Peter Beard’s 40th birthday was at Studio 54. “An elephant cake,” ridiculously, “descended from the ceiling.” His 65th birthday was at the VIP Room Club in Paris. Models everywhere; he kissed Claudia Schiffer’s cheek. But this year’s festivities, on January 22, were relatively subdued.

“Celebrating being 82 years with Nej, Zara and man’s best friend at Land’s End,” observed his Instagram account, ticking off the names of his wife and daughter. Beard, appearing attenuated but alert, sat at home, surrounded by a bird’s nest of magazines, newspapers and works of art. The great photographer, who famously traversed the world, stared at the dog, whose name was Finnegan, sitting regally to his left.

After that Wednesday, Beard’s comings and goings are harder to document. What is known for sure is that, 69 days later, on March 31 around 4:40 p.m., the gray-haired man with blue eyes — absurdly piercing in the famous author photo — was seen, reported the local paper, “wearing a blue pullover fleece, black jogging pants and blue sneakers.”

Then he was gone.

He vanished from Montauk, an East Hampton hamlet on the far end of Long Island. It’s a town to which Beard would return again and again after a half-century of international adventures.

He’d gone for one more walk, and when his body was finally found, it turned out he hadn’t strayed far.

Beard, born in 1938, always had homes elsewhere — Hog Ranch in Kenya, of course, and there’s still an apartment in Manhattan’s West 50s. But he seemed, in his dotage, to love the property in Montauk most of all. He began visiting as a kid, with his father. The six acres he personally inhabited, perched on a cliff overlooking the Atlantic, were purchased in 1972 for $135,000. He’d been a big deal for years by then, and well-known around town. “The handsome Peter likes Caroline [Kennedy] just fine,” gossiped Igor Cassini, “but the natives out in Montauk, L.I. know that he is the constant houseguest in that resort with Princess Lee Radziwill and sister Jackie Onassis.”

