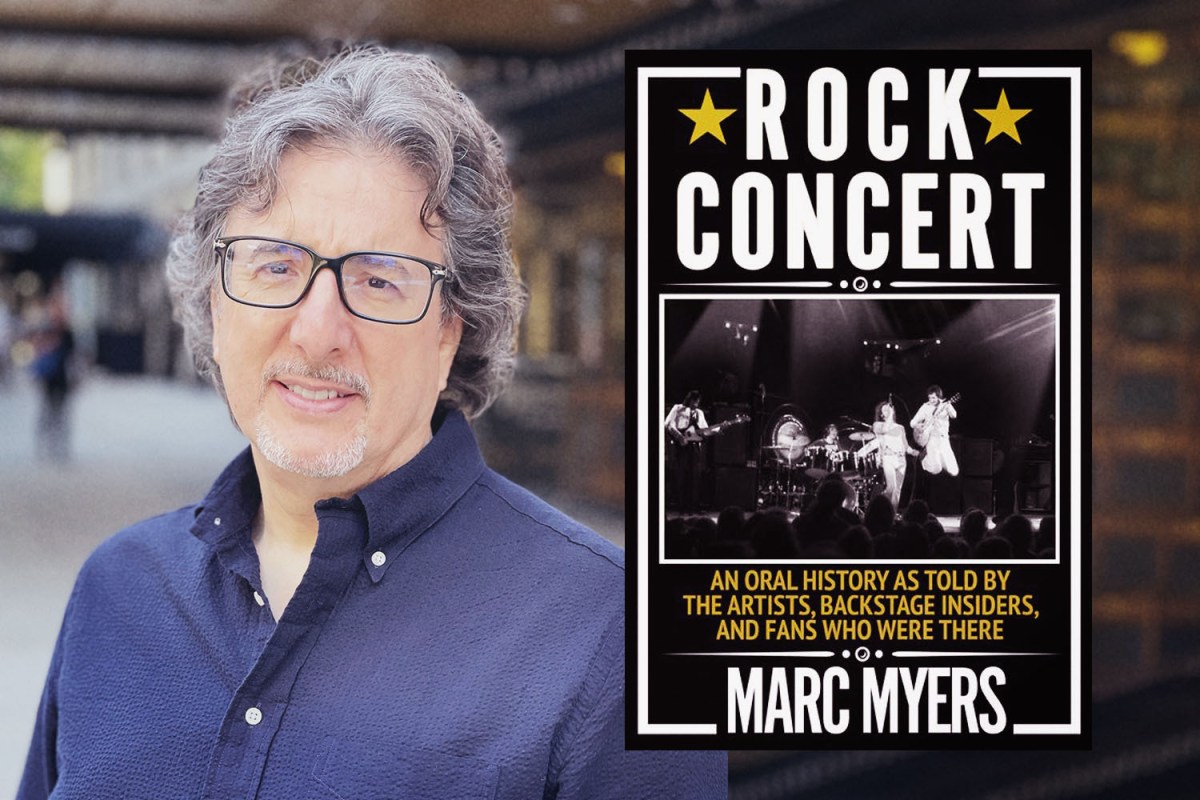

Aptly titled Rock Concert, Marc Myers’s latest book takes on what the author calls “the cultural phenomenon and the rite of passage” of the rock concert we’ve come to know — and love. In Myers’s cinematic construction, the book examines the development of the arena rock show through an oral history that spans from the late 1940s to the mid 1980s. We get insights not just from beloved rock and roll icons like Ronnie Spector (may she rest), Joan Baez, Alice Cooper and Angus Young, but from people behind the scenes, who photographed, lit, assembled and created soundscapes for acts and shows that became among the biggest in the world. In this incredibly engaging narrative, we also learn the impact politics, civil rights, economics and technology had on the rock concert’s evolution and sustainability.

Myers, who has been assembling oral histories for both his own books and his columns at The Wall Street Journal, was drawn to the idea after interviewing photographer Bob Willoughby. While Willoughby has become known for his images of classic jazz and Hollywood celebrities, Myers was especially entranced by the photographer’s images of saxophonist Big Jay McNeely performing to screaming crowds at Los Angeles’s Olympic Auditorium in 1951. “I interviewed him and he talked at length about the excitement, the smell of the place, the sound of this auditorium that was used for boxing and professional wrestling. I thought, that was 1951, how does something so funky, expressive and intense go from that to a multibillion dollar industry?” Myers said. “That’s where the curiosity explosion happened. I wanted to know why and how that happened over time.”

Here, Myers talks with InsideHook about the importance of countercultural history, The Beatles, Chuck Berry and, of course, his first concert.

InsideHook: What was your first concert?

