — one a summer chamber, the other a winter chamber. The team showed that heart rates are 6% higher in hotter conditions (blood floods to the surface of the skin during extensive sweating, which taxes the heart) and due to poor thermal regulation, runners are 38% more dehydrated. (Meanwhile, when you’re cold your blood flows to the core, which tricks the body into thinking it has enough fluids.)

In other words: running’s just blatantly harder in the summer. So, cold-weather running can help you set a personal best (if you’re so inclined; while that doesn’t have to be the point, as we’ll touch on in a bit), it should at least encourage you to come back out for more sessions, which in turn will really improve performance.

“Cold Sculpting”

A few years back, we spoke with Dr. Robert Zembroski about “Scottish showers,” the practice of taking ice-cold rinses in order to energize the body and stimulate the immune system.

One potential benefit of the routine is a process called “cold sculpting,” which suggests that cold-temperature exposure can help turn white fat (the inflammatory fat linked to heart disease) to brown fat (naturally occurring fat that produces heat). Running outside over the winter could catalyze this conversion, which will in turn burn off the excessive white fat. The science is young, so don’t bet the house on an Olympic body by St. Patrick’s Day, but the signs are there that combining consistent exercise amidst cold temperatures will help your waistline.

(Below) Zero Expectations

A simple joy of cold-weather running? People who’ve never tried it don’t expect to like it/feel good during it/run fast. This rightfully strips running of its greatest obstacle: the menacing mental hurdle. It’s better to get out there and expect little, than to not get out there at all. Look at it as a non-qualifying headstart to your spring get-into-shape plan. Eventually, spring will arrive…and you’ll already be in shape.

Review: This Merino Wool Puffer Is the Best Jacket We’ve Ever Run In

Enough with the layering. Ibex’s best-selling jacket is all you need.For the Never-Treadmillers

The knock on treadmills is more spiritual than scientific. Most runners know that treadmills don’t alter your gait or wreck your knees. Running on rubber instead of concrete, and cutting wind out of the picture entirely, is actually less taxing on the body. But for those who can’t stand them nonetheless, who long for that discovery component of a run — cold-weather running is your calling card.

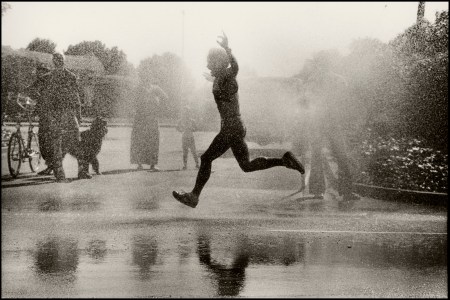

The Solitude

Finally, the cold-weather run comes with a heavy dose of solitude. It’s a free tech detox, a chance to check in with oneself, an opportunity to cash in on the little sunlight available to us during the darkest portion of the year, and a proven challenger to seasonal affective disorder. Maine-based writer Caitlin Shetterly summed up the feeling beautifully in a piece for The New York Times:

” … When I am running, I find a room of my own. In the wind and bright sun, in the cracking ice echoing through the salt marsh, in the flight of the blue heron up above, in the scratch of my ratty running shoes on the sandy, icy shoulder of the road, I am free. And mostly alone, as few runners join me on the slippery roads of winter … When I am running there is nothing but time and my own body and however long it will take me to get there. Everything else needs to wait. And believe me, sometimes it does take a long time. I am that slow.”

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.