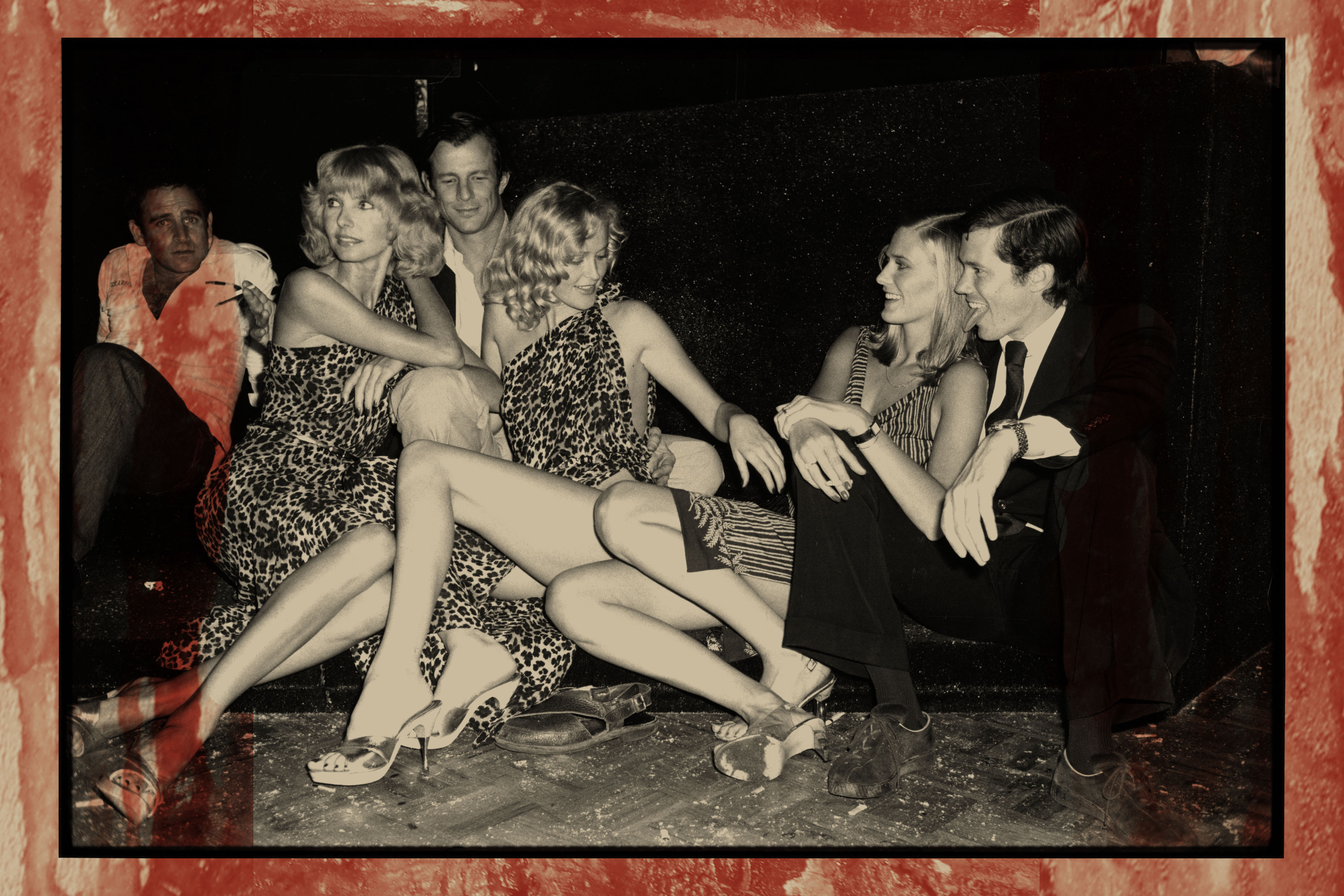

Montauk’s population was sparse (East Hampton’s year-round population didn’t exceed 2,000), but nevertheless Beard had illustrious company: Andy Warhol lived a mile walk away, Dick Cavett bought a Stanford White home in 1968 and Edward Albee wrote some of his greatest work from a sun-drenched second-floor study at 320 Old Montauk Highway.

Cavett met Beard on a cliff. He found the man’s way of life exhilarating in small doses, but also exhausting. “I thought some of the things I’d heard about him had to be exaggerations,” Cavett tells InsideHook, “but I don’t think any of them were.”

The next year, 1973, Beard — a man of “intense eccentricity,” as Michael M. Thomas recently put it — bought a windmill, too, toting it eight and a half miles home. Strange as it was, the purchase was in character for a man attuned to nature and its slow degradation.

And that’s where he lived, happily, for a while.

***

By the time he settled in Montauk, P.B., as Beard was often known, had been famous for at least a decade.

“There’s a new glamor boy on the horizon,” reported the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1963. “He’s not just a handsome lady’s man, but an accomplished actor, author … and photographer.”

Indeed, there was already buzz about The End of the Game, his landmark book on African wildlife to be published two years later, and his naked appearance in Jonas and Adolfas Mekas’s Hallelujah the Hills!, in which he streaked through the Vermont snow. Barely pausing for breath, he purchased 45 acres in Nairobi (1965), participated in a study on pachydermata (1966), shot the cover of a LIFE magazine feature on elephants (1967) and was arrested for assaulting a poacher (1969).

The old Montauk — the one that Beard then arrived at, to develop what would become his lifelong estate — is gone. What it once was is, frankly, hard to imagine. It is conflated, unfortunately, with the glitz and celebrity nearby. “The Hamptons suggest a kind of milieu, not always correctly,” says Anthony Haden-Guest, the aristocratic writer who wrote the introduction to one of Beard’s books. “When I came, it was very different. It was very people-sleeping-on-sofas-and-tracking-sand-into-each-other’s-houses.”

John Flanagan, a longtime restaurant owner, met Beard in the early 1980s. He remembers Montauk as a sleepy place: “The average person out there would go up to Montauk once a year,” perhaps for lobsters. “The motels were all half-falling apart. There was no reason to be there.”

“It was so remote, and interesting, and it was raw. It wasn’t fancy, by any stretch,” says Vincent Fremont, who worked for Warhol and lived on the property owned by the artist and Paul Morrissey, who directed Trash, Flesh and Heat. Fremont remembers a population of fishermen and, in the summers, middle-class families. “No one followed you past Amagansett, so you had this privacy. Most people didn’t want to go that far.”