It was October 1971 and I saw Santana at the Felt Forum at Madison Square Garden. The opening act was Booker T. and Priscilla. I was like 14 and I went with my best friend. The lights came up and the band went on and everybody got on their seats, jumping on them like trampolines. That was excitement back then. The joy or electricity of that first concert was that there were no adults, no parents. Everybody in my row, who I could see, was dressed the same way–aviators and workshirts, held together with safety pins if they were torn. Nobody was getting beat up by jocks.

Back in the prehistoric era when parents hated the music, you went into a concert a child and you came out a young adult because…should I smoke that thing that person just passed me? Hey, that girl looks cute, she’s smiling at me, maybe I should talk to her? There were experiences you had at the concert that you needed to make up your own mind about. When you came out you suddenly felt empowered, that you knew better, that you could push back when your parents said you couldn’t stay out late, you should study harder, you should be a lawyer at your father’s lawfirm. The concert was a unifying experience. Concerts have always been unifying experiences, dating back 3000 years BC. The live performance was always a way to get everybody who may have had different viewpoints to come into a space and see everything the same way.

One of the things that’s interesting is that the book chronicles, albeit indirectly, the birth of the teenager.

Correct. You’re pointing out something that was fascinating to me as well, which is that before 1955, the music industry did not care about young people at all. Recorded music was an adult diversion. Kids couldn’t afford that stuff, they didn’t have any discretionary income. There was no such thing as the suburbs then or working for money you could keep as a kid. It’s not until ‘55 that suddenly this industry realizes animated djs all over the country are connecting with teens, that a teenage market holds enormous financial potential. Suddenly not only does the music industry goes after teens but artists start creating music that speaks directly to their angst. It’s about cars, lousy teachers in schools, getting pushed around by parents. It’s all themes that had never really surfaced before.

How did you decide what these three decades of oral history would include and exclude?

I don’t like books that bore me to tears or tell me what I already know, books that are dry. Because I’m a historian, I was less interested in what and who and more interested in why. Why comes from many perspectives. It’s not just the rata-tat-tat of this happened on this date and that date. I’m much more interested in social history and those side events that apply pressure to make change. I was fascinated by all the people around the periphery, the ring of movers and shakers who weren’t in the limelight. I wanted an emotional history in this book, witnesses who were emotional about what they saw and the roles that they play. There are stories that never would have come out if I went to the obvious sources.

You say rock and roll and the words that accompany that are sex and drugs. I really didn’t want to get into that because it was a cliche. You can see that in films, endless books have been written about it. I’m not interested in what’s already baked into the rock concert, what we already know of rock and roll. What I was looking for in my book was, who built the rock concert and how did it change over time? I was very interested in external forces and how this thing evolves from something so small and sweaty to something so big and slick.

How do you think the history of the rock concert affects the way we interact with music now?

I think the history of the rock concert is like the history of the Harley or the history of jeans, the history of anything that’s culturally or counterculturally important. It gives us a roadmap. I learned a long time ago that when you do something compact and exciting, it becomes read. When you do something exhaustive, you create exhaustion. My job here was to provide a framework of how this thing evolved, not only its rise, but how it twists and turns. Why do the Beatles happen when they do? Why does Chuck Berry resonate when he does? How did Live Aid get put on? It’s a granular, emotional history of something that is fundamental and essential to the culture from 1950 to 1985. Just hearing the words rock concert, rock star, it immediately says excitement. It means that this music you see today has a history and that people sacrificed a great deal to make live music possible the way it is. The youth culture has something to do with it, just the feeling that kids had when they heard rock and roll, how they suddenly felt empowered both as consumers and individuals. Because kids at one point in this country weren’t individuals. They were people rushing through childhood to get to adulthood, told to shut up because nobody cared what they thought. It was in part because of live music that young people were suddenly able to wrest control of their lives away from adults.

Why were you interested in oral history for this book specifically?

With this book and when I write oral history in general, I’m really writing a screenplay. It’s a movie, that’s why they’re so visual. I always like a big, loud opening, I always like a poetic end, and I always like turning points. There are stories within stories that are part of a larger arc. For me, oral history is selfless. What I mean by that is, if people think they had conversations with the subjects themselves, if I disappear, I did my job. I’m very conscious of how things need to be arranged and need to unfold, but it’s not about me. I want the reader to have an intimate relationship with the subject. It shouldn’t sound like they spoke to me and I distilled it and now it’s mine. I want you to hear what these voices sound like, what these people felt, how they delivered their ideas. Oral history is the fastest way to do that cinematically. It comes from my desire to have you have my experience, to have a great time and see everything cinematically like I do. As a writer I need to set myself apart, every writer does. You have to create your way of doing things and it becomes your signature.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.