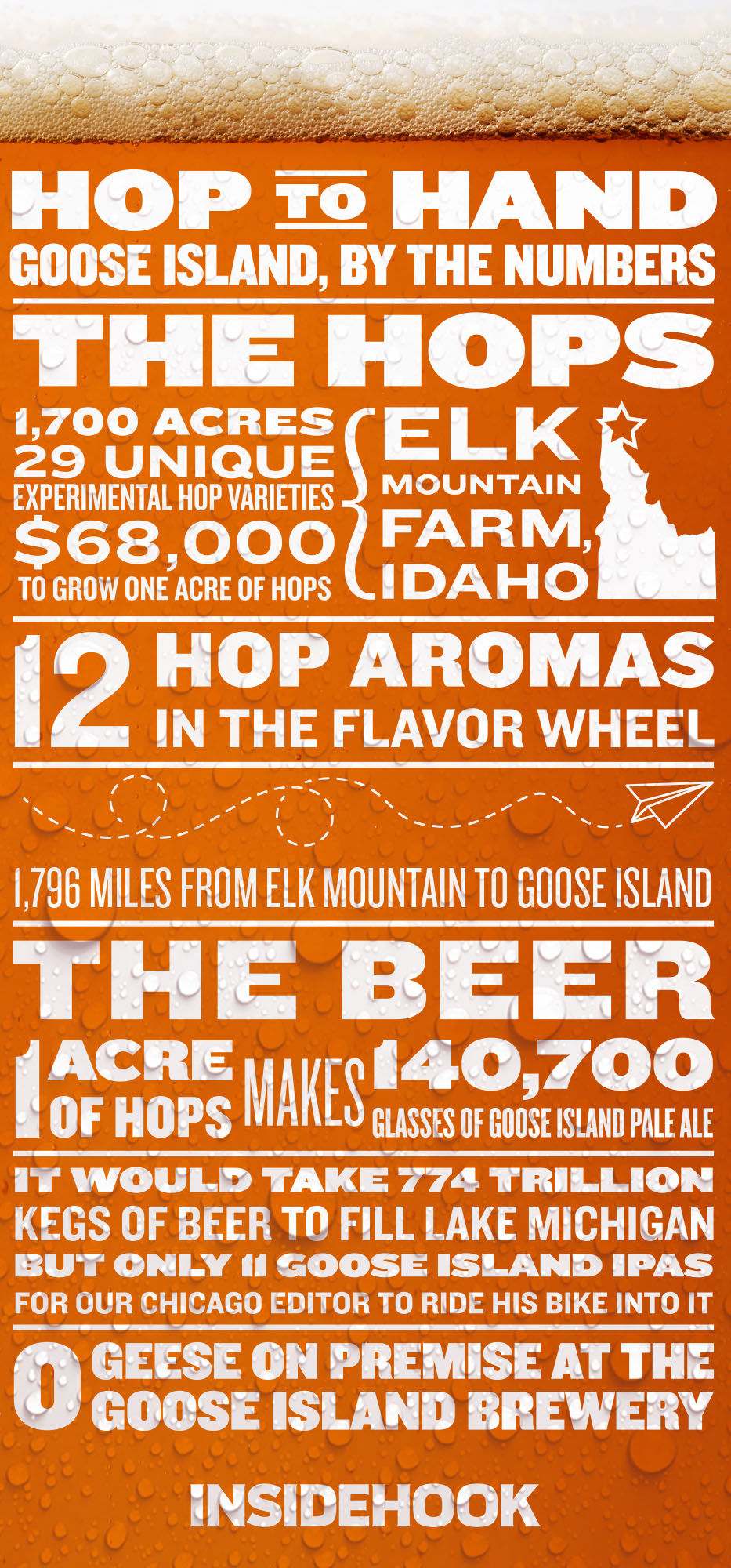

Earlier this month, we traveled to Bonners Ferry, Idaho, to learn where Goose Island sources its hops. Elk Mountain Farm is a gorgeous place, and located on the 49th parallel, which, geographically, puts it in line with Munich and some of Europe’s most famed growing regions.

We came. We saw. We drank. Kinda’ like Lewis and Clark. But with fewer buffalo, more elk and a whole lotta hops.

We also chatted with Elk Mountain’s man-in-charge, Ed Atkins, to find out exactly what it takes to run a succesful hop-growing operation. Here’s what we found.

Ed Atkins says that hops are one of the most unique crops a man can grow. I believe him.

He also says the 1,700 acres of arable Idaho topsoil we’re standing on are not for everyone: “You either love it, or you leave it.”

That bit is harder to believe.

Elk Mountain Farm sits in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, at the tip-top of the Idaho panhandle, in a town called Bonners Ferry. Population: 2,500 and change. The Canadian border, they tell me, is only “10 miles north as the crow flies.”

It’s easy to wax romantic at a place like Elk Mountain. But the reality is that the agricultural side of beer is one of skill and industry, back-breaking labor and prodigious precision.

This is the house Anheuser-Busch built. It’s the largest contiguous parcel of land dedicated to growing hops in the entire world. And Atkins — a fourth-generation farmer, his voice laconic, his diction matter-of-fact — has been here from the beginning: 1987.

Almost three decades later, he’s running the place.

The beer industry, of course, has changed. Immeasurably. Elk Mountain is now the breeding ground of Goose Island, who went major in 2011 and are now giving the farm new meaning in the everchanging world of craft beer.

What are hops? One quarter of beer. The other three are water, yeast and barley. Hops are why you love, say, the distinct bright spicy notes of an IPA versus the subdued, malty flavor of a bitter English ale. Without hops there is no brew. And without Atkins and his team, there are no hops.

Hops are also very fickle.