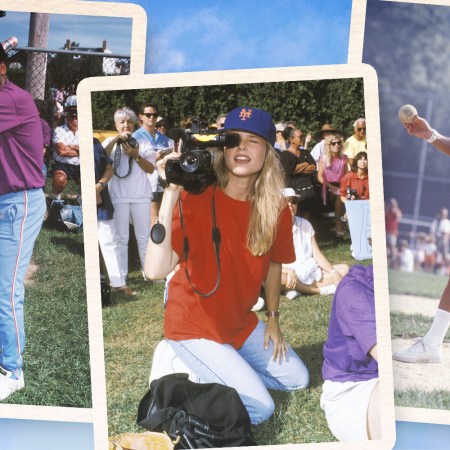

In 1974, Barbara Allen trekked to Montauk to meet Beard. She was an assistant to Warhol, and a model, photographer and journalist. She fell for Beard despite his recent high-profile attachments to Radziwill and Candice Bergen. (The New York Times gingerly referred to Allen as Beard’s “current girlfriend.”) Warhol’s compound was occupied by The Rolling Stones. One night, at 3 a.m., a guest of Beard’s awoke to rattling. It was Mick Jagger climbing through the window, looking for Allen.

“It was so out there, isolated. It was nice to get out of town,” Allen says. She loved it. Beard would pick her up in a station wagon and drive her to the Island. A decade or so later she married Henryk de Kwiatkowski, who made millions in used airplanes. But in the moment, on that quiet cliff, she slept in the windmill and found it to be roomy.

“The sleeping quarters were all around.”

But always, there was the art; it was easy to forget sometimes, with Beard so often acting more like a playboy than a man with a keen sense for lighting and composition.

Beard’s debut one-man show, The End of the Game, ran at the International Center of Photography from 1977 to 1978. Visitors absorbed more than 300 photographs, films and sketches. There was also the first of his massive collages, and a “60 foot elephant herd print wrapping the entire building.”

He found a kindred spirit in Bruce Weber, a young photographer. Weber remembers meeting Beard in the early 1970s, when he was finishing up at New York University Film School. They both did print work at Lexington Labs, in Manhattan. Weber admired Beard’s curiosity about animal life and Africa.

One day, Weber asked Beard, “Where are you hanging out? Where are you living these days?” “Out in the car,” Beard replied, “in front of the lab.” He’d sleep there at night before going to a friend’s apartment to shower and brush his teeth.

Weber found tremendous success working for Ralph Lauren and Calvin Klein, and would, like Cavett, eventually buy a Stanford White-designed house (the group of Montauk homes bearing his mark are nicknamed the Seven Sisters). But well before that, he’d come to Montauk when Beard, who had gone with the Rolling Stones on a two-month concert tour, returned from the road. Rolling Stone had paired him with Truman Capote to capture the goings-on.

Weber stayed at the Morrissey-Warhol compound. Sometimes Beard would stop by, often in the company of a beautiful woman. “Bruce, can I come in for just a few minutes? This girl is dying to see your dogs,” he once said. Of course, the woman didn’t like dogs, and wouldn’t let them touch her. “I was like a stopping-off point for Peter. He’d go from house to house. He was like that Burt Lancaster character in The Swimmer.”

Beard became famous for his own open-door policy, and his friends would come and go as they pleased for many years.

***

In July 1977, Beard’s home was consumed by flames. “A salvaged windmill known as the easternmost house on Long Island burned to the ground in Montauk on Wednesday night in a spectacular fire that flashed through the framed cliffside dwelling,” reported the New York Times. Thousands of photographs, gone. Scrapbooks, gone. Bacons, Warhols, Picassos — gone.

Years later, Beard walked around the property with Christina Strassfield, who curated his last major show. He seemed, to Strassfield, not terribly broken up by the memory. “He was a person who always looked forward. It’s something that happened,” she recalls. “I think other people might’ve been devastated by it, but I think he just moved on.”

Or, as his friend John Flanagan put it: “Time moved forward, and he moved with it.”

Contemporaneously, however, a spokesman told the Times that Beard was “particularly distressed” by the loss of his scrapbook diaries, which chronicled 20 years of his life.

A few months later, Beard ran into Andy Warhol at Studio 54. In his diary, Warhol wrote:

“He told me he was glad after the Montauk fire burned his mill-house down that he wouldn’t be doing diaries anymore, that he was actually relieved they’d all been destroyed. I told him not to be relieved, that he had to do more.”

***

Beard, by all accounts, never treated his celebrity like a finite resource. He wasn’t precious about it. “I don’t even know if he thought he was famous,” says Maury Hopson, a hairdresser to the stars who met Beard in the late 1970s.

Jason Behan knew Beard since he was a kid, because his father owned Shagwong, one of the photographer’s favorite restaurants. “He was always down to earth,” recalls Behan, who was three decades younger than Beard. “Even once my friends and I became of age, and we were drinking and hanging out with him, he was always very friendly.”

Shagwong’s bartender, Colin “Hollywood” Pyne, agreed. P.B. treated him well, and was a generous tipper. He wasn’t necessarily predictable, however. “Hey, Hollywood, I’m coming out with five people,” he’d say. “Make sure I’ve got a table for six.”

“Okay P.B., what time you coming?”

“I’m not sure.”

“So you had to have a table waiting for him,” says Pyne, chuckling.

***

Beard first married in 1967, to Minnie Cushing. She’d been an assistant to Oscar de la Renta. The wedding was in Newport, Rhode Island. De la Renta himself designed the bride’s gown. After the ceremony, the newlyweds stood on a cliff. “When the water comes in, let’s jump off,” said the groom. “In our wedding clothes?” said the bride. “Yeah.” They stood on the edge. One. Two. Three. The bride jumped, and landed in the water. The groom stood above, smiling and waving. Years later, she told a friend that it typified the short marriage: Most of the time, you were by yourself.

In 1982, Beard married Cheryl Tiegs, a supermodel. The union lasted four years. It was the third marriage, to Nejma Khanum in 1986, that stuck, and produced a child. (Beard sent friends an announcement of the birth; it contained drawings and the infant’s footprint.) Not that it wasn’t contentious at times: she reportedly had him commited to a psych ward and limited his access to money. Friends contested, and still do, that she ended the open-door policy. But she also recovered artworks he’d given away. She buffed his reputation as his work fell out of favor. One could argue, in fact, that she kept him from bankruptcy. She almost certainly prolonged his life.

Beard spent much of the early 1990s away from Montauk, at Hog Ranch in Nairobi. But P.B. kept his toe in the town’s affairs. In late 1992, a group of locals, suspecting that Montauk’s 2,000 residents were shortchanged by not being incorporated, launched a campaign to secede from East Hampton. Beard, a member of the committee, believed the move would help preserve the town’s character. He said, according to the Daily News, that Montauk has “no sense in architectural planning,” and cited a video-game store and new condominiums. “And yet they torture our citizens who want to add on to their homes by making them wait years for building permits.”

Leslie Bennetts, a writer for Vanity Fair, had crossed paths with Beard during her summers in the Hamptons. She was assigned a profile ahead of the first major Beard retrospective, at Paris’s Centre Internationale de Photographie, in November 1996. He was estranged from Nejma and their daughter. Beard seemed eager for the profile; it was Bennetts’s impression that his reputation as an artist was in eclipse.

Bennetts flew to Nairobi to meet him. She was with him for days, from sunup to sundown. The resulting feature would cement his legend as “Half Tarzan, half Byron,” as “an internationally known photographer who has contempt for photography,” as “a rakishly handsome playboy,” as “an enthusiastic drug user who always seems to have a joint lit (unless there are magic mushrooms or cocaine available).” She captured a scene of Ethiopian girls exiting Beard’s tent. Bennetts also adeptly, and notably, documented her subject’s environmental prescience:

Beard is forever spouting dire warnings and apocalyptic predictions about the fate of a doomed planet. It is a vision he has always expressed most hauntingly with his work, an extremely eccentric oeuvre that transcends every genre and resembles nothing outside of its creator’s fervidly bizarre imagination.

“Peter was a free spirit and always chafed at any restrictions,” she says.

As the piece was in its final stages, Beard was gored by an elephant. She punctured his thigh and, as Beard’s official website puts it, “crushed his ribs and pelvis with her forehead.” Upon arrival at Nairobi Hospital, he was suffering from internal injuries. “As he was wheeled into the operating theater,” Bennetts wrote, “he had no pulse.”

The reporter found him in his hospital bed, recovering, being fed sushi by a model.

Bennetts found Beard friendly and interesting. But also, she says, “totally feckless,” and willing to use his innate charm and good looks for sometimes dubious ends. Claiming to be broke, he left her with bar and restaurant tabs. (“I think at one point he tried to get me to pay for his car.”) She finally had to tell him, yes, she worked for Vanity Fair, but no, she — a mother of two kids with no trust fund — would not cover his living expenses. “You were always kind of torn between the charm and letting him off the hook, or letting him get away with something. And finally there comes a point with people like that where you always have to draw a line in the sand and not just not let yourself be taken advantage of or abused.”

I wondered if Beard just didn’t know how the other half lived. Or did he not care?

“He didn’t care. He couldn’t care less.”

The last decades of Peter Beard’s life were productive, but the work slowed from the frenetic pace of the early years. In 2004, he published Zara’s Tales. Named after his daughter, it’s a collection of his adventure stories. He continued to travel, visiting Egypt and Turkey. The End of the Game — the book that catapulted him into the zeitgeist — was republished by Taschen. Then, in 2013, he suffered a stroke.

In the summer of 2016, Guild Hall, an East Hampton museum, staged a Beard retrospective. Strassfield, the curator, had approached him about a show. As with the Vanity Fair profile, Beard was eager.

It was his first solo exhibition in more than a decade. Last Word from Paradise featured drawings, diaries and collages from Kenya and Montauk. Museumgoers got a first look at photos Beard had taken of Jagger, Onassis and Warhol.

As he and Strassfield walked through the show, he told her about the different pieces. She could see his passion for Africa and his zeal for preservation. He talked about Montauk and the erosion of the land. “He felt that that was some of the most important work that he had done,” she said. “It really meant the world to him.”

The show was one of the best attended in the history of the museum. Friends from all walks of life showed up. Local shop owners and fishermen mingled with art-world elite.

And Beard was there to greet everyone.

***

In his last few years, Beard’s friends didn’t see him often. He developed dementia. Friends could no longer come and go, and some resented it.

Maury Hopson went to a recent Rolling Stones concert with Beard and his daughter. They were guests of Keith Richards, and spent time with the band before the show. “I think he’d had some falls and broken bones and stuff, but he didn’t appear to be invalid at all.”

John Flanagan spied him getting out of a car in front of Soho House in Manhattan. “He had just gotten out of the hospital a few weeks beforehand,” he says. “And he seemed to be just completely fine.”

Vincent Fremont and his wife visited Beard and Nejma a year and a half ago on a chilly fall day. “We spent the afternoon with him in his house, watching him cutting and pasting, and doing his art like we always used to,” he says. “He seemed good, but definitely physically more weakened.” Fremont thinks that’s probably why friends didn’t see Beard much; Nejma was simply trying to protect him.

Of course, he observed, “It’s very difficult to stop Peter from doing what he wants to do.”

Jason Behan, the owner of Shagwong, saw him last at a birthday party. He seemed older, of course, but “he was raring to go and everyone else was trying to tell him he had to go home.”

Bruce Weber ran into Beard last summer in Southampton, after a movie. “He seemed good.”

Anthony Haden-Guest saw him a few months ago, at dinner on the Upper East Side. “I knew he wasn’t well,” he said, “but when I last saw him, he was fine.”

***

When Beard disappeared, some of his friends thought it was a joke. It was, after all, on the cusp of April Fool’s Day. And, as they all said, he’d played such pranks in the past. “I’m sure that he went down and got on the boat and he’s up in the Vineyard, for God’s sakes,” one told InsideHook last week.

Still, I could tell they weren’t optimistic. They’d lapse into the past tense only to apologize. One said there’d been a high tide the night he disappeared and there was no fence separating the property from the edge of the cliff.

On April 19, after an extensive search by police, K-9 units and helicopters, the news came: a body had been found in Camp Hero State Park, which abuts Beard’s property.

At the conclusion of Zara’s Tales, Beard had written:

The faster and farther we go from nature, the more we seem to lose: not just crocodiles and elephants, but the whole diversity package. The intertwined, symbiotic complexities of the wild-deer-ness, whose fitness and uniqueness enable survival, just can’t ever be repeated.

Here he was at the end, close to home, and intertwined with nature.

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.